Borders, Bullies and Global Health

Australian Prime Minister John Howard is hurting politically, and so he has despicably turned against the vulnerable, arguing recently that Australia should have a blanket ban against HIV-positive immigrants.“HIV migrants pour into the state.” So read a headline in Melbourne’s Herald Sun on April 13. On the same day, Australian Prime Minister John Howard was interviewed on Southern Cross radio in Melbourne. He was asked to give his own views regarding HIV-positive immigrants. He answered that a ban on such immigrants would be a good general rule, though there might be humanitarian exceptions. His remarks have caused a storm of protest among healthcare professionals, scientists and community groups in Australia.

If we wonder why Howard has weighed in on the issues of public health and immigration at just this time, there are at least two persuasive reasons. A new medical study from the state of Victoria claims that the number of people with HIV who have moved to Australia since 2004 has nearly tripled. Those numbers are disputed in the Australian medical community. Howard knows little about global epidemics and still less about epidemiology, but he is a calculating politician. Australian reporters asked him direct questions about this study. That is the first reason.

The second reason is plainly the partisan politics of Australia, and more particularly the nearing elections. Epidemiology in any nation is never quite an exact science, but national narratives about purity and pollution belong more properly in the realm of mythology. The boundary between that mythic realm and partisan politics is not always fixed or clear. Howard either cannot or will not make the necessary distinctions between a disease such as AIDS and a disease such as tuberculosis. This may be simple ignorance. But it is also politically convenient in the current contest for state power.

John Howard and his deeply divided Liberal Party have been getting low scores in polls of the Australian public. His main political rival is Kevin Rudd, a dynamic leader of the Labor Party, who has a chance to become prime minister after the next big elections. Australia has a parliamentary system and no fixed election dates, so elections could occur fairly soon but could come as late as December.

Howard, who received a visit from U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney in February, is staking out political ground not only as a defender of Australian culture and borders but as one of the leaders of the free world. So, while we can feel confident that Cheney thanked the prime minister for his continuing membership in the dwindling “coalition of the willing,” it’s unlikely that Howard’s American visitor would have attempted to dissuade him from raising the issue of HIV and immigration.

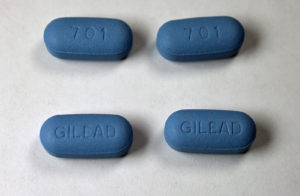

“The United States has had these sorts of strict entry restrictions on HIV for many, many years,” said Yusef Azard of the National AIDS Trust. “It’s got the highest rate of HIV in the developed world. So it doesn’t actually do any good. People go underground. Stigma and discrimination increases in the country and makes the response to HIV all the more difficult.” In 1987 HIV was included in a U.S. immigration law among other diseases judged to be a “communicable disease of public health significance.” The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services attempted to remove HIV and certain other conditions from the immigration exclusion list on the grounds that these illnesses are not spread by casual contact and are not transmitted through common vectors such as food and water. In May 1993, Congress approved a law codifying the exclusion of HIV-positive immigrants. Despite campaign promises to the contrary, President Bill Clinton signed this bill into law. In this way the United States set an early bad example.

Howard gives the wrong diagnosis

A recent study from the health department of the state of Victoria showed, according to the Australian news announcer Mark Colvin, “an alarming increase in the number of HIV-positive people who’ve moved there from interstate and overseas.” When Howard was asked to respond to this report on the radio, he was also asked bluntly whether HIV-positive people should be allowed to immigrate.

“Well, I would like to get a bit more counsel and advice on that,” Howard answered. “My initial reaction is no. There may be some humanitarian considerations that could temper that in certain cases, but prima facie, no. But it would require a change in the law, yes.”

Simeon Beckett, president of Australian Lawyers for Human Rights, has suggested that such counsel has already been freely and fully given. Beckett reminded the prime minister and the minister for immigration that “certain protections for people who are suffering from a disability such as HIV or AIDS” do exist under Australia’s Disability Discrimination Act.

Howard added, “I think we should have the most stringent possible conditions in relation to that nationwide, and I know the health minister is concerned about that and is examining ways of tightening things up.”

“It’s very tight already,” responded Don Baxter of the nongovernment group the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. He said HIV tests were already among the health checks given to prospective immigrants. Most HIV-positive applicants have been rejected, and the reason given is that they would place an unfair financial burden on the public health system.

Chris Lemoh, an infectious disease specialist who studies HIV and AIDS among African immigrants in Victoria, condemned Howard’s comments.

“It’s a hysterical overreaction,” Lemoh said, “it mixes racism with phobia about infectious disease. To not allow people to come on the basis of any health condition is immoral, it’s unethical and it’s impractical to enforce.”

Howard has some trouble distinguishing between an infectious disease such as HIV and AIDS, which is spread primarily through intimate sexual contact and through injection drug use, and a genuinely contagious disease such as tuberculosis, which can be spread through sneezing and coughing. Howard has said Australia places immigration restrictions upon people with tuberculosis and thus he supports strong restrictions against people who test positive for HIV.

Public health campaigners in Australia have argued that Howard is wrong on both medical and legal grounds. An HIV/AIDS legal center stated that “the vast majority” of HIV-positive immigrants were already screened out and already blocked from entry. Even so, a minority of HIV-positive immigrants have been granted citizenship on humanitarian grounds, especially when they have been family members, spouses or life partners of Australian citizens.

The website of the Australian Immigration Department differs from the prime minister’s account of the existing rules and laws:

“A positive HIV or other test will not necessarily lead to a visa being denied. The main factor to be taken into account is the cost of the condition to Australia’s health care and community services.”

The Immigration Department’s website also states that not all immigrants with tuberculosis are automatically barred from entering or living in Australia. If a medical treatment has been successful or if tests indicate a particular TB case is “non-active,” this is taken into account. This is the guidance given on the website:

“TB is mentioned in legislation as precluding the issue of a visa, but opportunity is given to enable an applicant to undergo treatment in most cases. …” As long as medical care and monitoring are ongoing, the website states clearly, “Your visa is not at risk, once in Australia, no matter what status of tuberculosis is diagnosed.”

Drug-resistant strains of gonorrhea and of tuberculosis, among other diseases, are being monitored by doctors, scientists and epidemiologists around the world. Medical testing, reporting and treatment are not equally distributed, of course, across all borders. All of these factors are worth consideration in public health programs, in human rights campaigns and in immigration policy. But because common sense and humanity are shown to immigrants suffering from a disease such as tuberculosis, if we trust the account given by Australia’s Immigration Department, then the same decency is deserved by immigrants suffering from a disease such as HIV and AIDS.What do the numbers really tell us?

Prime Minister Howard’s comments came soon after Health Minister Tony Abbott asked a committee of chief health officials to consider new national policies for people living with HIV and AIDS. In turn, that request followed two highly publicized cases of HIV-positive men accused of trying to spread the disease.

All people over the age of 15 who apply for permanent residence in Australia are tested for HIV, and people under that age are tested if either of their parents is HIV-positive. People under 15 are also tested if there is medical reason to consider a possible infection, or if the applicant is seeking specific kinds of visas related to adoption or an unaccompanied humanitarian visa. Spouses, life partners and family members of citizens are generally given special consideration.

According to an April 14 article in The Australian, “A 2005 study on HIV and migration in Australia found that many migrants found out about their HIV-positive status only after undergoing the Immigration Department health check.”

State policies that encourage immigrants to lie or to avoid medical care and testing plainly do not serve the cause of medical care and education. These policies undermine the very public trust that brings together medical professionals and people in trouble, in pain and in need.

Figures suggesting a sharp rise in the number of HIV-positive immigrants are now disputed by some leading AIDS and healthcare groups in Australia. Bronwyn Pike, health minister for the state of Victoria, had been widely quoted as stating that the number of interstate residents and immigrants arriving in the state with HIV had risen from 16 in 2004 to 70 in 2006. But Baxter of the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations said in a Sky News broadcast, “The Victorian minister has given a completely misleading account of these figures.” According to Baxter, only 20 people were diagnosed with HIV overseas and most were born in Australia or New Zealand.

Even when considering this number, the executive director of the Victorian AIDS Council, Mike Kennedy, said “that more than half of those [20] were born in Australia or New Zealand, which brings the number down to nine [who were born overseas].” An Australian born overseas who contracted HIV in Australia and was later diagnosed out of that country would have be included in that figure. As Kennedy concluded, “The numbers might be really, really tiny.”

The numbers simply do not approach any standard of good science. But numbers alone cannot be expected to tell the story of HIV and immigration anywhere on Earth; one must know the stories behind the numbers. Epidemiology may not be an absolutely exact science, but it is a science requiring a much higher level of evidence and approximations.

White Australia: an old ghost revisiting?

In 1998, Prime Minister Howard argued for greater immigration restrictions and acknowledged later (in tortured syntax worthy of his friend Dubya) that he had paid a political price for his views: “I’m not in favor of going back to a White Australia Policy. I do believe that if it is — in the eyes of some in the community — that it’s too great, it would be in our immediate-term interest and supporting of social cohesion if it [immigration] were slowed down a little, so the capacity of the community to absorb it was greater.”

The “White Australia Policy” is a catch-all term to encompass the laws and regulations restricting nonwhite immigration to Australia from about 1900 to the early 1970s. White Australia also refers to the historical campaigns designed to promote white immigration in the same period. By the 1940s this brand of racial populism was pulling apart and fragmenting, and legal reforms opened the way for greater nonwhite and non-British immigration. The Australian government passed the 1975 Racial Discrimination Act in that year, which officially removed many of the old racist barriers to immigration.

The labor movement in Australia has both a troubling and marvelous history. As in the United States, racial divisions often ran right through the working classes. Though examples and episodes of solidarity across racial lines are part of Australia’s union and labor history, the “native” labor movement also began a series of protests against “foreign” workers in the 1870s and 1880s. Many of the workers considered non-Australian were Pacific Islanders. These “Kanakas” were brought into Australia as indentured workers. Asian workers, including many Chinese, were subjected to low wages and poor working conditions. They faced racial exclusion from most major unions at that time.

In a classic example of the contradictions of class, resistance to immigration restrictions often came from wealthy rural land owners. (Consider the deep divisions within the Republican Party in the United States today regarding workers who migrate north across our national southern border. The Democratic Party is also compromised on this issue by its own class alliances with the Republicans.) Between 1875 and 1888 all Australian colonies outlawed all further Chinese immigration, though those who were already residents officially retained the same rights of citizenship as workers who had arrived from Europe.

By 1901, however, the new Federal Parliament passed new legislation to “place restrictions on immigration and … for the removal … of prohibited immigrants.” The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 was modeled in part upon similar contemporary legislation in South Africa. Edmund Barton, the prime minister, argued in favor of the bill in this manner: “The doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman.” The Aboriginal peoples simply did not figure in that equation.

The White Australia movement threw a long shadow over Australian politics, even as late as the racial nationalism of the One Nation Party, which received 9 percent of the vote in the federal election of 1998. At the peak of the party’s influence, one of its leaders, Pauline Hanson, said:

“I and most Australians want our immigration policy radically reviewed and that of multiculturalism abolished. I believe we are in danger of being swamped by Asians. Between 1984 and 1995, 40 percent of all migrants coming into this country were of Asian origin. They have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate.”

About a decade later, in December of 2006, the former One Nation leader was once again using the old racial rhetoric. She had made herself infamous for her public views on Asian immigrants and Aboriginal welfare. In her maiden parliamentary speech in 2006, she turned her attention to Muslims and Africans.

“We’re bringing in people from South Africa at the moment. There’s a huge amount coming into Australia who have diseases; they’ve got AIDS. They are of no benefit to this country whatsoever; they’ll never be able to work. And what my main concern is, is the diseases that they’re bringing in and yet no one is saying or doing anything about it.”

John Howard has just said plenty about it, though he takes care to speak in a more diplomatic code. What the Liberal Party may actually do if it wins the next election is an open question. An Australian blogger named Olney Garkle (writing at the website bilegrip.com) looks toward a chastened and renewed Liberal Party. Whatever his ideals and illusions may be, maybe he shares them with a significant number of Liberal Party members:

“But is the Federal Liberal Party really the Liberal Party as we used to know it? Not at all. It is, in effect, the John Howard Party, the JHP. There are but a handful of true liberals left in Parliament. The rest have sold out to mankind’s lowest instincts as personified by their leader. … A Labor victory will consign remnants of the almost terminally divided Liberal Party to oblivion for several elections. But once purged of extremist Howardites, it will return as the other party our democracy must have.”

Two Australian AIDS activists respond

Interviewed for this article, two gay Australian AIDS activists commented upon Howard’s ambitions — and his declining fortune in Australian public polls.

Peter Cashman was a founding member of Los Angeles ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). He has lived in the United States for 25 years but follows Australian politics and culture closely. We talked by phone April 13 and I asked him what he thought of Howard’s recent statements on immigration and HIV.

“Pandering to his base,” Cashman said. But he underscored the irony of Howard speaking for the people of Australia on the issue of HIV and healthcare:

“Australia has made many cutting-edge contributions in health education and HIV prevention programs. Australia learned a lot from — and gave a lot back to — the whole international movement of AIDS activism.”

Cashman pointed out that the total current figure of AIDS-related deaths in Australia is just over 6,500. That is no insignificant number, but given the total population of Australia it is a fairly small number. Especially, as Cashman noted, if we compare it to the AIDS-related deaths in the County of Los Angeles alone. Beyond the demographics and statistics, he underscored another point:

“Generally, even quite conservative governments in Australia — and Howard’s Liberalism is quite conservative — have deferred by and large to public health and scientific communities on HIV and AIDS issues. Howard has really cut a different figure in this political season. Howard’s polling numbers are probably the lowest they’ve ever been. Of course, it’s not all about him — I would also acknowledge that Australia has one of the more restrictive HIV immigration policies in the world.”

Between the letter of the law and the spirit of decency, there has been room in Australia for interpretation. Howard, however, has just spoken as if that is an annoying political loophole that is best closed before the elections in late 2007 or early 2008.

Paul Kidd is an Australian journalist, AIDS activist and blogger who responded by e-mail to my e-mailed questions. As I saw by reading his blog — cheekily titled buggery.org — his husband, Brent Allan, is an HIV-positive immigrant to Australia. I asked Kidd how they were able to stay united as a couple and win Allan’s case. How did the Australian authorities include him among the exceptions?

“After being rejected by the Department of Immigration,” Kidd replied, “we took our case to the Migration Review Tribunal, which has power to adjudicate these matters. Essentially our argument was that we had a genuine relationship and a strong attachment to Australia, and that if Brent were not granted permanent residence, we would have to separate. On compassionate grounds, our application was successful. It took four years and a great deal of money to make that happen, however.”

In the course of discussing the racial politicking around AIDS and immigration, running the full spectrum from implicit to explicit, Kidd added this piece of the puzzle:

“Howard has also been criticized for his handling of the so-called Tampa Affair, a diplomatic standoff between Australia, Indonesia and Norway which occurred during an election campaign in 2001. The MV Tampa, a Norwegian-registered vessel, rescued 438 mostly Afghan refugees en route to Australia from Indonesia. Howard ordered the master of the ship to return the refugees to Indonesia, although under international law they should have been taken to the nearest port, which was Christmas Island, part of Australian territory. During the standoff, Howard declared: ‘We decide who comes into this country and the circumstances in which they come.’ This infamous slogan more or less summarizes the Howard government’s approach to asylum seekers, and has been used politically by Howard’s party, the Liberal (i.e. conservative) Party.”

Gambling with the debased currency of racial and sexual fears, Howard may gain some political capital within his faction of the Liberal Party. But that party may still suffer a truly sweeping and historic loss to the Labor Party in the next big elections. Howard’s main political rival, Kevin Rudd, is a Labor Party MP, Member for Griffith (Queensland), and may become prime minister. Rudd is also unafraid to acknowledge the uglier history of colonialism in Australia, and the racial background radiation and fallout that still remain. I would not forecast whether Rudd will steer the Australian Labor Party in the same direction as Tony Blair steered “New Labour” in Britain. If he does journey with such trimmed sails and flags, then the ill winds of Reagan and Thatcher have not yet spent their driving force upon global politics.

Scott Tucker is a writer and democratic socialist. He was a founding member of ACT UP Philadelphia and of Prevention Point Philadelphia, a harm-reduction and syringe exchange program. His book of essays, “The Queer Question: Essays on Desire and Democracy,” was published by South End Press in 1997. Open Letter, his website, was recently redesigned and will open again later this spring.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.