Borrowing While Poor

Why should a poor borrower be held more responsible than a rich borrower for the default of another poor borrower?

Congress is in the midst of investigating why Alan Greenspan and the Federal Reserve did not prevent the subprime fiasco, and now the SEC is suing Goldman Sachs for fraud. But neither the investigation nor the suit addresses the most repugnant aspect of subprime lending, which is the fact that poor people are charged higher interest rates than rich people when they purchase homes, and that this is perfectly legal.

The justification that economists give for this is that the poor have a higher risk of default and must therefore pay a premium for presenting this higher risk. But it is not the borrower who is in default who pays this premium; it is the other borrowers — the ones who do not default — who pay the premium and thus cover the losses caused by the ones who do. Why should a poor borrower be held more responsible than a rich borrower for the default of another poor borrower?

This discrimination against homebuyers based on income is produced by market competition. A rich family is less likely to default, so in order to attract such families lenders offer them a lower interest rate. But someone has to pay to cover the losses from bad loans, and if rich families are given a way not to pay for these losses, then poor families end up getting stuck with the bill. While the motivation for this discrimination may be totally innocent, the result is that it frees rich families from what should be a shared responsibility, shifting it all to the poor.

Although income discrimination is similar in some ways to racial discrimination, the remedies must be radically different. Under anti-racial-discrimination laws, a lender is not guilty of discrimination if her decision not to lend to a particular individual is motivated by economic considerations. But while it’s legitimate to use the level of a borrower’s income to determine whether that borrower is creditworthy, it should not determine the level of the interest rate she is charged.

If income discrimination is to end, a law that requires banks to offer the same interest rate to all homebuyers, regardless of income, will not suffice. Under such a law, some banks would announce a low interest rate that would be offered to all, but their loan qualification criteria would exclude the poor. Other banks would probably offer a high interest rate to all, but because of the high rate their only customers would be the poor. Each bank would not discriminate, but all the banks collectively would. To solve the problem, the government should establish the criterion for borrowers’ qualifications, requiring that banks offer the same interest rate to any borrower who meets this criterion.

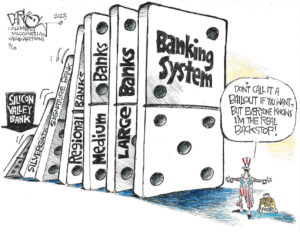

Of course, some would complain that such regulation would be an unwarranted expansion of government in the marketplace. But as the bailout of the banks and other financial institutions clearly showed, the loan market does not consist only of private arrangements; individual loan failures and the way they are covered have social consequences that affect all of us. When homebuyers pay back their own loans, they also pay for the losses caused by other homebuyers who are not paying back theirs. Unless the rules change, it will continue to be only the poor who pay. And that’s not fair.

Moshe Adler teaches economics at Columbia University and at the Harry Van Arsdale Center for Labor Studies at Empire State College. He is the author of the book “Economics for the Rest of Us: Debunking the Science That Makes Life Dismal,” recently published by The New Press.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.