Black Men in America Are Traumatized by Racism — Are We Listening?

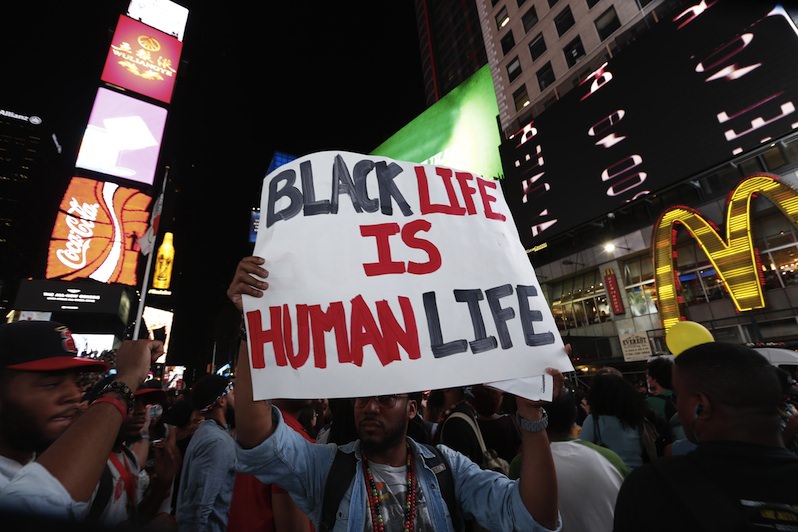

The topic of racism often generates discussions of justice, equality, freedom and human rights. But what about trauma? Protesters march in New York City on Aug. 14 to demand justice for the police-related deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Shutterstock

Protesters march in New York City on Aug. 14 to demand justice for the police-related deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Shutterstock

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a two-part series about the impact of racism on African American men. Click here to read the first installment.

The topic of racism often generates discussions of justice, equality, freedom and human rights. But what about trauma? Although trauma is often accepted as a predictable outcome of war, physical and sexual abuse, and witnessing violence, racism is only recently being viewed as a cause of trauma.

In an earlier column, based on conversations I had with three friends — Jon, Mark and Hop — who are black men, I shared the racial animosity they faced on a daily basis. Their experiences are typical of most black men. But it is just as important to consider how racism impacts their mental health as it is to confront the cause of their suffering.

My conversations with all three men left me shaken for days, as I turned over and over in my mind what it might feel like to have guns trained on me by uniformed cops multiple times in a lifetime, starting sometimes from childhood. What must it feel like to be routinely handcuffed on a sidewalk or slammed into the back of a patrol car for no good reason? What must it feel like to worry about my child surviving an encounter with police? What must it feel like to simply be treated with suspicion at every turn? Even thinking about these questions conferred on me a sort of secondary trauma.

Jon told me he has often wanted to ask cops, “Why do you hate me? Why would you hate me? I weigh 140 pounds. I’m one of the skinniest people I know. Why would somebody look at me like I’m a threat?”

“It’s really hard to deal with,” he said shrugging, “but who really has a choice?”

Hop confessed, “It’s very painful. It’s taxing, it’s emotionally draining and it’s spiritually debilitating to have to deal with this all the time.”

We expect black men to simply accept the horrors of racism, to internalize it and not express rage or frustration. Jon told me, “For the average black guy, there’s this anger, and fear, and nervousness when they’re around the police. And police pick that up.” He raised a hypothetical scenario: “If you pull over four black guys in a car, well, one out of four black guys maybe just is going to feel like he’s had enough. Maybe he’s not going to do anything violent. Maybe he just wants to be mad about it. Just to be angry. Just to show his anger.”

Hop deals with it in different ways. For example, he feels he is a lot more gregarious than he would be if he were not black. “When I’m in an elevator, I speak to everybody. Because I know that there’s a narrative out there about being in an elevator or in enclosed spaces with a black man. I try to be friendly in those environments … so that it interrupts those narratives.” He admits that it gets tiring to have to do that on a constant basis.

Even more disturbingly, Hop fears being alone with white people:

I’m not going to be alone with white people that I don’t know because I’m concerned about what could happen based on that. In particular a white woman — I don’t want to put myself in a position of being alone with them without any witnesses because I know historically how that’s played out for black men.

Jon expressed his frustration to me, saying, “You’re trying to do the right thing all the time but you’re still being treated like you’re not. You’re still being viewed like you’re the criminal. Ladies grab their purses. The police show up in these weird situations and they’re always going to handcuff you.”

Mark told me the problem is so widespread he can’t let it get to him. “At a certain point you just have to be realistic about it. You have to understand really early on that it’s not something intrinsically wrong with you.”

I asked Mark about his 13-year-old son Miles, a tall young man with chocolate skin and long hair similar to his father’s. How did Mark deal with the fact that his son was surely having experiences with people and the police similar to his own? It is a testament to the societal violence young black men routinely face that their parents feel compelled to have “the talk.” “The talk’s been going on for a long time now,” Mark said quietly. “It’s a difficult thing to navigate because we know a child shouldn’t have to deal with this.”

Mark emphasized the importance of making clear to his son not to internalize racism, telling Miles, “This is society’s issue; this is something that you didn’t bring on yourself. But just because you didn’t bring it on yourself doesn’t mean you can ignore it. You have to survive so you can see things change.”

Survival is a key factor in these discussions of racism. Hop told me he harbors a fear every single day that he could die. “I know every day that I leave my house to go somewhere … from the moment I leave my house, that there’s a good chance if I run into law enforcement that I may be dead. I know that every day.” He added, “To live with that reality on a day-to-day basis is very painful.” I found that even talking about the experiences was painful. “It’s really difficult to talk about this, isn’t it?” I asked Jon. “We don’t talk about it enough, do we?” He replied, “No, and if I don’t have to, I don’t.” He went on to acknowledge the shame that is often generated from racist encounters by the victims themselves:

Most of the people that are trapped in these horrible situations have a hard time not believing that it’s their fault. And everything on television tells you it’s your fault. There’s so much to make you believe that it’s all your fault and you should just shut up and not think about it.

All three men I spoke with said the pain runs deep. We know that there are long-term health impacts from having constant emotional trauma. If experiencing racism on a consistent level causes the type of emotional trauma that these conversations with black men have revealed to me, how debilitating could they be on long-term physical and mental health?

Black men, who have the lowest life expectancy rates of any demographic in the U.S., suffer from higher than average rates of diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Although these disparities could be attributed to differences in income and access to health care and healthy foods, studies like this one and this one are increasingly implicating racism as a potential trigger of disease because it “acts as a stressor.”

Frequent near-death experiences and encounters with armed police can also have an effect similar to what survivors of war experience. Hop likened the impact on his psyche to that of soldiers in war:

Some of the instances that I’ve talked about, I’ve walked away shaking. Literally, physically shaking in my body because there’s so much that’s happening. Soldiers do it. When you get in these near-death experiences, that’s a medically acknowledged reaction that your body’s having. PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. … Black men have PTSD. It’s the same manifestations that happen when you leave a war-torn environment … the same realities that people of color, particularly black men, face walking through this society.

The mere fact of not being believed can also add to the trauma caused by a racist act. Jon explained that “there are a lot of situations where, regardless of how well you may do your job, how well you make speak, you just aren’t perceived as intelligent or as believable, which has an effect.”

Take the example of the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Mo., this summer. A Pew Research Center poll in mid-August found that blacks were twice as likely as whites to view the shooting as raising “important issues about race that need to be discussed.”

Hop is quick to point out that overcoming racism is “work that white people need to do with other white people … and create other white allies,” as it is a “double burden to put that on people of color.” But he did have one concrete suggestion, saying with a smile: “At Thanksgiving, when Uncle Bob says that racist thing, you need to challenge Uncle Bob.”

We need to stop denying the lived experiences of people of color, but particularly black men. When black American men are telling us that the abuse is unending, that the pain is so deep it is often unbearable, we need to listen. And we need to act. If we don’t, we are all responsible for allowing a whole segment of our society to die a little every day.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.