Building a Bridge

For the Catholic Church to respect the rights of LGBT people would require upending the sexuality stigma and gender hierarchy on which it is built. The outside of the Vatican. (Aanjhan Ranganathan / CC 2.0)

The outside of the Vatican. (Aanjhan Ranganathan / CC 2.0)

The outside of the Vatican. (Aanjhan Ranganathan / CC 2.0)

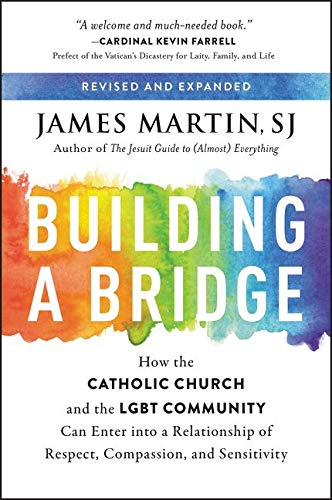

“Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter Into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity” A book by James Martin To see long excerpts from “Building a Bridge” at Google Books, click here.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, I developed the impression that churches were usually centers of social justice. Of course some religious groups have opposed efforts for integration and equality. But as a kid I didn’t know that. I thought all preachers were like the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and all parishioners were protesters. Then I grew up. Now, as a lesbian and an activist for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights, I have encountered religious organizations that stand in staunch opposition to justice for all. The Catholic Church was — and remains — a prime example.

James Martin wants to change all that. Martin is a Jesuit priest and writer who has spent years providing spiritual counsel to LGBT Catholics. In June 2016, when a shooter killed 49 people and wounded dozens of others in a gay nightclub in Orlando, Martin was surprised that few Catholic leaders spoke out against the attack and the underlying hatred of the gay community. In response, he posted a video on his Facebook page calling for a new and improved relationship between the Catholic Church and the LGBT community. The video went viral and is the basis for Martin’s new book, “Building a Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter Into a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity.”

As a secular Jewish lesbian, I found Martin’s book to be a lovely glimpse at church-community relations buttressed by an enlightening collection of uplifting scripture. The problem is that Martin doesn’t adequately address the deep ecclesiastical and theological roots of the Catholic Church’s anti-gay antagonism. And so his book reads like a solution to a problem he fundamentally misunderstands.

I appreciate that Martin means well. He wants the Catholic Church to literally practice what it preaches and apply the teachings and philosophy of Jesus to everyone in its flock, including LGBT people. Martin calls for “more understanding and conversation between LGBT Catholics and the institutional church,” which he analogizes as a “two-way bridge.” For Martin, the building blocks of that bridge are “respect, compassion, and sensitivity” — to be shown by the church toward the LGBT community and vice versa.

Those values of “respect, compassion, and sensitivity,” which guide the form and structure of Martin’s book, come directly from the Catechism of the Catholic Church. But Martin negates the rest of the passage in the 1992 Catechism, which refers to “men and women who have deep-seated homosexual tendencies.” The Catechism continues: “This inclination, which is objectively disordered, constitutes for most of them a trial.”

Martin notes the contradiction only in glossing over it, making the excuse that the church’s homophobic language “relates to the orientation, not the person” — a difference without distinction to most LGBT people as well as those who take their hateful cues from the church text. But either way, when the church asserts that gay people should be treated with respect, compassion and sensitivity, it’s plainly not a statement based in equality and thus dignity, but rather disorder and thus pity. In grounding his book this way, Martin inadvertently reminds us about the church’s deep-seated prejudices and undermines his entire point.

Certainly much has changed for the better, as Martin capably illustrates. “Some bishops have already called for the church to set aside the phrase ‘objectively disordered,'” and “Pope Francis and several of his cardinals and bishops can use the word gay, as they have done several times during his papacy.” That’s all well and good. Martin says the church should use respectful language and suggests that it should welcome LGBT people because we’re fun, which is true. We are. But what about supporting the full inclusion and equal dignity of healthy, happy, sexually active LGBT Catholics? Is that a bridge too far?

Here’s where Martin gets caught. In preposterously suggesting that the historically maligned and marginalized LGBT community should meet the Catholic Church halfway on this metaphorical bridge of respect, compassion and sensitivity, he argues that “in the institutional church, the hierarchy operates from the position of power” and therefore “LGBT Catholics are called to treat those in power with ‘respect, compassion, and sensitivity.'”

Within the Catholic Church, that hierarchy is exclusively male. Not out of habit but by design; the hierarchy of the church gives more power and authority to men. No matter how devout they are, women cannot become leaders in the Catholic hierarchy. This is institutional misogyny that reinforces and rationalizes misogyny in society as a whole, a misogyny that also manifests in the enforced gender codes and norms underlying sexism and homophobia.

The same is true for the privileging of celibacy within the church. Except in parts of Latin America, the Catholic Church hierarchy is celibate — which implicitly suggests that holiness and sexuality are at odds with each other. Is it any wonder that the Catholic Church remains one of the most dominant forces fighting even the most basic forms of contraception access in rich and poor nations around the globe? Cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin writes about the “charmed circle” of sexuality, where a few types of sex and sexuality are accepted while everything else is to varying degrees condemned. Sex for procreation between monogamous heterosexual married couples is accepted by our society, as it is by the church. It’s easy to map the church’s institutional hierarchy on top of society’s sexual hierarchy. It’s also easy to see how the church’s shaming of anything outside that hierarchical charmed circle seeds shame in society more broadly.

At a fundamental level, the Catholic Church perpetually associates sexuality with sin in ways that make stigmatizing any non-normative sexuality all the more likely. Of course, that stigma has been dealt in some directions more than others. The church remains more vocal in its condemnation of women who have had abortions than of the men protected within its own institutional hierarchy who have perpetrated the sexual abuse of children. Indeed, in a book ostensibly about sexuality and the church, only once that I noticed did Martin mention the sex abuse scandals — and that was in the context of pleading with LGBT Catholics to find compassion for the bishops who have to “deal with the fallout” from such cases. But I found it hard not to think about the priest sex abuse cases and the implicit hypocrisy underlying Martin’s text. To paraphrase Jesus, let those who are not objectively disordered cast the first stone.

Beyond the most superficial gestures and rhetoric of respect, compassion and sensitivity, Martin doesn’t address the sorts of lives he envisions for LGBT Catholics. Should they be celibate? Not marry? Exactly how welcome does Martin think they should be? Absent these details, Martin risks promising merely the illusion of equal dignity. LGBT Catholics don’t just want the lip service of respect; they want actual equal treatment. Either Martin doesn’t know the difference or he’s unwilling to do more than dip his toe into the subject.

Of course if the Catholic Church treated the LGBT community with even superficial respect, compassion and sensitivity, that would be a big step — and make a significant impact on the lives of LGBT Catholics whose family members have been taught by the church to hate them and who have been taught to hate themselves. But for the church to truly respect LGBT people and their rights would require upending the sex and gender hierarchy on which the Catholic Church is largely built, a hierarchy it seems to cling to even more fiercely the more it seems antiquated in the society around it.

In fact, Martin may realize this. He ends his book with a series of biblical passages for study and, finally, a prayer of his own creation — offered for the comfort of LGBT Catholics and those who love them. “So please, God, help me remember my own goodness, which lies in you,” Martin writes. That inadvertently points to the futility of his quest — and suggests that in addressing the problems the institutional church has caused in their lives, LGBT people must bypass the church and look directly to God.

Sally Kohn is a writer and a CNN political commentator.

©2017 Washington Post Book World

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.