Below the Safety Net

The courageous people who work day and night in overcrowded urban emergency wards are forced to confront society's failures.

Some of the nation’s most courageous people are those who work day and night in overcrowded urban emergency wards and trauma centers. Among the patients they serve are often-dangerous gang members brought there from their impoverished and violent neighborhoods, wounded, sometimes near death.

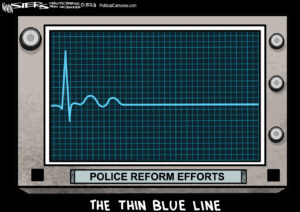

These health care workers bear the brunt of many terrible aspects of our political, criminal-justice and economic systems. A poorly funded and overtaxed health care system overcrowds the hospitals. A police, prosecutorial and court system oriented toward imprisonment builds up gangs, rather than reducing them. Schools often fail to give students the education they need to leave the dead-end gang life. High unemployment, with employers unwilling to hire ex-cons, is a constant. The frustrations from all this add to the tensions of big-city emergency rooms, trauma centers and intensive care wards. Welcome to this little-noted but reflective side of American society.

“I have seen so many homies die in ICU,” said Mike Garcia, a former gang member who works at White Memorial Medical Center, a nonprofit hospital in Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights section, to prevent violence by gang members. There are 65 gangs in the area. “Some of [the members] are 15 years old. They haven’t even graduated. They are in and out [of consciousness in the emergency care unit], tubes in their mouths. I have sat with mothers for hours, not even saying anything. Sometimes that’s their only son, their only kid. If that kid dies, they don’t have anyone in the house. They invite me to the wake, just because I sat there.”

I met Garcia while reporting on the Advancement Project, which is trying to reduce violence in gang-ridden neighborhoods. “I grew up in Boyle Heights and belonged to a gang there,” he told me. He quit when he was 40. “My sons started going to prison,” he said. “I realized that I was a bad example, so I decided to change my life and do something with the remaining years I have, something positive.”

He became part of the White Memorial staff, assigned the difficult job of defusing situations familiar to emergency room workers in gang-heavy neighborhoods across the country. When a wounded gang member arrives at a hospital, family members and fellow gangsters, all highly emotional and sometimes armed, often accompany him. At times, the victim’s enemy comes to the hospital to finish the job.

On a recent day, Garcia was teaching a class at the Advancement Project’s Urban Peace Academy. There, ex-gang members, including some who have done long stretches in state prison, are trained to intervene between violent and feuding gangs in the Los Angeles area’s poor neighborhoods. About 20 men and women listened to Garcia explain what he does.

He recalled when he was wounded, treated with disrespect by doctors, nurses and other personnel because he was a gang member. “I remember how I was mistreated when I went into the hospital,” he said. “My goal is to show the doctors and nurses that gang members are human, and there is someone there who cares about them.” He also shows the medical personnel ways of defusing explosive situations.

He is on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. He keeps an eye on the hospital parking lot and waiting room for gang members ready to continue a battle inside. He watches for family and friends ready to take out their anger on nurses and doctors. He roams the streets, fishing for information on gang and neighborhood tensions. He looks for signs that hospital visitors are packing guns or knives.

“And if [the gang members] need some kind of help getting back into school, getting a job, talking to their parents, I’m there for them,” Garcia said. “And if they are not ready to change, I tell them I’ll be here when you are.”

I asked if he was successful in getting gang members to turn their lives around. “Not as much as I would like,” he said. “They have to go back to that same neighborhood.”

Even when they are successful, programs such as this can do only so much.

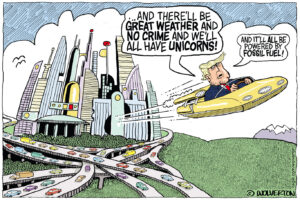

More is required than a deadlocked government and indifferent business communities will provide. First of all, we need more money for schools. In California, the schools serving kindergarten through 12th grade are so short of funds that some of them are threatening to reduce the school year. At the state universities, tuition is rising sharply, touching off student demonstrations. The curse of the 1978 tax-limiting Proposition 13 continues.

Aside from more money for education, we need a reversal of arrest and sentencing policies, reducing the number of drug — especially marijuana — arrests. These arrests load up the prisons. And finally, we need Congress, President Barack Obama and business leaders to create jobs that can be filled by those who have the least job skills.

That’s asking for the unlikely or impossible. While we’re waiting, we’ll have to be satisfied with the brave efforts of health workers and people like Mike Garcia in the trenches who deal with society’s failures without much help.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.