Born to Run

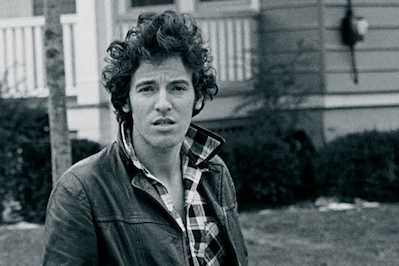

More than anyone else in popular music, Bruce Springsteen understands the people who helped elect Trump. We need the Boss' music now.

Simon & Schuster

| To see long excerpts from “Born to Run” at Google Books, click here. |

“Born to Run” A book by Bruce Springsteen

When I was a boy, our family lived in Bruce Springsteen’s hometown of Freehold, New Jersey. “A crap heap of a hometown,” he once called it, “that I love.” In Birmingham, Alabama, I once got Bruce to give me an interview for the local paper by summoning up memories of Freehold. “We called it the horsiest town in New Jersey,” I told him, “and there were so many horses they had hitching posts downtown.” He got a kick out of that.

Born to Run

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

Born to Run

Purchase in the Truthdig BazaarIn the video for his Oscar-winning song “Philadelphia,” he strolls through the Italian section of South Philly where my father grew up. Bruce and I both spent our early teens in a New Jersey obsessed with rock ’n’ roll — an AM radio paradise — and baseball. (In a great Vulture piece, Caryn Rose quibbled with Bruce’s lyrics in “Glory Days”: “It’s called fast ball, not speed ball.” Actually, Caryn, it isn’t, or at least it wasn’t. In Old Bridge, New Jersey, when Joe Casamento blew one by me in 1964, we called it a speed ball.)

I once produced a Springsteen album — actually a bootleg — in the early 1980s, of the 1978 shows at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom. Alas, the FBI grabbed part of the shipment when it came across the Mexican border and hole-punched the discs. I kept one of the wrecked records as a memento and gave one of the sets to drummer Max Weinberg, then the unofficial librarian of the E Street Band’s bootleg recordings.

My father kept my life from becoming a Springsteen song when he falsified his high school transcripts to show he graduated, enabling him to get a white-collar job and move us up to the middle class. By the time Springsteen’s first album, “Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.,” was released in 1973, the lives of the people in his songs were vastly different from my own. So why did I identify so powerfully with his grease monkeys, cops, drug dealers, Vietnam vets, laid-off textile workers and diner waitresses? I’m not the first person to ask that question about Springsteen’s work.

In my own case, it’s because I recognize that he’s writing about friends and family who didn’t make it out of their Freehold, who got left behind when the American dream moved on without them. When I hear Springsteen’s songs, I recognize a version of myself that might easily have been.

Bruce was never an innovator. He was a community college dropout who reveled in Chuck Berry, Roy Orbison, Dion, Marvin Gaye, and Phil Spector records. He was a synthesizer of all this music and, as he got older and smarter, of American literature from Steinbeck to Flannery O’Connor to Nevins’ and Commager’s “A Short History of the United States.” In the process he went from Jersey Shore dives to Madison Square Garden. The scope of his achievement is unprecedented in American pop and rock; someone, I don’t know who, quipped that Bob Dylan “wanted to be Elvis, but there was an opening for Woody Guthrie so he took it.” But Bruce is not only closer to being Elvis than Dylan, he has, at some times in his career, been closer to being Woody Guthrie.

Along the way, the stories in his albums, taken as a whole, have achieved a thematic cohesion approached by no one else in rock and pop except Dylan (though Hank Williams, given another 10 years, might have done it). Springsteen may be the greatest novelist rock has ever produced, which is probably the reason so many writers — T. C. Boyle, Nick Hornby, Bobbie Ann Mason, Tom Perrotta, Frederick Reiken and even Walker Percy – have seen in Bruce a kindred spirit.

(Hint to the Swedish Academy: If you give the Nobel to Bruce, he not only might show up but bring his guitar and play a set.)

Like Dylan, Springsteen has written an excellent autobiography, “Born to Run,” that reads better than most of the books written on him. Like Dylan’s “Chronicles, Volume One,” “Born to Run” is part memoir, part life and times, and part position paper in which Bruce sweeps away myths about his life and clarifies his stance on some issues.

He is still Catholic, sort of. “Going to Catholic school as a boy left a mean taste in my mouth and estranged me from my religion for good.” But “I know somewhere … deep inside … I’m still on the team.”

He stayed out of Vietnam by making a mess out of the forms, mumbling and bumbling and slurring his words and having a “bad enough motorcycle accident to scramble your brains. …” He got a 4-F. In the end, the man who would practically lead a national movement for Vietnam vets felt, “All I know is when I visit the names of my friends on the wall in Washington, D.C., I’m glad mine’s not up there.”

He was never a part of the flower child culture. “I was a faux hippie. … The counterculture stood by definition in opposition to the conservative blue-collar experience I’d had. I felt caught between two camps and I didn’t really fit in either, or maybe I just fit in both.” He never connected with Woodstock: “For me, it was a weekend like any other.”

Many of the girls whose names he used in those early songs weren’t taken from his life: “Sandy [from ‘Fourth of July, Asbury Park’] was a composite of some of the girls I’d known along the shore.”Freehold is his “rosebud,” but on early visits back to his hometown, “I would never leave the confines of my car.” He blames the failure of his first marriage to model Julianne Phillips entirely on himself, “At 35, I could seem accomplished, reasonably mature, and in control, but, inside, I was still emotionally stunted and secretly unavailable. … I failed her as a husband and a partner.”

His parents moved to California when Bruce was a teenager — he stayed behind to play in a rock ’n’ roll band. He finally made peace with them. Shortly before his father’s death, Bruce went out to visit. His dad told him:

“‘Bruce, you’ve been very good to us.’ I acknowledged that I had — pause. His eyes drifted out over the Los Angeles haze. He continued, ‘… and I wasn’t very good to you.’ A small silence caught us.

‘You did the best you could,’ I said.

That was it. It was all I needed. All that was necessary. I was blessed on that day and given something by my father I thought I’d never live to see. …”

Still, “the seeds of my father’s troubles lie buried deep in our blood line. So we have to watch.”

One of the eye-popping revelations of “Born to Run”: “Shortly after my sixtieth birthday, I dropped into a depression. … It lasted for a year and a half and devastated me.” And “I’ve been on antidepressants for the last twelve to fifteen years of my life. … They have given me a life I would not have been able to maintain without them.”

You feel as if you were there at the funeral of his great friend Clarence Clemons, the E Street Band saxophonist and its only black member: “The morning sun laid a pinkish veil over the St. Mary’s parking lot as we entered through the rear door and gathered bedside in Clarence’s small room. His wife, his sons, his brother, his nephews, myself, Max, and Garry [bassist Garry Tallent] prepared to say our goodbyes. I strummed my guitar gently to ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’ and then something inexplicable happened. Something great and timeless and beautiful and confounding just disappeared. Something was gone … gone for good.”

Late in life, Bruce became friends with another singer from a Jersey town. At a party in Hollywood, “There’s a tap on my shoulder. I turn around and get lost in a sea of blue. A Jersey-accented voice says, ‘It’s about time, kid,’” — it was time for Jersey’s two greatest musical legends to meet. After dinner at Frank Sinatra’s house, “We find ourselves around the living room piano with Steve and Eydie Gorme and Bob Dylan.” Now there’s a match.

“Frank moves to the piano and I get to watch my wife [Patti Scialfa] beautifully serenade Frank Sinatra and Bob Dylan, to be met by a torrent of applause when she’s finished.” After Sinatra’s funeral, Bruce leaves the church and finds himself “for a moment with Jack Nicholson on the church’s front steps. He turned to me and said, ‘King of New Jersey.’”

Near the end of the book comes a moment that Bruce had fantasized about since he first picked up a guitar. “The phone rings. Mick Jagger is on the line. I had a teenage daydream about receiving a call like this many years ago, but, no, the Stones did not need an ex-pimply faced front man for the next evening’s show. But it’s The Next Best Thing! They’re playing in Newark, New Jersey, and have decided one extra New Jersey guitar man and voice for ‘Tumbling Dice’ might get some of the local fannies wagging.”

Bruce arrives to rehearse: “… I am suddenly transported back to the little dining room I rehearsed in daily with the Castilles [his first band], except … these are the guys who INVENTED my job! They have been stamped on my heart since the chunking chords of ‘Not Fade Away’ came ripping off the little 45 I bought at Britt’s Department Store in the first strip mall in our area.

“On the way home, I kept thinking, ‘I GOTTA CALL STEVE! [his boyhood friend and E Street Band mate, Steve Van Zandt]. He will completely one hundred percent, full-tilt rock ’n’ roll crazy understand.’ He did.”

And so do I.

For real fans, though, the truly fascinating parts of “Born to Run” cover the development of Springsteen’s songwriting and music as his worldview expanded:

“The piece of me that lived in the working-class neighborhoods of my hometown was an essential and permanent part of who I was. No one you have been and no place you have gone ever leaves you. The new parts of you simply jump in the car and go along for the rest of the ride. … My music would be a music of identity, a search for meaning and the future.”

As he grew older, though, “My music began to have more political implications; I tried to find a way to put my work into service. I read and I studied to become a better, more effective writer.”

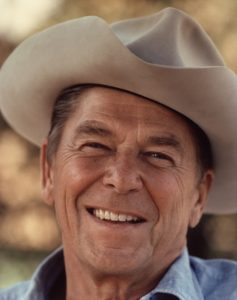

The emotional and intellectual leap came in 1978 with “Darkness on the Edge of Town.” With that album, “I’d found my adult voice.” Eight studio albums later, the songs from “Darkness” remain the core of Springsteen’s live performances.There was a time in the mid-1980s when some writers tried to pin the rise of Springsteen to his status with rock critics. In a 1985 piece for Vanity Fair, James Wolcott accused Springsteen of “having been built to rock-critic specifications.” (The piece, curiously, did not appear in Wolcott’s collected journalism a couple of years ago.). In a bizarre piece in Esquire in 1988, a writer named John Lombardi tied Springsteen’s popularity to the ascendancy of Reagan and called him “a rock critic’s dream.” These are strange accusations in retrospect — no one ever attributed the rise of John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock to their being favored by film critics.

The most prescient of writers on Springsteen’s development has been Greil Marcus. In 1980, he noted that Bob Dylan’s album, “John Wesley Harding,” was permeated with an awareness of the Vietnam War, and “It is an almost certain bet that the songs Springsteen will now be writing will have something to do with the events of November 4 [Reagan’s election]. Those songs likely will not comment on those events; they will, I think, reflect those events back to us, fixing moods and telling stories that are, at present, out of reach.”

Marcus’ judgment has been confirmed by — to pick just three albums — “Nebraska” (1982), which seems to tap into the undercurrent of sullen anxiety underneath Reagan’s Morning in America; in “Born in the USA” (1984), which spoke to us about the lingering legacy and emotional scars of Vietnam; and “The Rising” (2002), which made him the only popular artist to assuage our collective trauma post-9/11.

A couple of weeks ago I exchanged emails with an old friend I had known back in central Jersey. “Let’s play a game,” he suggested. “Let’s pick the one performer who is least likely to be at Trump’s inauguration.” Our emails crossed each other — the answer, of course, is Bruce.

There’s an irony there that Bruce might appreciate and Trump couldn’t, and it is this: No one in popular music, maybe no one in all of the arts, better understands the kind of people who helped elect Donald Trump. I don’t know what Bruce is worth financially — I suspect he’s got a lot more money than Trump — but who better deserves to be called a blue-collar billionaire?

On some level, Trump understands this, which is why he’s tried to appropriate Bruce, much as Reagan did in 1984 when “Born in the USA” was released. In a big blunder, Team Trump wanted a Springsteen tribute group, The B Street Band, to perform in a pre-inaugural event Thursday. When fury erupted among the real band’s fans, the B-Streeters backed out, saying, “We had to make it known that we didn’t want to seem disrespectful … to Bruce, his music and his band.”

In that case, they might have slammed the door on Trump back in September, when surely they read the Boss’ words in a Rolling Stone interview: “I believe that there’s a price being paid for not addressing the real cost of the deindustrialization and globalization that has occurred in the United States for the past 35, 40 years and how it’s deeply affected people’s lives and deeply hurt people to where they want someone who says they have a solution. And Trump’s thing is simple answers to very complex problems. … The whole thing is tragic. Without overstating it, it’s a tragedy for our democracy.”

I’ve been following this guy since 1973, and it sounds to me like he’s got an album in the works. He helped get us through the age of Reagan and into the Obama years. And now we need his music as much as we ever have.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.