‘Angels in America’ Teaches Us How to Survive Under Trump

An oral history of Tony Kushner's masterwork reveals how to make political art that offers lasting solace in times of great trouble.

“The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of ‘Angels in America’ “

A book by Isaac Butler and Dan Kois

In one of my high school theater classes, our (admittedly ambitious) teacher asked me and my best friend to read a scene from Tony Kushner’s play “Angels in America.” And not just any scene: He wanted us to act out the breakup between Prior Walter, who has been diagnosed with HIV and is suffering terribly, and his lover, Louis Ironson, who is in the process of leaving Prior because his illness has become too much for Louis to handle. The assignment could have interacted badly with our heightened teenage emotional states, but instead, I remember it as a moment that deepened our friendship and began my love affair with Kushner’s remarkable two-part play.

That our teacher assigned an excerpt of “Angels in America” to public high school students in the early years of the millennium was one indicator of just how far Kushner’s play had come, from controversy to classic, since versions of it began to be performed in workshops in the late 1980s. I offer that memory not merely as an argument but as a caveat: I am, in many ways, the ideal audience for Isaac Butler and Dan Kois’ marvelous new oral history of the play, “The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of ‘Angels in America.’ ” The book will be incomprehensible to people who are not familiar with “Angels in America,” and it may not hold the interest of those whose familiarity with and interest in the play are merely passing. For those who do attempt it, though, “The World Only Spins Forward” is a vital book about how to make political art that offers lasting solace in times of great trouble, and wisdom to audiences in the years that follow.

Click here to read excerpts from “The World Only Spins Forward” at Google Books.

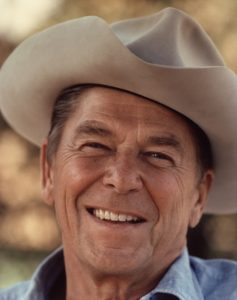

The first lesson “The World Only Spins Forward” offers artists is in creating work that is inspired by a given moment but not constricted by it. “Angels in America” is specifically about the dawn of the AIDS crisis and the ascendant Reagan revolution, but Kushner’s play treats those events as portals into larger conversations.

As Monica Pearl, a professor of English and American studies at the University of Manchester, tells Butler and Kois, it’s possible to look at the events “Angels” describes as safely in the past. But it’s also true that “AIDS exposed all the difficulties that were roiling under the surface anyway”—“homelessness, drug addiction, oppression against gay people”—and given that, it’s impossible “to relegate AIDS into history because none of those problems have gone away.”

The broader conditions that can produce a political crisis haven’t been vanquished, either. The economic conditions that formed a backdrop to the 2016 presidential election are part of a shift former Congressman Barney Frank tells Butler and Kois he began to observe in the 1970s: The loss of America’s economic position in the world primed some American voters to embrace the conservative social politics of organizations such as Moral Majority as a means of reconstituting their identity.

“Angels in America” isn’t about Trumpism, but it is about what Oskar Eustis, who helped incubate “Angels,” describes as “the life-and-death struggle of figuring out who we are” as Americans and what kind of nation we want to live in. That question is posed in different ways in different eras, but it never really goes away.

“Angels in America” is also a wonderful testament to the need to balance anger and forthright moral condemnation with other emotions, not merely as a matter of making art that feels more than didactic but as a means of survival. The play is immensely funny, a perfect example of what Princeton University assistant professor of theater Brian Herrera tells Butler and Kois is the soul-replenishing power of camp, a style of presentation that also has the ability to expose its targets as ridiculous. It’s loving, and it gives its characters room to grow: Mormon Hannah Pitt, who initially rejects her son Joe when he comes out to her, is not the villain of “Angels in America” but instead evolves to become one of its heroes. And “Angels” argues for the value of forgiving even the worst, most damaging people.

Gregory Wallace, who played the nurse Belize in a production of the show that ran from 1994 to 1995, reflected on one of the most surprising turns in the play: Belize’s ultimate goodness to Roy Cohn, a closeted gay man and one of the architects of the Reagan revolution. At a time of bitter division, that kind of thinking is often caricatured as weak or morally compromised, but Belize’s experience suggests that this sort of grace has benefits as much for the person who bestows it as for the person who receives it.

“Belize is not always very friendly but he is generous, often begrudgingly so,” he told Butler and Kois. “As our country goes off the rails, more and more so each day, I find myself asking if I am capable of that sort of generosity with the people I so vehemently disagree with. I’m not so sure, but I do think Belize is onto something when he says ‘Maybe … a queen can forgive her vanquished foe. It isn’t easy, it doesn’t count if it’s easy, it’s the hardest thing. Forgiveness.’ “

And “The World Only Spins Forward” makes the case that artists shouldn’t underestimate their potential audiences. When “Angels in America” went on national tour, there were some worries about how it would play outside coastal enclaves. But Carolyn Swift, who played the Angel in that production, found that “so many mothers would come to us backstage after the show and say ‘My son is dying,’ or ‘I just lost my son.’ We were still in the middle of the epidemic, and we were in places where those losses hadn’t been recognized.”

Not all art can be “Angels in America,” and few who aspire to Kushner’s scope will achieve the status of his masterwork. But “The World Only Spins Forward” was fascinating to me not only because it fueled my obsession but also because it helped me think about the sort of art that I crave right now: work that’s more than angry or condemnatory, work that takes the long view, work that refuses to give up hope.

“Angels in America” ends with a blessing: “More life.” In a political moment that is draining the vitality and generosity from so many of us, we need art that can give us that gift all over again.

Alyssa Rosenberg blogs about pop culture for The Washington Post’s Opinions section.

©2018 Washington Post Book World

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.