Beyond Boko Haram: Long-Term Justice for Nigeria Lies in Economic Empowerment and Social Change

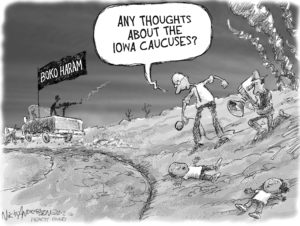

Although an international campaign drawing attention to the hundreds of kidnapped girls this past April under the social media banner of #BringBackOurGirls has gathered serious momentum, little attention has been paid to the conditions that have nurtured a group like Boko Haram.Although an international campaign drawing attention to the hundreds of kidnapped girls this past April has gathered serious momentum, little attention has been paid to the conditions that have nurtured a group like Boko Haram.

People attend a demonstration calling on the government to rescue the kidnapped girls of the government secondary school in Chibok, in Abuja, Nigeria, on May 22. AP/Sunday Alamba

Nigeria is unraveling.

And it is not just because young girls and women are being disappeared in broad daylight by the militant group Boko Haram, whose name translates to “Western education is an abomination.” It is not simply because the same group has also killed hundreds of Nigerians in raids in just the past few weeks with complete impunity.

Although an international campaign drawing attention to the hundreds of kidnapped girls this past April under the social media banner of #BringBackOurGirls has gathered serious momentum, little attention has been paid to the conditions that have nurtured a group like Boko Haram. Nigeria is a global energy center and the source of major profits for multinational oil companies, yet ordinary Nigerians hardly see the benefits of their nation’s resources — a fact that plays directly into the discontent that Boko Haram harnesses. A corrupt government that pays lip service to Western militarism while quietly appeasing rebel groups is also a part of the equation of harm that has resulted in Nigeria’s unraveling.

Dele Aileman, a Nigerian born journalist and international labor campaigner (and a personal friend), has been observing the situation unfolding in his homeland from his current base of Los Angeles. In an interview on Uprising, he told me that what Boko Haram has done “is completely condemnable. There is no way it can be defended. Yes, they want to discourage Western education which they think is corrupt and corrupting to Islamic values, but that is their own insane interpretation of the sacred Islamic texts.”

For Aileman, this is personal. The conflict in Nigeria is often presented through the rubric of the Muslim-dominated north fighting the Christian-dominated south. But Aileman, speaking to me “as the son of a Christian church minister from the South,” dismissed this lens as “completely untrue.”

Aileman thinks that the corporate media’s interpretation of Boko Haram as driven primarily by an extremist Islamic ideology is far too limiting. To him, the social and economic context is just as important. The group has its origins in what he called “social agitation” in the northern parts of the country where “the government is not considered legitimate.” In fact, he told me, “the fighters are Nigerians fighting for their daily existence like the rest of us.” He maintained that the Borno State in the northeast of Nigeria where Boko Haram is headquartered is an area where the central government has almost no presence, where the youth unemployment rate is sky-high, and whose residents live on about 40 cents (U.S. dollar) per day. In parts of that state, hundreds of thousands of poor children study in Islamic schools that are similar to Pakistan’s madrassas. “These are easy recruits for groups like Boko Haram,” Aileman lamented.

The other part of the equation in Nigeria’s unraveling is the link between the government and Boko Haram. Former President Olusegun Obasanjo, who has been implicated in serious cases of corruption and abuse, is attempting to negotiate with Boko Haram over the abducted girls. But an incident during negotiations in 1999 under Obasanjo’s leadership resulted in the death of one of the group’s leaders, which led to anger toward and mistrust of the current government.

The administration in place now under President Goodluck Jonathan is hardly an improvement. Aileman dismissed it as “nothing but a kleptocracy” that has “formed very unholy and dirty alliances with multinational companies and the captains of capital around the world.”

Still, a level of dependency between the government and the militants remains. Aileman said, “Boko Haram could not have been carrying out the daring attacks that they have been engaged in, without the local support of the people, including some leading local politicians.” That is why, he added, “some of the politicians cannot face them to condemn what they are doing now.” In fact, those same political forces are expecting to turn back to Boko Haram for support during the next round of elections.

Boko Haram even has some support from elements of the Nigerian military. The village of Chibok, where the young girls were snatched, was apparently under a state of emergency when the abduction took place. “How could that have happened,” Aileman asked, “if there was a heightened alert by the security agencies to make sure this kind of thing does not occur?”

The most important variable in Nigeria’s mess that gets the least attention is the role of the U.S. in the country. President Obama has deployed 80 U.S. troops to the region to help retrieve the kidnapped girls, and some news reports point to the possibility of attacks by militants on “U.S. interests in Nigeria.” Aileman told me, contrary to that, “Boko Haram is really focused on attacking Nigerian security installations and military barracks.” The kidnapping of the girls was out of the ordinary compared with the standard operations it carries out. “Every government in Africa will say, ‘we are facing terrorist threats.’ But once you invoke the term ‘terrorism,’ of course the U.S. will come,” Aileman said. He likened the news reports of imminent threats to what the media did under the Bush administration before the Iraq War: “They are heating up the political temperature.” Threats against Western interests by Boko Haram, if they are even true, would have materialized only after a show of force by Western countries such as the U.S. and some European nations. In fact, France’s recent move to gather the leaders of five West African countries in Paris was similar, according to Aileman, to a “classic performance of a neocolonial tragic drama.”

So angered was Aileman by the meeting that he remarked it was “almost redolent of the 1884 Berlin conference where African leaders had to go and genuflect, when Otto Bismarck split up Africa. It is a shame that at a time when we are celebrating for the first time in 520 years the political independence of the whole of Africa, African leaders have to go to Paris to discuss such a crucial matter.”

The phrase “Western interests in Africa” translates into the reaping of huge profits by Western and transnational companies off of the continent’s vast natural resources. In Nigeria, the prize is oil, an industry that enriches companies like Shell Oil at the expense of the majority of ordinary Nigerians. But constant threats of violence in and around oil operations are considered “bad for business.” Does the U.S. really benefit from political and military instability in Nigeria? Aileman responded, “It is a dilemma for them” because “I understand that when it comes to protection of sources of oil people get very desperate. They want to jump on it quickly.”

The major source of Nigeria’s oil is not located in the north, where Boko Haram is active; rather, it is in the Niger Delta. But by invoking the “terrorist” threats of Boko Haram in Nigeria, al-Shabab in Somalia and al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, the U.S. sees an opportunity to create an “African High Command” in parts of Africa and justify the existence of the current U.S. Africa Command. Although former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in her new memoir, “Hard Choices,” claimed, “Unlike in Europe and Asia, the U.S. military footprint in Africa is nearly nonexistent,” investigative reports reveal quite the opposite.

Unfortunately the well-being of ordinary Nigerians is not now, and has never been, the U.S.’ concern. When President Obama was first inaugurated, his Kenyan heritage led many Africans to believe that a new era in U.S. relations with African countries would be launched. Instead, he has simply continued Bush-era policies, even escalating military actions through drone strikes in countries like Somalia. Aileman said, “I will leave President Obama to stand before the jury of history.” His voice cracking, he added, “Africa has been pushed to a darker path than it was before he became president.”

The “terrorism” argument, which justifies Western military presence, ensures that Nigerian oil continues to funnel profits into corporate coffers. In the meantime, hundreds of young girls and women remain missing, leaving behind brokenhearted families.

When I asked Aileman what he made of the #BringBackOurGirls campaign and its success in drawing international attention to the kidnapped girls, he remarked, “Hashtag activism is good, but it is not enough.” Instead Aileman, who is organizing a “World African Conference,” wants to bring people of African descent together to move beyond the conversation of dealing with terrorism to taking on “the more profound questions of economic and social deprivations that people are facing.”

According to Aileman, “there will be no long term and sustainable solution to the problem of Boko Haram and the general unraveling of Nigeria until and unless the major grievances that spawned the problems in the first place are addressed.” That means extended economic and social justice.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.