Batman in a Hospital Bed

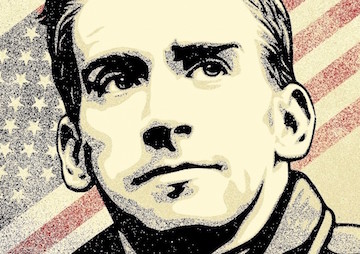

With Memorial Day in the rearview mirror, many Americans have already stopped thinking about our wars and the casualties from them for another year. As for me, it’s been Memorial Day ever since I first met Tomas Young. Detail of the cover of "Tomas Young's War," by Mark Wilkerson. (Haymarket Books)

1

2

3

Detail of the cover of "Tomas Young's War," by Mark Wilkerson. (Haymarket Books)

1

2

3

Still, after Somalia, I found myself drawn to stories about war. I reread Stephen Ambrose’s blow-by-blow account of the D-Day landings, picked up Ron Kovic’s Vietnam memoir, Born On The Fourth Of July, for the first time, and even read All Quiet On The Western Front. And all of them somehow floored me. But it wasn’t until I watched Body of War, Phil Donahue’s 2008 documentary about Iraq war veteran and antiwar activist Tomas Young, that something seemed truly different, that I simply couldn’t shake the feeling it could have been me.

Tomas was a kid who had limited options — just like me. He signed up for the military, at least in part, because he wanted to go to college — just like me. Yes, just like so many other kids, too — but above all, just like me.

He, too, was deployed to one of America’s misbegotten wars in a later hellhole, and that’s where our stories began to differ. Five days after his unit arrived in Iraq — a place he deployed to grudgingly, never understanding why he was being sent there and not Afghanistan — Tomas was shot, his spinal cord severed, and most of his body paralyzed. When he came home at age 24, he fought the natural urge to suffer in silence and instead spoke out against the war in Iraq. Body of War chronicled his first full year of very partial recovery and the blossoming of his antiwar activism.

Just a few weeks after the film’s release, however, it all came crashing down. He suffered a pulmonary embolism and sank into a coma, awakening to find that he’d suffered a brain injury and lost much of the use of his hands and his ability to speak clearly. The ensuing years were filled with pain and debilitating health setbacks. By early 2013, he was in hospice care, suffering excruciating abdominal pain, without his colon, and on a feeding tube and a pain pump. Gaunt, withered, exhausted, he continued to agitate against America’s never-ending war on terror from his bed, and finally wrote a “last letter” to former President George W. Bush and former Vice President Dick Cheney, airing his grievances, which got significant media attention.

When I read it, I felt that he might have been me if I hadn’t lucked out in Mogadishu two decades earlier. Maybe that’s what made me reach out to him that April and tell him I wanted to learn more about what had happened to him in the years between Body of War and his last letter, about what it meant to go from being an antiwar agitator in a manual wheelchair to a bedridden quadriplegic on a feeding tube and under hospice care, planning to soon end his own life.

A Map of the Ravages of War

When I finally met Tomas, I realized how much he and I had in common: the same taste in music and books, the same urge to be a writer. We were both quick with the smart-ass comment and never made to be model soldiers because we liked to question things.

Each moment we spent together only connected us more deeply and brought me closer to the self that war had created in me, the self I had kept at such a distance all these years. I began writing his story because I felt compelled to show other Americans someone no different from them who had had his life, his reality, upended by one of our military adventures abroad, by deployment to a country so distant that it’s an abstraction to most of us who, in these days of the All-Volunteer Army, don’t have a personal connection either to the U.S. military or to the wars it so regularly fights.

A historically low percentage of our population — less than half a percent — actually serves in the military. Compare that to around 9% during the Vietnam War, and 12% during World War II. Remarkably few of us ever see combat, ever even know anyone who was in combat, ever get to hear firsthand stories of what went on or witness what life is like for such a returning veteran. Not surprisingly, America’s wars now largely go on without us. There is no personal connection. Here in “the homeland” — despite the overblown fears of “terrorism” — it remains “peacetime.” As a consequence, few of us are engaged by veterans’ issues or the prospect — essentially, the guarantee — of more war in the American future.

Tomas understood the importance of sharing the brutal fullness of his story. For him, there were to be no pulled punches. When I told him I wanted others to learn of his harrowing tale, of his version of the human cost of war, that I wanted to help him to tell that story, he responded that he had indeed wanted to write his own book. He’d scrapped the project because he could no longer write, and even Dragon voice-to-text software wouldn’t work because his speech had become so degraded after the embolism struck.

Instead, he shared everything. Tomas and his wife, Claudia, opened their lives to me. I slept in their basement. During my periodic visits, he introduced me to an expansive mind in a shrunken world, a mind that wanted to range widely in a body mostly confined to a hospital bed, surrounded by books, magazines, and an array of tubing that delivered medications and removed bodily wastes in a darkened bedroom.

“I need to be fed,” he said to me one day. “Do you want to see what that’s like?” Then, he lifted his shirt and showed me the maze of tubing and scars on his body. It was a map of the ravages of war.

He was unflinchingly honest, sensing the importance of his story in a country where such experiences have become uncommon fare. Like his comic book heroes Batman and the Punisher, he wanted to make sure that no one would have to endure what he’d gone through.

An All-Too-Real Life and Surreal Wars

Tomas Young’s war ended on the night before Veterans’ Day 2014 when he passed away quietly in his sleep. His pain finally came to an end.

The bullets that hit him in the streets of Baghdad in 2004 brought on more than a decade of agony and hardship, not only for him, but for his mother, his siblings, and his wife. Their suffering has yet to end.

Stories of the reality of war and its impact on this country are more crucial now than ever as America’s wars seem only to multiply. Among us are more than 2.5 million veterans of our recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. We owe it to them to read their accounts — and an increasing number of them are out there — and do our best to understand what they’ve been through, and what they continue to go through. Then perhaps we can use that knowledge not only to properly address their needs, but to properly debate and possibly — like Tomas Young — even protest America’s ongoing wars.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.