Billionaires in Space: Escapist Fantasies in the ‘Age of the Refugee’

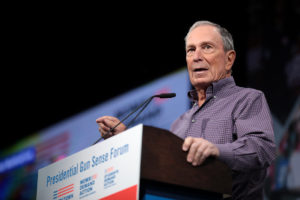

After exhausting all of earth's resources, the superrich are ready to colonize other worlds. During a 2016 media tour of Blue Origin, the space venture he founded, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos shows off a copper exhaust nozzle to be used on a spaceship engine. (Donna Blankinship / AP)

During a 2016 media tour of Blue Origin, the space venture he founded, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos shows off a copper exhaust nozzle to be used on a spaceship engine. (Donna Blankinship / AP)

“But look here, doctor,” muses President Merkin Muffley as Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove” approaches its hilarious, apocalyptic end. “Wouldn’t this nucleus of survivors be so grief-stricken and anguished that they’d, well, envy the dead and not want to go on living?” The eponymous Dr. Strangelove has just suggested a plan through which a small group of humans could survive a Soviet “doomsday machine” in “some of our deeper mine shafts.”

The doctor reassures him: “When they go down into the mine, everyone would still be alive. There would be no shocking memories, and the prevailing emotion will be one of nostalgia for those left behind, combined with a spirit of bold curiosity for the adventure ahead!” (He then, of course, gives an involuntary, if enthusiastic, Nazi salute.) He has already assured the assembled crew of national security bigwigs that our “top government and military men” would have to be included to “impart the required principles of leadership and tradition,” and he goes on to reassure Gen. Buck Turgidson, played by the inimitable George C. Scott, that this multigenerational survival plan would indeed require “the abandonment of the so-called monogamous sexual relationship”—at least “as far as men were concerned.”

Vulgar eschatology is always a survivalist fantasy. The cumulus repose of raptured souls is nowhere near as interesting as the guerrilla “Tribulation Force” who will be, in the immortal words of Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, “Left Behind.” Who, after all, is interested in the dull, leveling equality of God’s kingdom come, the want-less communism of a messianic age, when there are bunkers to defend against the starving hordes, zombie heads to be detached from their bodies and, of course, plenty of prestige-TV tits and ass?

Which brings us to the billionaires.

There is a certain apocalypticism inherent in the hoarding of extreme wealth. After a certain number of millions of dollars, every additional increment becomes little more than a hedge against the possibility of disaster. Our current richest man, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, obliquely admitted as much in a recent interview in which he talked about using his “financial lottery winnings”—credit where due, Bezos is the rare uber-capitalist who is willing to acknowledge sheer luck of the draw—to fund the exploration and colonization of space. “The only way that I can see to deploy this much financial resource is by converting my Amazon winnings into space travel.”

We must do so to escape “civilizational stasis,” by which Bezos means a sort of Malthusian energy dilemma: the whole surface of the earth covered in solar panels and still inadequate for future energy demands of the teeming masses in a century or two.

Bezos’ expressed vision is more beautiful. Our world will be “zoned residential and light industry,” the parkland Broadacre City of Frank Lloyd Wright’s imagining, with silent, autonomous, electric cars zipping us from place to leafy place.

In space, meanwhile, there could be trillions of us, including “a thousand Einsteins and a thousand Mozarts.” What, precisely, these billions upon billions (less approximately 2,000 very smart, very musical people) will be doing, or how they will afford the berth on the rocket ship on their fulfillment-center slave wage, is unclear, but, as the automated airship blares in “Blade Runner,” “A new life awaits you in the off-world colonies! The chance to begin again in a golden land of opportunity and adventure!” We already have student loans in this world. Perhaps we can revive the agreements for the new ones.

Though clothed in the language of technological utopianism, Bezos’ fantasy is an extrapolation of environmental catastrophe. As always, this is imagined as a problem fundamentally of the masses, not the masters—the barbarians at the gates, not the feckless and debauched senatorial orders running Rome into the ground. Well, what are the energy demands of a human, or a city of them, compared with Amazon’s server farms? What is Jeff Bezos’ fortune if not the burning of a zillion calories of primeval carbon to power, transaction by transaction, a mechanized, mercantile empire?

Writer and professor Douglas Rushkoff recently published an amusing but terrifying account of a sort of colloquium he conducted with a small gaggle of hedge-fund capos. Thinking he’d been hired “to deliver a keynote speech to what I assumed would be a hundred or so investment bankers,” he jets off to one of the private-resort enclaves that the very rich have built to avoid the miasmic lower orders. There he finds that his audience is, in fact, just five extremely wealthy men, and for “half [his] annual professor’s salary ,” he entertains their questions about survival after The Event. “That was their euphemism for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus or Mr. Robot hack that takes everything down.”

Their transhumanist post-apocalypse is almost charming in its brutal mundanity: walled compounds and armed guards. They debate whether a more effective mechanism for controlling their personal militias would be food rationing or explosive discipline collars. Rushkoff does not mention any consideration of where the food to be rationed would come from. This may be an oversight in the telling of the tale, but I like to imagine they picture a fortified Whole Foods in the middle of this blasted landscape, from which they might from time to time restock their safes. When Rushkoff suggests—I like to imagine a Spock-like arched eyebrow—that they might consider starting now by cultivating close, equitable relationships with their retainers (i.e., that they might simply treat their servants decently), they brush him off as hopelessly naive.

These fantasies of escape are an interesting piece within the dominant political strain of neoliberalism over the last 50 years or so, which is at its heart an unshakable commitment to the belief that things cannot ever get better, at least for most of us. It is, in effect, the belief that debts in the present foreclose the possibility of a future, at least as far as the bulk of the species is concerned. It can conjure up individual trillionaires within our lifetimes, but it can’t believe that for the development costs of a single line of fighter jet that can’t take off in the rain, we could send everyone to college for free. We can have employment, or we can do something around the margins of climate change, but not both. Collective action is impossible, and popular politics are deeply suspect.

But the billionaires’ dream does infect the slightly less fabulously wealthy, the mere millionaires who make our laws, run the day-to-day of our businesses, operate our insurance firms, believe they got it all through the sweat of their brows. They think Jeff Bezos is going to take them along.

In the third season of Noah Hawley’s “Fargo”—a clever homage that we might, in this Disney-dominated era, say exists in the same “cinematic universe” as the Coen brothers’ original film—a rich but hapless parking-lot magnate played by Ewan McGregor is drawn into an elaborate corporate credit fraud by a mysterious villain played with unctuous, disheveled malice by David Thewlis. At first resistant to the funny business, McGregor’s Emmit Stussy finds himself slowly drawn in as Thewlis’ Luciferian pitchman paints a dire picture. “We live in the age of the refugee, Mr. Stussy,” he intones. He warns of “pitchforked peasants” who will soon descend when they realize that “you’ve got all their money.” And he warns that Stussy is not really rich. Rich, he explains, “is a fleet of private planes.” It is a “bunker in Wyoming and one in Gstaad.” He cajoles the dumb Stussy into making him a partner, and when he congratulates Stussy and himself on being in business together, Stussy asks, almost plaintively, what business is that?

“The billionaire business,” Thewlis replies, and the bare hint of a grin teases McGregor’s face. Only too late does he realize that he is not a partner at all. He’s something halfway between livestock and well-trained serf.

I do not think Jeff Bezos is deliberately villainous in the manner of a TV bad guy. That’s one of the problems with real life: A lot of our enemies believe in LEED-certified buildings and gay marriage. But he does view humanity, especially human labor, as a resource to be extracted and burned, never mind the global consequences.

The market is like the climate, and whether or not humans bear some ultimate responsibility, it operates inexorably, obeying only natural law, and there is bound to be a scramble for the high ground as the waters rise.

Bezos needs to mine just enough of the market to build himself his rocket ship, or at least his bunkers. Several thousand transnational billionaire brothers (the sisters are rare) share this view. They have won the lottery, and they intend to abscond with their winnings.

They will not make it into space, but their fleets of private jets and their walled, fortified compounds already exist.

To update Rosa Luxemburg: “Society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into feudalism.”

Which would you prefer?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.