Banks Suspected of Racial Bias in Housing Crisis Aftermath

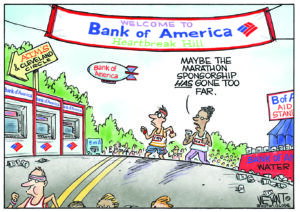

Financial institutions handling foreclosures, especially Bank of America, have been accused of letting properties in minority neighborhoods deteriorate. The National Fair Housing Alliance collected evidence that the bank is maintaining foreclosed houses in predominantly white areas in far better conditions.

Financial institutions handling foreclosures, especially Bank of America, have been accused of letting properties in minority neighborhoods deteriorate. The National Fair Housing Alliance collected evidence that the bank is maintaining foreclosed houses in predominantly white areas in far better conditions than those in nearby towns that were populated by black or Hispanic residents. The Atlantic reports on the situation, and how banks are devaluing neighboring properties by allowing the houses they own to fall into disarray:

A year ago, the alliance and several of its member organizations filed a complaint against the bank with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, arguing that the bank had violated the federal Fair Housing Act by neglecting foreclosed properties in minority communities in Denver, Atlanta, Miami, Dayton and Washington, D.C. Today, the groups amended their complaint with a stack of evidence – in maps, data, and photos – showing that the problem has persisted in each of those cities, while documenting it anew in Memphis, Denver, Las Vegas, Tucson and Philadelphia.

In total, housing advocates have now identified the problem in 18 metropolitan areas, across 621 Bank of America properties.

“It is as if Bank of America is purposefully looking the other way when they see [bank-owned properties] in communities of color,” Keenya Robertson, the CEO of Housing Opportunities Project for Excellence, said in releasing the new complaint.

Investigators with housing organizations in each city visited Bank of America-owned foreclosures in predominantly black and Hispanic zip codes in each city, as well as in predominantly white areas. They were looking for obvious indicators like whether a “for sale” sign was mounted on a property (no one will buy it, after all – or know where to make complaints about its eyesores – if they don’t know the house is for sale). But the investigators also looked for more than three-dozen individual deficiencies, including trash and mail accumulated on the curb, broken windows or locks, water damage, missing gutters, peeling paint and graffiti.

What they found: a rotting dog carcass in a Las Vegas back yard, beer bottles on the steps of an empty Denver home, and doors left wide open on a Tucson property, all in minority communities. In Memphis, none of five homes in minority communities even had for-sale signs on them. The same was true for 14 out of 15 homes in Latino communities in Tucson, and in 14 of 18 homes in minority communities in Philadelphia.

The sample size in each city varied, from about a dozen properties to more than 44 of them in Denver. But across all of the cities, homes in minority communities were two times more likely than those in predominantly white areas to have more than 10 maintenance or marketing problems. In Denver, homes in minority neighborhoods were 9.3 times more likely to have a broken door or lock. In Las Vegas, they were 4.5 times more likely to have damaged windows. In Philadelphia, they’re twice as likely to have accumulated substantial amounts of trash, relative to homes in white neighborhoods in the same market.

The pattern suggests yet another way that subtle housing discrimination may further handicap the ability of minority communities to recover from the housing crisis (or, put another way, this suggests why the effects of the recession will linger in minority communities for much longer). Federal fair housing law prohibits actions (or attempts at action) that “perpetuate, or tend to perpetuate, segregated housing patterns,” or that obstruct the choices in a community or neighborhood.

Let’s not forget that these are the same institutions that targeted minorities for high-risk subprime loans before the housing crisis.

Bank of America responded to the National Fair Housing Alliance’s well-supported complaints by trying to poke holes in its methodology and saying that the “majority of properties NFHA faulted us for were, in fact, the responsibility of other entities to maintain and market, [and] didn’t take into account the property condition at the time we had authority to maintain it. … ” The multinational went on to say that its management of bank-owned properties was “uniform” throughout, and “any suggestion to the contrary is simply untrue.”

Sounds like the bank doth protest too much.

—Posted by Natasha Hakimi

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.