Beware the Hero Worship of John McCain

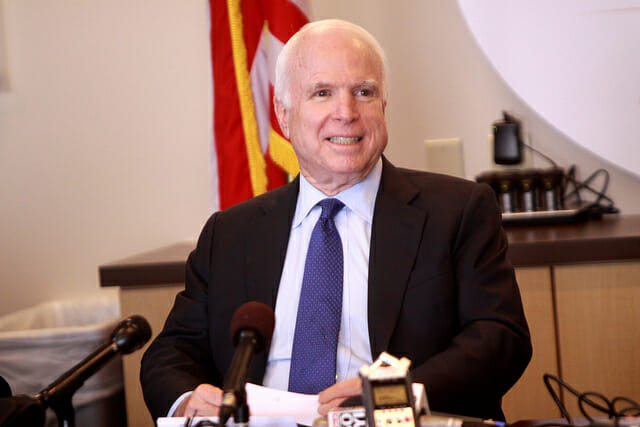

As a prisoner of war, he passed horrendous tests. But later, tested in the Senate, he often failed monumentally. Gage Skidmore / Flickr

Gage Skidmore / Flickr

In early 1973, I was a precocious, impressionable 11-year-old, the son of a career Air Force officer, growing up on Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. The Vietnam War was a constant reality—my father had done a tour there in 1967, and my uncle followed in 1970 as an infantryman who participated in the invasion of Cambodia. We lived close to the main runway, and every day scores of fighters, bombers and transports flew over our home, transiting to Vietnam or back to the mainland United States. When President Nixon announced that there would be “Peace with Honor” on Jan. 23, 1973, I saved the front page of the Honolulu Star Bulletin as a memento of that auspicious occasion.

Everyone affiliated with the armed forces at that time found the ordeal of the men being held captive in Southeast Asia to be ever-present, as did I. Like most of my peers, I wore a bracelet bearing the name of one of the prisoners of war, or POWs (an act made even more cool to a youngster by the fact that my hero at the time, John Wayne, also wore one). One of the conditions of the cessation of hostilities was the return of the American prisoners, and when it was announced that they would be transiting through Hickam Air Force Base on their way home, I made my mother promise we would meet every single aircraft to greet the returning heroes and, if circumstances warranted, allow me to personally give my bracelet to “my” prisoner.

My mom was true to her word—no matter the hour, she would gather me up and take me to the Military Airlift Command (MAC) terminal, where together with scores of others we would gather behind chain-link fences to wave and cheer as the POWs stepped off the aircraft. Such was the case on March 16, 1973; my mom pulled me out of school, packed me up in the family car and drove to the MAC terminal, where we watched the POWs deplane.

One returning prisoner stuck out among the others that day—a Navy lieutenant commander named John Sidney McCain III. My mom pointed him out, but he wasn’t hard to miss—a broad smile and a head of grey-white hair helped him stand out as he waved back at us. I knew his story: The son of the commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific, shot down over Hanoi, McCain had refused an opportunity to return home early, opting to remain a POW until all his fellow prisoners were released. I waved especially hard as McCain walked past, certain as only a kid my age could be that he was smiling and waving back at me personally.

A little more than a quarter century later, on Sept. 2, 1998, I had the opportunity to relay this story to now-Sen. McCain in his Senate office. I had been invited to meet with the senator on the eve of my testimony before a joint session of the Senate Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees concerning Iraq—specifically inspections and weapons of mass destruction—following my resignation a few weeks earlier from the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), where I had served for seven years as a senior weapons inspector.

In the intervening time I, like many Americans, had become familiar with the complexities surrounding McCain, from his role in the Keating Five scandal of the late 1980s (McCain was eventually cleared of any wrongdoing) to the portrait of his life provided by Robert Timmer in his book, “The Nightingale’s Song.” To me, John McCain was an American hero, and to have the opportunity to meet with him was, at the time, the honor of my life.

Our meeting was rushed—McCain had little time to listen to my reminiscences. My appearance before the Senate was creating a political firestorm for the Clinton administration, and McCain, ever the politician, was keen to position himself to take advantage of it.

In telephone calls with McCain’s staff leading up to the meeting, my unofficial “handler,” a New York City lawyer named Matthew Lifflander (the father of a good friend, Justin, who had worked with me implementing arms control in the former Soviet Union), had relayed some of the more critical areas of concern regarding Iraq’s noncompliance with its obligation to disarm, including intelligence relayed to me by Dutch security services about components for three nuclear devices that were alleged to still be in the possession of the Iraqis. McCain had seized on this piece of information, asking repeated questions about the sourcing of the intelligence, and who—if anyone—in the U.S. government knew about it.

I answered his questions completely and honestly—the source was an Iraqi security official who had defected to the Netherlands and was under their control; that other information provided by this defector had been shown to be accurate; that the CIA was aware of this information through liaison with the Dutch; and that I had inserted this intelligence in a report that was turned over to U.S., British and Israeli intelligence services, all of which treated it as actionable. I also told the senator this was very sensitive information, and to the best of my knowledge it was still being investigated by both UNSCOM and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The political fireworks McCain had anticipated for the hearing were quite real—it turned out that the hearing was able to go forward only because the Republican majority leader, Trent Lott, had put the Senate into recess to overcome Democratic objections to it taking place at all. And while most of the senators asked questions that were respectful in tone, Delaware’s Joe Biden did not, choosing instead to lecture me on operating “slightly above my pay grade,” saying that’s why the people empowered to make these decisions “get the limos and you don’t.”

I will forever be grateful to McCain for his response to Biden’s barbs. “I want to say, Mr. Ritter,” McCain stated when it was his turn to ask questions, “that I appreciate your courage. I appreciate the fact that you’ve given up a very important position because you felt that your obligation is to the American people. And some of us who fought in another conflict wish that the Congress and the American people had listened to someone of your pay grade during that conflict, and perhaps there wouldn’t be quite so many names down on the wall. So we appreciate the fact that someone of your pay grade would be willing to come forward with this vital information.”

McCain then went on to ask pointed questions about the policies of the Clinton administration when it came to disarming Iraq, saying that “the unfortunate aspect of this, and perhaps one of the motivating factors in moving forward, is the United States articulating one policy when in reality they are doing exactly the opposite? Isn’t that the problem here?”

I answered in the affirmative, to which McCain responded, “And that’s what’s disturbing to so many of us. Seven months ago, the secretary of state threatened force if these inspections weren’t allowed to be completed. And now, apparently, from [yours] and other evidence that we have, the secretary of state is arguing against the completion of the inspections. I’d like to get back just for a second to the gravity of this situation. Do you believe that Saddam Hussein today has three nuclear weapons assembled—lacking only the fissile material?”

I had not expected this question, having told McCain of the sensitivity of the source. But now I had to answer, or else look the fool. “The Special Commission has intelligence information,” I said, “which indicates that components necessary for three nuclear weapons exist, lacking the fissile material.” I went on to explain that this did not mean Saddam Hussein had a nuclear capability, noting that because of the success of the IAEA in dismantling Iraq’s indigenous nuclear enrichment program, total reconstruction would take years to complete. I also pointed out that a political decision would have to be made by Saddam Hussein for the clock to start ticking toward rearmament.

McCain cut to the chase. “So it is your opinion that if these inspections are further emasculated, then within a six-month period of time, Saddam Hussein would have the capability to deliver a weapon of mass destruction?”

“Yes, sir” was my reply.

The truth was far more complicated, and nuanced, than that. The operative word “would,” was in fact, more accurately, “could.” I take responsibility for failing to correct his question at the time, and it was a glaring error on my part—the headline from my testimony was that Saddam Hussein was six months away from having a deliverable weapon of mass destruction which, by inference, could include a nuclear device. This was not what I testified to or believed to be the case. But it was now how the public perceived my position.

I left the hearing more than a little upset with McCain and his staff. The meeting on Sept. 2 had led me to believe that the senator was going to focus on policy issues, and not delve into the issue of specific intelligence about what we, as inspectors, were looking for. I felt that McCain had asked the question about the nuclear devices for the sole purpose of getting this information into the public eye, leaving me to deal with the consequences. This was my first foray into the rough-and-tumble world of national politics, and I didn’t like it one iota.

McCain got his wish—the story about Iraq’s nuclear devices got a lot of attention. The Clinton administration responded by stating that I had made the whole thing up, and that it had never been told about such information. I fully expected McCain, having let the cat out of the bag, to come to my defense, but he remained silent.

Left with little choice, I approached The Washington Post, and provided one of its investigative reporters, Barton Gellman, with documents and enough specific information to back up my claim. In a front-page story published on Sept. 30, 1998, Gellman reported that U.S. intelligence officials, reversing their earlier denials of my testimony, now concurred “on the credibility of the reports” which detailed Iraq’s possible retention of the components for three to four “implosion devises” without the fissile core, and acknowledged that UNSCOM had, in fact, brought the information about the nuclear components to their attention, once in 1995 and then in 1996.

In December 1998, while in New York City to help publicize a cover story on Iraq I had written for The New Republic, I ran into McCain in the lobby of 1 Union Square West. He was cordial, asking me how things were going. I took the opportunity to tell him that the Iraq issue wasn’t black and white, and that if the United States wasn’t careful it could find itself in a war that didn’t need to be fought.

“The important issue is to fight for the integrity of the inspection process,” I told him. “We need inspectors to investigate information on whether Iraq actually has components for a nuclear device. But the fact that we are investigating doesn’t mean that these components in fact exist. Intelligence can be wrong, and often is.”

McCain was distracted and eager to get on with his schedule. He shook my hand. “Call my office,” he said. “We will schedule some time to talk.”

Over the course of the next three years, I made that call many times. The senator and I never had that talk.

In July 2014, McCain told CNN that his military background would have allowed him to “have challenged the evidence with more scrutiny,” noting that he hoped he “would have been able to see through the evidence that was presented at the time.” Calling the evidence of Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) “very flimsy,” McCain stated that “it’s obvious now, in retrospect, that Saddam Hussein—although he had used weapons of mass destruction—did not have the inventory that we seem to have evidence of.”

This statement is ironic in that McCain was one of the foremost supporters of military action against Iraq. I was a supporter of McCain’s 2000 bid for the Republican nomination for president but continued to be frustrated by his statements on Iraq. When McCain bowed out of the race on March 9, 2000, I reached out to him and a number of other senators, including Chuck Hegel and John Kerry, about holding hearings in an effort to try and rein in the rush toward war with Iraq. Both Hegel and Kerry told me to “put my concerns in writing” so they could consider them more carefully; McCain never responded.

In June 2000 I published an article, “The Case for Iraq’s Qualitative Disarmament,” in Arms Control Today. The publisher, at my request, sent a copy to every senator and representative in Congress. In this article I provided a detailed debunking of the intelligence underpinning claims that Iraq continued to possess WMD.

Iraq has not fully complied with the provisions of Security Council Resolution 687. On this there is no debate. However, this failure to comply does not automatically translate into a finding that Iraq continues to possess weapons of mass destruction and the means to produce them. Resolution 687 demanded far more than the dismantling of viable weapons and weapons-production capabilities. Most of UNSCOM’s findings of Iraqi non-compliance concerned either the inability to verify an Iraqi declaration or peripheral matters, such as components and documentation, which by and of themselves do not constitute a weapon or program. By the end of 1998, Iraq had, in fact, been disarmed to a level unprecedented in modern history, but UNSCOM and the Security Council were unable—and in some instances unwilling—to acknowledge this accomplishment.

I followed up this article with yet another outreach to McCain, to no avail. Regardless of what he said in 2014, there is no doubt in my mind that McCain had made up his mind about the threat posed by Iraq, and that had he been elected president, he would have followed the same path as George W. Bush in invading and occupying that country.

Contrary to his claims of being able to see through “flimsy” intelligence, McCain supported even the wildest conspiracy theories about Iraq and WMD. For example, on Oct. 18, 2002, he went on “The David Letterman Show,” where he had the following exchange with the host about a series of incidents involving the delivery of powdered anthrax, a biological agent, via the U.S. mail to a number of high-profile personalities:

Letterman: “How are things going in Afghanistan now?”

McCain: “I think we’re doing fine … I think we’ll do fine. The second phase—if I could just make one, very quickly—the second phase is Iraq. There is some indication, and I don’t have the conclusions, but some of this anthrax may—and I emphasize may—have come from Iraq.”

Letterman: “Oh, is that right?”

McCain: “If that should be the case, that’s when some tough decisions are gonna have to be made.”

On that same day The Guardian published an op-ed I wrote titled “Don’t Blame Saddam for This One: There is no evidence to suggest Iraq is behind the anthrax attack.” I detailed the scientific and political reasons why the effort to pin the anthrax attacks on Iraq were wrong, noting that “Washington finds itself groping for something upon which to hang its anti-Saddam policies and the current anthrax scare has provided a convenient cause. It would be a grave mistake for some in the Bush administration to undermine the effort to bring to justice those who perpetrated the cowardly attacks against the U.S. by trying to implement their own ideologically-driven agenda on Iraq.”

I sent this op-ed along to McCain’s office, along with a request to meet and discuss the matter. There was no response.

The Iraq War turned out to be one of the greatest mistakes in American history, something McCain came to realize in the twilight of his career. “The principal reason for invading Iraq, that Saddam had WMD, was wrong,” McCain wrote in his last book, “The Restless Wave,” published this May. “The war, with its cost in lives and treasure and security, can’t be judged as anything other than a mistake, a very serious one, and I have to accept my share of the blame for it.”

With age comes reflection, and from reflection wisdom. In the end, John McCain emerged as the wise old man of the Senate he always aspired to be—at least on the issue of Iraq. The same level of reflective intuition seemed lacking on other issues, such as Ukraine, where McCain favored a more robust response to Russian actions, and Syria, where the Arizona senator favored decisive military intervention to remove Syria’s president, Bashar Assad, from power. Iran, too, brought out the military adventurist in McCain, with him famously channeling the Beach Boys in singing, “Bomb, bomb, bomb, bomb” Iran.

I can’t claim to have the level of insight into the formulation of McCain’s thinking when it comes to Ukraine, Syria and Iran. What I can say, having had the benefit of the same regarding Iraq, is that his thinking was fundamentally flawed, a knee-jerk reaction designed to please a political base that had little true regard for the lives and welfare of the military men and women who would be called upon to pay the price in blood, and the American taxpayer who would have to underwrite the cost in treasure, for McCain’s hubris and political ambition. Here, John McCain was fundamentally flawed, something those who lionize his tenure as a senator would do well to reflect on least these lessons be lost to history.

I can’t define McCain’s experience as a senator to be “heroic”; indeed, my personal bias leans in the opposite direction, bitterly recalling the opportunities the self-styled “maverick” had to do the right thing and stand up for the truth about Iraq’s WMD that was his for the taking, had he just availed himself of the opportunity. Had McCain expressed the same skepticism toward Bush’s war in Iraq as he had toward Ronald Reagan’s adventure in Lebanon, where he noted before voting against a measure to extend the presence of U.S. Marines in that country that “the longer we stay in Lebanon, the harder it will be for us to leave … we will be trapped by the case we make for having our troops there in the first place.” Or had he stood up on the Senate floor and given a “thumbs down” to the Iraq War with the same vigor he displayed in challenging President Trump’s efforts to undo Obamacare, who knows what the Middle East would look like today, and how many lives—American and Iraqi—would have been spared the horrors of that conflict and its consequences.

At the same time, I do not allow my personal animosity for a man who was empowered to do the right thing on Iraq, but failed to act, to color his accomplishments in the service of his country as a naval officer. Donald Trump infamously said of McCain, “I like people who weren’t captured.” The current president was, and is, wrong to question McCain’s military service, both as an aviator and POW. This doesn’t mean McCain was perfect—far from it.

Questions remain about aspects of his service that will be left to the vagaries of history to unravel. In this, he is the quintessential American hero—flawed, complicated, compelling.

The fact remains that John McCain was put through the kind of gut-wrenching test that few who enter military service experience, or, if they do, survive. And he passed this test with flying colors. Let no one ever doubt McCain’s mettle as a man—while a prisoner of war, he proved he had what it takes to do the right thing when the chips were down. And it is for this reason that, in remembering the legacy of this man, I choose to reflect not on his shortcomings as a senator, but rather to reflect on that day back in March 1973 when I waved frantically toward the white-haired man limping across the tarmac, hoping he could see me, and praying that someday I would be able to serve my country as honorably as he did. I’m still trying.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.