Born Slaves: Child Labor in an ‘Adultocratic’ World

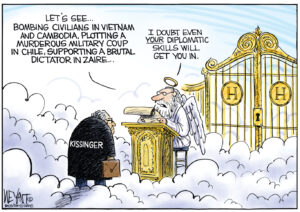

Injustice doesn’t have the same meaning for the average reader of this site as it does for a child who has grown up in precarious conditions, subjected to racism, a lack of emotional education and cultural training. Injustice doesn’t have the same meaning for the average reader of this site as it does for a child who has been forced to work. A Bangladeshi girl, Sharmin, 13, works at a plastic recycling factory as a boy plays on a heap of bottles in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on June 12, 2014. June 12 marks the World Day Against Child Labor, initiated in 2002 by the International Labour Organization to highlight the plight of child workers across the world. (A.M. Ahad / AP)

A Bangladeshi girl, Sharmin, 13, works at a plastic recycling factory as a boy plays on a heap of bottles in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on June 12, 2014. June 12 marks the World Day Against Child Labor, initiated in 2002 by the International Labour Organization to highlight the plight of child workers across the world. (A.M. Ahad / AP)

Editor’s note: This article is the latest in a series called Global Voices: Truthdig Women Reporting. The project creates a network of female foreign correspondents in collaboration with the International Women’s Media Foundation.

Click here to support the women of Global Voices with a tax-deductible donation.

“Well, my papa hit me with a board if I didn’t bring 20 bundles of firewood, which he sold in town. I was about 8 years old, and this is how I became a man — pure punches.”

Rafael is 28 years old and is incarcerated in a Chiapan jail in southeast Mexico for running a child-panhandling network. For him, child labor is part of life, part of poverty. The use of violence to control children is normal for Rafael. He forced the children to beg for eight to 10 hours a day from tourists and locals in San Cristóbal de las Casas in southern Mexico, and he took a large percentage of the earnings they received.

Although we wouldn’t want to accept that Rafael is in any way justified, there is a cultural norm that systematically accepts and replicates certain values and attitudes about poverty. In an “adultocratic” world, the children of families living in poverty are objects of exploitation, and not subject to laws or rights.

In Mexico, as in most of the rest of the world, a high percentage of children must survive by helping their family earn money however they can. Very early on, girls learn the meaning of double burden: They leave to earn their bread and later return home, where they are responsible for looking after the men of the house, and doing the laundry, cooking and cleaning.

Child exploitation is tacitly tolerated in societies in which being born into a poor family naturally implies working to survive, and in a cultural context that normalizes physical and psychological violence as an educational strategy. For the majority, this means tolerance of mistreatment, verbal abuse, scolding, humiliation and work demands that are far beyond the physical abilities of a child.

Rafael is just one example among thousands of people who have grown up to perpetuate the same exploitative behavior that they were victims of as children. He doesn’t understand why he has been imprisoned. He believes that the kids he enslaved for begging purposes had been abandoned until he rescued them and gave them work, food and a bed to sleep in. A childhood plagued by violence, emotional abandonment and malnutrition prevents the majority of these kids from developing the cognitive and behavioral skills that would allow them to differentiate between what is and isn’t ethical.

Injustice doesn’t have the same meaning for the average reader of this site as it does for a child who has grown up in precarious conditions, subjected to racism, a lack of emotional education and cultural training. In this world, surviving slavery isn’t the same as being a free citizen.

Socorro is an indigenous woman who, for the last 10 years, has found herself working as a sirvienta, or servant, in the house of a wealthy family. She is now 60 years old, and each time she visits her village in Oaxaca, she brings back young girls for domestic work; they’ll learn their duties of being obedient, useful and silent.

Socorro doesn’t agree with what the newspapers say about the rights of children. If they are born poor, she says, they must work all their lives because they can either go to school or eat. Even if they go to elementary school, she believes, they’ll end up as sirvientas, so better that they’re very good so they will have patrons who will want them to live with them and who in turn will treat them well.

She likes that now sirvientas are called domestic workers, that they can enjoy rights that she’s never had. She lived without ever resting until she was 21, when her patrona decided that she could have Sundays off, but she wasn’t allowed to visit her hometown so that she wouldn’t get up to mischief. Socorro doesn’t view herself as being enslaved by her confinement of 14 hours of work per day; her memories of life in her village are much worse.

All forms of childhood exploitation or slavery implicitly encourage victims to believe they deserve this treatment, whether because of their class, race or sex. This emotional response is a central factor in the survival of exploited children. They develop Paradoxical Adaptation Syndrome in which they resist whoever mistreats them but at the same time appreciate their help to be able to survive in an uncertain environment.

Violence as a form of discipline runs through all socioeconomic classes, but without a doubt occurs more commonly in those social groups without access to means of social, economic, educational and emotional well-being. According to UNICEF, six out of 10 children in the world (1 billion) between 2 and 14 years of age suffer frequent physical punishments at the hands of their caretakers.

Exploitation and slavery will never disappear, but rather will continue to grow and become stronger due to beliefs that, in one way or another, justify forced labor as the only solution given the immense inequality in the world. Without a doubt, sex slavery is the most horrifying form of slavery, but the most prevalent form is labor exploitation, which exists via coercion, violence and deception. Children educated through violence and coercion normalize it, not reporting it or seeking help. In their emotional universe, the concrete possibility of a right to a life free of violence doesn’t exist.

Deception, on the other hand, always contains elements that make children feel that they matter to the adult lying to them in order to exploit them. This dynamic functions perfectly, because for those growing up in this context of abuse, aggression and lack of affection, it is difficult to develop a moral compass or to develop tools of empowerment. This is why, when authorities and civil organizations come to the rescue of exploited children, the children often demonstrate great hostility, distrust and violence. For the majority of males rescued from labor exploitation, physical violence is the only tool that they know to express their discontent. In front of their captors, they are subject, and in front of their rescuers — until they receive therapeutic services — they sometimes rebel with virulence.

In this context of normalized abuse, there are 2 million children across the world trapped in the commercial sex industry. During the investigation for my book “Slavery Inc.,” I was able to document that for each sexually exploited girl, there are at least 100 men creating demand for brothels in tourist areas and elsewhere.

As such, child slavery has various forms — the first being familial, in which the child is exploited for his or her own survival. The second is created by consumers, whether of the sex industry or those of clothing, footwear, food or toys. Adults who demand inexpensive goods and manufacturers that must compete in a materialistic world of almost pathological and compulsive consumerism both require cheap labor.

When I was in India investigating trafficking networks, I spoke to the owner of a clothing factory who would buy products to export to Mexico. His main argument was that the girls he had working for him as seamstresses weren’t aware of trade unions or employee rights; their labor was stable, cheap and secure. From Puebla, Mexico, to Sri Lanka and China, millions of maquiladora owners are searching for a way out of legal requirements that protect the labor rights of adults.

In September 2014, for the first time in history, Cambodia’s eight largest clothing maquiladoras were forced to raise the wages of their workers. This happened only after a huge protest and strike movement. The Cambodian maquiladoras generate one-third of the country’s GDP and have historically been the cradle for the slave labor of young girls and teenagers.

This response by the maquiladora owners happened because the executives of Zara, H&M, British New Look and Primark wrote to Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, telling him that they would keep manufacturing there only if workers’ salaries were raised. These brands didn’t do this out of goodwill, but rather thanks to great reporting by journalists and social activism via international human rights networks that impact corporate responsibility. This is an exceptional case, but it could be the first of many.

What is clear is that the majority of Asian and Latin American countries with serious levels of poverty have normalized labor exploitation, particularly that of children between 12 and 17 who aren’t aware of their rights and who feel grateful to have a job. In our overpopulated world, no government has the ability to eradicate child labor unless it changes economic policies to reduce social inequality. The Child Labor Public Education Project has shown that giving adults better wages and benefits (such as health insurance and day care) can prevent their children from having to work, and therefore, allow those children to stay in school.

When mothers and fathers have the possibility of improving their labor conditions via unions, their children gain in health and well-being. Hence the fight for unions and labor rights is a lethal weapon against complicity in childhood labor. Thanks to social pressure, quality journalism and figures that demonstrate the effectiveness of organized labor, many businesses are now compelled to change their codes of conduct to include rights for children in their wage policies.

In Mexico, approximately 40 million people, or about a third of the population, are under 18. Even with the great efforts of Mexican families, four of every 10 children — approximately 21 million — live in poverty. Of those, 4.7 million exist in extreme poverty. Eight of every 10 indigenous children are born into poverty. In this context, more than 3 million children work and 6.5 million teenagers and youth are out of school.

Their vulnerability and impoverishment have caused Mexico to become a hell for the sexual exploitation of children, In fact, Mexico is one of the five countries with the most child pornography in the world and has more than 30,000 teenagers recruited for organized crime, which many believe is the only way out. In this incredibly complex scenario, Mexico invests only 6 percent of its GDP on its children, and of this, less than 1 percent goes to special protection.

UNICEF calculates that across the world there are 150 million children between 5 and 14 years old who work. Many are assuming adult responsibilities before they even reach adolescence.

These figures reveal a cycle of violence that incessantly repeats in a world in which there is doublespeak about childhood. On the one hand, there is poetry written about the innocence of youth that idealizes maternity. On the other, millions of boys and girls breathe for the first time without yet knowing that someone out there is convinced that they have been born — like their mothers — to be slaves.

The campaign End Human Trafficking Now! was initiated by the Suzanne Mubarak Women’s International Peace Movement in partnership with the business community in January 2006. It is the first worldwide initiative that places the business community at the forefront of anti-trafficking efforts. The campaign encourages business to endorse and implement the Athens Ethical Principles and assist businesses in applying zero tolerance and contributing to anti-trafficking efforts. Click here for more information.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.