#BlackLivesMatter and the Untold Story of Altamont

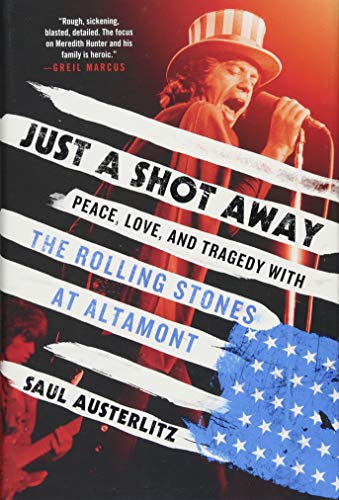

You've seen "Gimme Shelter," but have you heard of Meredith Hunter? A new book re-examines one of the epochal events of the 1960s. Macmillan

Macmillan

“Just a Shot Away: Peace, Love, and Tragedy With The Rolling Stones at Altamont”A book by Saul Austerlitz

Reviewed by Tim Riley

In that great ballooning myth of the ’60s, Altamont ranks right up there with the anti-war demonstrations at Chicago’s Democratic Convention (1968), the Charles Manson murders (1969), and the National Guard killings at Kent State (1970). Since the event entered wider consciousness through “Gimme Shelter,” the 1970 feature documentary by the Maysles brothers, the story has ripened into its own conundrum, both as history and cliche, prophecy and sinkhole.

It has produced at least one literary masterpiece in Stanley Booth’s “Dance With the Devil: The Rolling Stones and Their Times” (first published in 1984), by a participant and good friend of musician Gram Parsons, which still repays close reading. Photographer Ethan A. Russell wrote his account of the tour with a picture book, “Let It Bleed,” in 2009. Last year brought “Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day,” a searing piece of reporting by longtime Bay Area scribe Joel Selvin.

In the new “Just a Shot Away,” author Saul Austerlitz finally frames the narrative around Meredith Hunter, the 18-year-old black man stabbed and beaten to death by the Hells Angels, who goes unnamed in “Gimme Shelter.” Although uneven, Austerlitz updates this incident for our #blacklivesmatter moment, and retells a crucial story: of a black man cut down in the front row of a “free” concert, planned with a breathtaking naivete, that jolted into violence.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Just a Shot Away” at Google Books.

Like the ’60s, the event has its own fittingly twisted history: the early reports, filed by reporter Jim Wood before the Stones stepped on stage, ran in the San Francisco Examiner and then AP wires dubbing it “Woodstock West.” “Some Were Born … Two Died,” ran the headline, but medical staffers knew that the urban legend of festival births, launched at Woodstock four months earlier, might well have been a ploy by promoters to cover up the violence.

It took a troupe of Rolling Stone reporters to write up a corrective report in a single issue (dated Jan. 21, 1970), famously edited by John Burks. Even with its own real-time inaccuracies, the Rolling Stone account made that magazine’s reputation, and remains a pillar of participatory journalism.

The following year, the “Gimme Shelter” documentary came out, which cut together concert footage from throughout the Rolling Stones’ otherwise triumphal tour and crested with the unbearable Altamont sequence. Austerlitz reveals how the film’s meta-narrative, conceived by editor Charlotte Zwerin, saved the project. “The problem, as Zwerin saw it,” Austerlitz writes, “was that the Rolling Stones needed to be confronted with the proof of their own failures.” So the Maysles set up a camera at a London editing suite and invited the Stones to watch the footage together. In the end, only Mick Jagger and drummer Charlie Watts attended, and their reactions, or non-reactions, ended with a famous freeze-frame of Jagger making elusive eye contact with the camera.

Jagger’s knowing glance serves as the movie’s indictment: The Hells Angels stabbed and beat Hunter to death in the front row, but the Stones actually funded the film, and recouped royalties on it as a trailer for their live album, “Get Yer Ya-Yas Out,” released in September 1970.

Screening alongside “Woodstock” that same summer, “Gimme Shelter’s” Altamont assumed its symbolic stature as a metaphor for a curdled utopia, and fixed itself as the dark pole of the ongoing culture wars. Movie critic Michael Sragow called the film “a red-hot paradox: an exhilarating sober-upper,” and longtime Village Voice rock critic Robert Christgau pointed out, “Writers focus on Altamont not because it brought on the end of an era but because it provided such a complex metaphor for the way an era ended.”

To his everlasting credit, Austerlitz, writing a generation later, doesn’t claim any more vast cosmic insight than his predecessors. His portrait of the Hunter family, who settled in Berkeley during the war, reads like an anguished Toni Morrison novel: Meredith’s mother, Altha, who descended into schizophrenia, yielded child-rearing to daughter Dixie, Hunter’s senior by just eight years.

Austerlitz walks us through Hunter’s childhood all the way through the murder trial and acquittal of Alan Passaro, the man who stabbed him, for a story that rings nauseatingly familiar. With the Angels playing the role of “cops,” this new frame turns into a contemporary analog to stories about Trayvon Martin or Michael Brown or Eric Garner. “Two days before Altamont,” Austerlitz points out, “Chicago police had killed Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark as they lay asleep in their beds.” (Austerlitz confirms that authorities who tested Hunter’s gun discovered it had never been discharged. He does not clarify what he implies earlier: that no chamber was even loaded.)

Coming to terms with Altamont means coming to terms with the Rolling Stones, who escaped the scene via helicopter and flew off through a different wormhole. “The Stones are making miraculous music, despite everything,” wrote Rolling Stone in its account. “It’s just amazing. There could be no worse circumstance for making music, and the Stones are playing their asses off. Jagger is incredible. They all look like they’d rather be anyplace else. But it’s getting better and better. Driving, powerhouse waves of rhythm roll on and on.”

The Stones never made an official statement about Hunter’s death, never reached out to the family, so “Gimme Shelter” stands as a profoundly negligent gesture. They carried on to mount the most hyperbolic career in rock history, filling stadiums into their early 70s. However, as Austerlitz points out, context matters, not only in 1969, but in how the band has seen itself since. “Dead Flowers,” their vintage country move from 1971’s “Sticky Fingers,” might be the closest they got to a hippie farewell. But in 1993, when bassist Bill Wyman left the band, they hired Darryl Jones, a leading session player of color, who has played with them ever since. He does not appear in official band portraits.

Tim Riley has written several books on rock history, including “Lennon: Man, Myth, and Music,” which Kirkus Reviews hailed as a biography of the year. He oversees the Riley Rock Index, music’s metaportal.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.