‘Arrival’: A Gossamer Dream of Hope Beams In From Outer Space

It takes an otherworldly element to deliver an unforgettable moviegoing experience -- as well as a message of understanding across cultures at a time when earthlings struggle with that on our own planet.It takes an otherworldly element to deliver an unforgettable moviegoing experience—as well as a message of understanding across cultures at a time when earthlings struggle with that on our own planet.

Jeremy Renner and Amy Adams make contact with visitors in “Arrival.” (IMDb)

At first sight they look like upended dirigibles, the 12 alien spacecraft that all at once descend on six continents, hovering slightly above the ground like ballerinas en pointe.

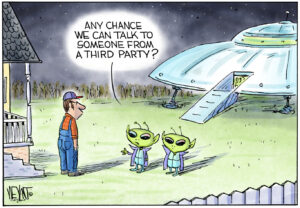

What planet are they from? Why are they here? And what gifted sculptor designed these vessels that look less like UFOs than like streamlined satellite dishes?

Not so fast. In “Arrival,” director Denis Villeneuve’s wondrous tale, before there are answers to these questions the earthlings sent to meet the visitors must first find a way to communicate with them. Unlike in kindred films such as “Contact,” “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” and—even earlier—“The Day the Earth Stood Still,” these aliens neither speak English nor learn it overnight.

As soon as the images of these otherworldly spaceships air on TV to the astonishment of earthlings the world over, Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams), a professor of linguistics, is contacted by a Col. Weber (Forest Whitaker) of the U.S. Army. Will she join the U.S. team to talk to the aliens at a remote Montana location shrouded in puffy clouds? And can she figure out what they want before another nation calls a first strike against them?

With a performance by Adams that grounds it in reality, and distinctive cinematography by Bradford Young that takes the movie to the stratosphere and beyond, “Arrival” is dreamy and moody, gossamer and opaque. It may be the most textured — emotionally and materially — film in my moviegoing experience. Even its shadows emit a glow.

And it is an experience — a privileged one, as movies of this sort often are (though not often enough: “Independence Day,” anyone?). While “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” raised theological questions and “Contact” contrasted belief in science with reliance on faith, “Arrival” is about one linguist’s belief in face-to-face communication, both the geopolitical and interplanetary kinds.

More breathless than even the well-executed action sequence is Louise’s patient contact with the extraterrestrials to answer the big question: “Why did you come?” As in Villeneuve’s “Sicario,” Louise is a solid professional, just doing her job and shrugging off the pressures of her male superiors. She is less concerned than her bosses about whether other nations have agendas different from that of the U.S. (Because they have dispatched so many ships, the aliens must know that earthlings are not exactly united.)

Louise is teamed with scientist Ian (Jeremy Renner), who believes math is the intergalactic language and is eager to ask the visitors about alien astrophysics. Louise casts a gimlet eye at him. Giving him the my-discipline-is-more-relevant-than-yours look, she observes, “First, we have to learn how to say hello.”

Because Louise lives a solitary life apart from teaching, she seems an odd choice for interstellar diplomacy. But she knows and hears the nuances of language. For example, “tool” and “weapon” might be synonymous in another tongue although they mean very different things in ours.

In their orange hazmat suits — like a knight’s protective armor or a deep-sea diver’s wet suit — linguist and physicist enter the spacecraft. What ensues is disorienting, something like the suspension and reinstatement of gravity. Directions like up and down don’t apply. We’re nervous for the earthlings because the film’s otherworldly score (by Icelandic composer Johann Johannsson) sounds like musique concrete, electro-acoustic noise of no obvious origin. Add to this the sounds of alien speech, much like those of humpback whales, and it seems Louise and Ian have entered another dimension.

It’s better not to disclose too much of what happens during Louise’s sessions with the two aliens she and Ian name “Abbott and Costello.” The visitors have both oral and written languages. The latter is like squid ink floating in liquid, forming what resemble ink-brush characters. Because Louise references the Sapir-Whorf theory, positing that the structure of a language shapes those who use it, we are primed to see Louise and Ian transformed by their conversations with these creatures.

In this year of bruising American politics, the film’s emphasis on measured communication and focused listening feels transformative as well.

The most welcome takeaway from “Arrival” is hope.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.