Black Women Spearhead a New Southern Union

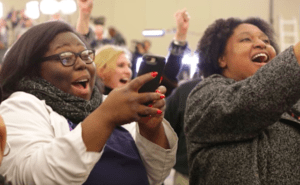

Black women nearing retirement age who work in the fast food and home care industries have helped pave the way for the Union of Southern Service Workers. Photo courtesy of Union of Southern Service Workers.

Photo courtesy of Union of Southern Service Workers.

Cummie Davis, a certified nursing assistant in North Carolina, still speaks wistfully of the one union job she’s had in her life. It was at a telecommunications company, and she was forced to leave the position in 1993 when she couldn’t find day care options for her son, who was born with hydrocephalus, a condition that causes fluid buildup in the brain. The money accumulated in her union job’s retirement plan was enough to support Davis for seven years. The 401(k) plan—not to mention the health care, paid time off, and other union benefits—now seem like a very distant reality.

Davis has spent decades caring for others, but in her 60s, accessing care for herself has been a struggle. Davis cannot afford health insurance. She relies on “hospital charity care” for lowered prescription rates and low-cost appointment co-pays. Without charity care programs, Davis said she has “no idea” how she would obtain medical care.

Home care is one of the fastest-growing occupations in the U.S., and the need for these workers is only expected to skyrocket in the coming years as the population of people over the age of 65 doubles. But Black women like Davis, who make up a large percentage of this workforce, are also aging—and they’re entirely without a safety net. Thirty-two percent of home care workers are age 55 and over, and they are the working poor. Wages in the field have stagnated for at least a decade. The median hourly wage for home care workers who perform physically and emotionally demanding work—work that has also been deadly during the pandemic—is $12.12.

At 61, Davis should be looking forward to her golden years. Instead, she works two jobs, splitting her time between working at an assisted living facility and providing home care to disabled adults—a job that requires her to stay with patients overnight without compensation. The position pays $13.50 an hour, but Davis is not paid for the hours between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m.

“These conditions really put a strain on me,” Davis said. “I do love my work. I love working with people and making sure they have the care they need. I’m giving [my employer] everything they need on the job, so they should give me what I need to sustain my life.”

The precariousness that Davis experiences in the workforce is not specific to home care workers. Across the service industry, low-wage workers are fighting for their survival, enduring poor treatment, unsafe work conditions, and poverty wages without the help of health insurance, retirement accounts, paid sick days, or other benefits. These inequities are compounded in the South, where historically racist right-to-work laws and preemption laws coalesce to keep service workers—and Black and Latinx people in particular—mired in poverty.

In the 1940s, Southern states began to enact right-to-work laws, making it illegal for union membership to be a condition of being hired and prohibiting the collection of union dues from non-union workers. These laws, rooted in the Jim Crow South and “built on racial division and cheap labor,” continue to have a chokehold on unions. States like North and South Carolina consistently have the lowest union membership rates in the country.

Using data on wages, worker protections, and rights to organize, the nonprofit organization OxFam ranked the best and worst states to work in the country last year. The top six worst states to work in were located in the South, the region with the highest share of the country’s Black population. This is not a coincidence. Black domestic, agricultural, and service workers were systematically excluded from labor protections and union rights. This legacy continues to reinforce racial disparities across the region.

Davis’ home state of North Carolina took the prize in OxFam’s ranking as the absolute worst state to work in the U.S. The home care worker said she is tired of operating under these circumstances and doesn’t want young people to be saddled with the same conditions.

“Where we live [in the South], racist lawmakers and companies were so afraid of the power of workers unionizing across racial lines they passed legislation to stop us and to divide us. We’re in a new era, but these low wages and bad work conditions are still killing us. We can’t wait anymore for labor laws to change. We need to fight for these changes now—for us and for the younger generations,” Davis said in a November phone call.

When Davis spoke to Prism, she was in South Carolina with more than 100 other service workers for a summit she co-organized. One day, she said, the event will be recognized as a “historic” moment in the fight for workers’ rights.

Working across sectors isn’t just a way to build collective power, it’s a way to circumvent the challenges of organizing store by store.

In November, workers from across the South gathered in South Carolina to say “no more”: No more low wages. No more going without health insurance, sick leave, control over their own schedules, and protections from discrimination and harassment. No more exploitation. The vehicle that will help make these demands a reality is the Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW), a first-of-its-kind cross-sector union offering membership to fast food, retail, warehouse, care, and other service industry workers across North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama.

USSW is a continuance of Raise Up, the very active southern chapter of the Fight for $15 and a Union that formed in 2013 and took root in North Carolina. USSW will function as a part of the Service Employees International Union, a labor union that represents nearly 2 million workers in the U.S. and Canada.

According to Mama Cookie, a fast food and home health care worker who’s become a sort of legend in Durham, North Carolina, USSW’s cross-sector model will be crucial to its success. On the surface, it may seem like the employment issues that impact home care workers don’t have much to do with the challenges Amazon workers face in labor violation-ridden warehouses, but there’s more overlap than there appears to be.

“Low wages, no health care, no benefits, no affordable housing, no respect—that’s what we have in common,” Mama Cookie explained.

Working across sectors isn’t just a way to build collective power, it’s a way to circumvent the challenges of organizing store by store. Employee turnover is high in sectors where labor standards are low. Needless to say, low-wage service jobs have incredibly high turnover rates, making it difficult to pull off union elections at individual company locations. This is part of the reason why workers have struggled to unionize individual Starbucks stores and Amazon warehouses, although, ironically, unionized workers are more likely to remain in their jobs. The USSW, on the other hand, will follow workers wherever they go—whether they hop from one fast food restaurant to another or transition from doing care work in Alabama to retail work in Georgia.

“In the South, they told us unions wasn’t for us, and they divided us by race and by jobs,” Mama Cookie said. “Now we are coming together because there is power in that. When young folks and elderly people, Black people and white people, when all these working folks stood up in South Carolina and said yes to this union, they meant it. The South deserves better. If New York and California can have these unions, why can’t we?”

If the new union of the South can successfully get service workers a seat at the table to fight for fair pay, it would give the largest and most marginalized workforce in the South a real shot at financial stability—and better health outcomes.

Income has a very real impact on health, and the pandemic has illustrated that poor Black and brown people are living at a deadly intersection. Low-wage workers disproportionately experience greater health risks, mental health problems, and limited access to care. These issues are compounded for older workers of color living in the South, where health disparity gaps are far worse than in other regions of the U.S.

Forty-four percent of all U.S. workers—53 million people—earn low hourly wages, meaning they make less than two-thirds of the median wage for their region. Of those workers, 30% live below 150% of the federal poverty line, or about $41,500 for a family of four in 2022. Employers in the service industry do not pay enough to cover even basic necessities, which wreaks havoc on the lives of low-wage workers. Even those who work multiple jobs still find themselves struggling with housing instability, food insecurity, and critical gaps in necessary health care.

Fast food employers put American families in particularly precarious positions by resolutely paying rock-bottom wages. The median pay for fast food jobs is $8.69 an hour, and 87% of fast food workers do not receive health benefits from their employers. Those opposed to raising the minimum wage, which hasn’t increased for more than a decade, often perpetuate the myth that it’s largely teenagers who would benefit from receiving $15 an hour to “flip burgers.” The reality is that two-thirds of food workers are over the age of 24, one-third are parents, and more workers 55 and older earn minimum wages than those 19 and younger. All workers deserve a liveable wage, and while $15 an hour would lift millions of people out of poverty, in today’s economy, it’s still not enough to sustain single adults and families in many regions of the country.

Mama Cookie doesn’t need statistics to understand the implications of low wages in the service industry. She lives with the reality of it every day, and these numbers and figures don’t illustrate the generational toll the industry’s low wages have had on families like hers.

“The pandemic had everybody talking about ‘essential’ workers for a minute, but in my family we’ve been essential workers for generations,” she said. “It ain’t just like I came along and did this work. My grandmama worked in a restaurant. My sisters and brothers worked in restaurants. My children have worked in restaurants. The thing is that they never had a voice because nobody ever cared about what they felt. This is why I fight. They have taken so much from us, and I just can’t stand it anymore.”

Across Raise Up and now USSW, Black women have emerged as powerful voices and leaders in the labor movement,

The USSW is the result of a core team of worker leaders across the South, but there is no overstating the role Mama Cookie and Davis have played in helping to push the new union forward. The women also co-organized the November summit, where service workers from South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama officially signed USSW union cards and adopted their demands.

Davis is 61. Mama Cookie is 63. Both women talk about “the fight” a lot: the fight for workers’ rights, the fight for higher wages, fighting for themselves, fighting for young people. Davis, who’s been in North Carolina’s workers’ rights movement for nine years, said that she’s had to fight her entire life—to be heard, to be respected, to get what’s owed to her.

“The truth is yes, it’s exhausting,” Davis said. “But what other choice is there? Nothing is going to get handed to us. We cannot sit back and expect that change is going to come. That’s why I got involved [in organizing]. I’m speaking and believing and knowing that change is going to come because I know how hard we are going to fight for it.”

In a perfect world, Davis and Mama Cookie would be easing into a restful retirement. Instead, they are gearing up for a years-long battle for service workers’ rights. Of course, there is frustration in this. Mama Cookie has worked since she was 13 years old. She’s been in the workforce for 50 years. When will she be able to rest?

“People in my situation don’t get to rest. We still have to go out and work because the retirement money is not enough for us to stay at home and take care of ourselves. They are pushing older people back out there, but the mistake [employers] make is that they don’t expect us to stand up and fight. They think we’re just going to put our heads down and work to make ends meet. No, ma’am. We’re not doing that anymore,” said Mama Cookie, who actually looked into early retirement. She learned she’d have to survive on $732 a month in Durham, where the rapid gentrification of Black neighborhoods is displacing low-income, longtime residents like her.

Across Raise Up and now USSW, Black women have emerged as powerful voices and leaders in the labor movement, shedding light on the realities of low-wage service workers and disrupting commonly held beliefs about what can—and cannot—be done in the South. Through their organizing and leadership, Raise Up and—by extension—USSW have built a multigenerational, multiracial labor movement across the South, a region shaped by the Black Freedom Movement that continues to be home to some of the most innovative organizing in the country. While women like Davis and Mama Cookie may be reluctant leaders in the fight for the South’s service workers, their influence is undeniable.

Derrick Bryant is a 28-year-old from Durham who signed his USSW union card in November. As part of the South Carolina summit, Bryant publicly shared his story for the first time, detailing how when he was homeless, a Red Roof Inn manager found him sleeping behind storage containers in the hotel parking lot and offered him a job and a room. What initially seemed like an unbelievably generous gesture was soon revealed to be an act of exploitation. The room was filled with mold and cockroaches, and Bryant found himself on-call 24/7, putting in hours and doing work far outside of his job description. He also experienced wage theft. His paycheck only reflected two hours of work when he was putting in 10-12-hour days.

Bryant is deeply motivated by what he’s learned from Mama Cookie, whom he says has helped him understand that you don’t have to accept exploitation in the workplace.

“I just thought you had to accept it,” Bryant said. “You just had to take it because there was nothing you could do about it. But that’s what [employers] want you to think. Mama Cookie said we have to fight back to make change. Her words are strong enough to move the next generation. When I think of all the work Mama Cookie has put forth—and everything that our ancestors have gone through—there’s a debt, and we’re the generation that’s coming to collect.”

No matter what happens, Mama Cookie said the USSW has already won.

“It is a victory to have this union in the South,” she said. “When I stood there, and I saw Black, white, and Latino workers come together under one roof and say, ‘We’ve had enough,’ that meant more to me than anything. It made me feel like all my work has not been in vain.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.