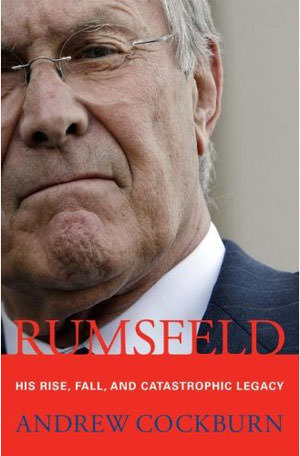

Andrew Cockburn’s Rumsfeld Revelations

The storied journalist speaks to Truthdig about his new book, "Rumsfeld: His Rise, Fall and Catastrophic Legacy," which offers fresh insight into the real force behind the Iraq debacle.

The storied journalist speaks to Truthdig about his new book “Rumsfeld: His Rise, Fall and Catastrophic Legacy,” which offers fresh insight into the real force behind the Iraq debacle.

Listen:

(running time: 29:17 / 26.8 MB)

Transcript:

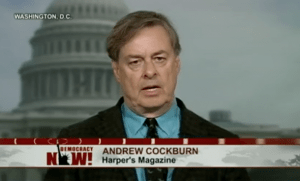

James Harris: This is Truthdig. James Harris, Josh Scheer, on the phone a man who’s written for The New York Times, The Times of London, the author of the new book “Rumsfeld: His Rise, Fall and Catastrophic Legacy,” let me welcome Andrew Cockburn to the show. How are you today?

Andrew Cockburn: Pretty good. Nice to be with you.

Harris: Now in your book you say his “rise, fall and catastrophic legacy.” In your mind what’s the most catastrophic part of his legacy?

Cockburn: The obvious candidate … the headline is Iraq … the ruin of an entire country and along with it the ruin of a good part, a good chunk, of our military and not to mention the lives and limbs of a lot of our young men and women. So, you know, that’s the obvious one, and … you know that deserves the place of, and I wouldn’t say honor, place of disgrace. But beyond that what he did was he took the whole, you know, what was already a bad situation with our military and our entire defense and made it infinitely worse.

Let me give you a couple of examples. Five years ago or six year ago when he came into power we had 80 major weapons programs, most of them designed for, to fight the Soviet Union … to fight a country that doesn’t exist anymore, [at] a total cost of $750 billion. We got the same weapons systems, no more relevant now than they were then, but now he ran the cost up to one and a half trillion dollars. That’s just, I mean that’s just part of the exploding defense budget out of control that he left us that we and our children and children’s children will be paying for for generations to come.

He brought the military into a domestic role, to a far, far greater extent than it’s ever been before. In other words we have, now we have military intelligence deeply involved in domestic surveillance, in monitoring antiwar demonstrators and monitoring progressive types. I mean it’s, we have the NSA, which is a military intelligence agency, now tapping our phones. It’s the most sinister development. And beyond that, or besides that and perhaps most horrible of all, he really institutionalized torture. I mean it’s been reined back a bit, theoretically, but he OK’d torture, he encouraged torture, he encouraged the stripping … of Geneva Convention protections from enemy prisoners. And even, as I talk about in the book, he even was practicing, or his chosen favored command within the military, Joint Forces Command, was actually practicing new refinements in sensory deprivation on an American citizen in a jail on American soil.

Harris: How do you double the military spending? You said it went from $750 billion to 1.5 [trillion dollars]. How do we trace that back to Rumsfeld?

Cockburn: Well … I mean basically, you know everyone used to say that, well, Rumsfeld … might not be a pleasant fellow, but he, at least he’s a tough, no-nonsense manager who knows how to manage the Pentagon. But as it turned out he was no such thing. … The military will always overspend, will always buy excessively complex weapons that don’t work as advertised and arrive years late and in smaller quantities than advertised. But he, by failing to administer, really administer the military at all, you know, let things run completely out of control.

So, well, let me give you one sort of prime example. There’s a weapon or a weapon system called Future Combat Systems, which is a very esoteric thing being developed for the Army. It’s a whole array of robots and sensors and of artillery pieces and other fancy weapons all linked together by computer. It’s all semiautomated. It’s a giant weapon in many, many different components. It will almost certainly never work properly. But the cost has now gone from 80 … it started off at around 60 billion and it’s now soared for a total lifetime cost of something on the order of $320 billion. Um, basically because he didn’t know or care that these sort of things aren’t going to work and you got to watch the military like hawks and not encourage them and not encourage this kind of push-button Star Wars warfare, which is what he did.

Harris: Is he doing this out of the evil of his heart? Is he doing these things because he really believes that the military should be stronger? What’s his purpose in doing all of these things?

Cockburn: Well … it’s always advertised that he was a deep thinker, and at least he had a penetrating intellect that liked to delve deeply into things. Maybe he does read a lot, I don’t know — he’s always telling us that he did. But the fact is that people who worked with him said that he was actually, they found him a rather superficial guy. That he wouldn’t, if he went to talk to them about a very complicated budget issue or technical issue to do with a weapon, he didn’t pay that much attention. He just said, “Oh, give me a summary.” So I think he’d absorbed some sort of fantasies that were being promoted by defense intellectuals around Washington, particularly the neoconservatives, and he just adopted that as his program. What he really liked doing was asserting his own political position. So this sort of thing was popular with the defense industry and popular with the [armed] services; I think he took it and ran with it. … Insofar as there was an agenda it was to dehumanize the whole defense system as much as possible.

Harris: And what do you mean by that?

Cockburn: Well, I mean someone compared it to the Death Star. Remember the old, the first “Star Wars” movie where they’re sitting in this sort of great artificial planet, the bad guys, and they have this weapon which can destroy an entire planet that you don’t even have to go near, you just push a button and it zaps it. Well, that was really the fantasy of Rumsfeld and his cronies, which was, instead of thinking about what, you know, what kind of war, what really the effect of a war is on our side and theirs and what happens if you just bomb people, how they react to that, bomb them from on high, or how, you know, what’s going to happen to our soldiers if you can’t be bothered to put proper armor on their vehicles, which he couldn’t. Instead of thinking about messy things like that they had this fantasy that you’d be able to sit in Washington, sit in the Pentagon, which is what they were doing, and you could look on your TV screen and see someone walking down a street in Afghanistan, on the other side of the world, and you could give a command and, zap, they’d be dead. And that’s what they liked and that was the kind of military that Rumsfeld was trying to build.

Harris: Perhaps his refusal to better outfit soldiers, to give them the vests and protection that they need, is justified by his wanting to say “I can take you out from right here, right now.” Has he always been working to set up that kind of facility?

Cockburn: Well, in a way … it’s where he’s coming from. You know that by adopting that program what you’re really doing is giving an awful lot of money to the defense contractors, which is really the name of the game. So, and it’s sort of a fan fictiony thing, it’s kind of attractive to anyone [who has] never been in a war, doesn’t know anything about war, doesn’t know anything about combat, doesn’t care. And it might be OK if they were just sort of spending money, you know just throwing money at their chums, I mean it was … reprehensible, but I mean it wouldn’t have been so bad for the world except that they went, then went off and launched a war to try it out. It’s the complete deliberate ignorance of reality, I guess. You know they went into Iraq just as they knew nothing about war, they knew nothing about Iraq. They just had this fantasy that, I mean which he presided over as the head of the nation’s military, that you could just march into Iraq and you could fight, march to Baghdad, roll to Baghdad and somehow magically the country would offer itself up once you’d taken away their bad fellow Saddam, the country would turn itself over to you.

Josh Scheer: Now, hi Andrew, this is Josh. Your book is not just … a modern history. It goes back to trace this man’s roots back further than just the Iraq war and just this president, and I was interested in the information you have and the press release I’ve gotten and it makes me want to read the book. The history of Rumsfeld with Ford and his relationship with Rockefeller and George H. W. Bush … was he allowed to do these kind of crazy things back then?

Cockburn: First thing you have to know about Donald Rumsfeld is he has always thought, or thought for a very long time, that there was no person in these United States better fitted to be president than himself. I mean he joined the Nixon White House and he was working his way up there. He got on quite well with Nixon, who called him the “ruthless little bastard,” which … was kind of [a] term of endearment for Nixon, I think. But then the … more important people to Nixon, like [Bob] Haldeman and [John] Ehrlichman, didn’t like him, didn’t trust him. So they exiled him to be the ambassador to NATO, which is where he was when Nixon fell, and then that was a big stroke of luck for him because then his old pal Gerry Ford, who he’d known when they were both in the Congress together, is president. And Ford brings him back to be chief of staff at the White House.

So then Rumsfeld, his eyes now are set on becoming president himself, and he decides the way he’ll do that is by first being vice president. So first of all there is a vice president — unfortunately, it’s Nelson Rockefeller — so he undermines him, which Rockefeller was always very bitter about. And then a rival for that position, for getting on the ticket in the next election, was George Bush Sr., Bush the father. So what he did with him was he was able to, you know he was very influential with Ford, and he got Ford to make Bush Sr. head of the CIA, which in those days, that was thought at the time that was like a political death knell for Bush and that he couldn’t come from that to run for elective office again. … That turned out not to be true, of course, but that’s what people thought. And Bush Sr. was very bitter about that and directly blamed Rumsfeld for what happened and never ever forgave him.

So, you know, there’s two things about Rumsfeld and they go together, which is, in those days, which is he’s very ambitious in a very sort of capable bureaucratic insider and backstabber, so that got him a long way. But at the same time precisely that behavior got him a lot of, earned him a lot of, very bitter enemies. And of course finally at the end of his career, last November, they brought him down.

Scheer: There’s a quote that you have that says, ” ‘No! This will never happen again.’ G.B.”

Cockburn: Well, that was George Bush, an example of George Bush’s lifelong loathing of — George Bush, Sr., I should say — loathing of Donald Rumsfeld. … There was a [1989] letter turned up at … the Bush transition office — Bush Sr. had just become president. And there was a letter that said, Dear Mr. President, I would like to apply — Dear Mr. President-Elect, Congratulations on your victory. I would like to be considered for the post of ambassadorship to Japan. Yours, Donald H. Rumsfeld. And scrolled across it, in big, angry letters, was ” ‘No! This will never happen!’ G.B.” So that’s, so Bush never forgave … they put out a lot of, you know there’s been some sort of misinformation that oh, that’s all in the past and Bush [Sr.] doesn’t care. But actually only last year Bush Sr. was actively lobbying to have Rumsfeld fired and was casting around for a replacement to recommend. So … George Bush Sr. still feels the same way about Don Rumsfeld as he always did.

Scheer: Now how did this, I mean, did he use this kind of conniving, backstabbing, bureaucrat way to get in with George H.W.’s son? I mean how did he get so much power?

Cockburn: Well, that’s interesting. He got … well, Rumsfeld, one among his assets, I mean to him, he has the capacity to size someone up and figure out their weakness, figure out their vulnerable points and play on that and intimidate them and keep them off balance. And he seems to be, seems to have done that with George Bush Jr. I mean I have any number of accounts from people who’d seen them together and been in those meetings at the White House where Rumsfeld would come in and there’d be a meeting in progress, Rumsfeld would be late and there’d be a meeting in progress where they’re deciding, well, they’ve decided what to do, you know Condoleezza Rice or someone had talked Bush into doing something, and then Rumsfeld would come in and say, “Uh, Mr. President, I think it’s the wrong way to do it, I think we should do this” … so Bush would like fall into line and reverse himself within minutes. I mean we have to understand, one of the reasons I wrote the book, I want to make it clear to people just how powerful this man has been. He wasn’t just Rummy the military component of the administration. Someone in the White House put it to me, he said — I asked, “Is he really that powerful?” And he said, “Are you kidding?” He said, “He controls half the discretionary spending of the United States government and he has a total veto on all U.S. foreign policy. How powerful is that?”

Harris: Due respect, this guy’s an appointed figure, and two times — he was the 13th secretary of defense, he was the 21st secretary of defense; do we exonerate Dick Cheney? Do we exonerate George Bush? They appointed this guy. And they have given him an open checkbook and they’ve given him all the power in the world to do what he wants. That’s at least my thought. I’d love to hear what you think.

Cockburn: Oh, yeah, that’s a very important point. Yeah, I don’t want to let any of the rest of them off the hook, both above and the ones you’ve just named. And also very importantly those sort of others below him. I mean, for example, Paul Wolfowitz was deputy secretary of defense and then in 2005 tiptoed away to be president of the World Bank, and if you’ll notice all the sort of rude things that have been written so far about the disaster of the Iraq invasion tend to let Mr. Wolfowitz off rather lightly, I guess because he’s been gone for a bit. But he was at least as culpable as Rumsfeld and the rest in sort of egging all this on. I mean Wolfowitz argued, he argued for sending, you know for doing it all with bombing like a lot of these neoconservatives — you know he’s mad for bombing people, very much in love in an ignorant kind of way with high technology, high-technology weapons. So yes, I mean the whole, I mean Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Richard Perle, another deeply guilty person who’s now trying to wriggle out of it by blaming everyone else. And of course George Bush and Dick Cheney. I mean the school of thought that says well the president was really in command, I really don’t … I mean that’s clearly not the case. He talked about answering to a higher father, not his real father; I think there were several higher fathers, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld.

Scheer: Do you know what Rumsfeld is doing right now? I mean is he gonna be the head of another organization like the World Bank?

Cockburn: What I think he’s doing right now, or he was doing until very recently was — most secretaries of defense when they leave office, they have a couple of people, they bring over a couple of aides just to sort of help sort through the papers and they get boxed up and sent off to the Hoover Institute or somewhere like that. Well, Rumsfeld had seven, seven full-time Pentagon employees, working full time in an office he was given, going through, I think they’re still at it, going through the record of his years of accomplishment as he sees it. I think he’s probably going to get, either write a book or get someone else to write a book, saying what a fantastic success it all was. I mean he, just before he left office he posted on the Pentagon website, there was a posting went up that said, “Rumsfeld, six years of accomplishment,” which included … developing new methods of interro — … new methods of getting information from prisoners at Guantanamo. Can you imagine? So he actually put torture up as an accomplishment.

Scheer: But he’s not influencing Robert Gates and others in the Pentagon?

Cockburn: No. You know that’s a very good question. If he is talking to them they’re keeping very, very quiet about it ’cause he’s so toxic. You know the whole point, Robert Gates got nominated and approved shamefully with the unanimous vote of the Congress — I mean which is very shameful considering who he is — because he was not Donald Rumsfeld. You know that was his prime recommendation for the job. So if [Gates] is talking to them … but you know even without him talking to them you know we’re living with [Rumsfeld’s] legacy. You know we have a military … I’d say the budget’s out of control. We got, you know we’re stuck with this awful war. We got, you know, troops badly protected, badly served with [their] weapons.

And I’ll give you an example which just struck me recently of his, of what a great manager he was…. He and Wolfowitz always liked to let it be known … they’d frequently go to Walter Reed just to check up on how the boys were doing and show how humane they were. You know, these kids they’d sent off to war, to get sent off to war to get blown to bits. Well, they’d go check up on them in the hospital. Well, recently The Washington Post did this excellent series pointing out the horrible Dickensian conditions at Walter Reed. You know with ceilings falling down, gaps in the ceiling, cockroaches and, worst of all, a completely uncaring bureaucracy. Well, you’d think some of these high and mighty characters with bleeding hearts, … making themselves feel better by going to Walter Reed, would have had a look around and done something for the poor souls who are up there.Scheer: You talked about torture early on in the interview and then we talked about Guantanamo Bay and he’s saying these are positives in his legacy. And a piece of new information that I got on this sheet and I read in your book was a quote that said, “Make sure this happens,” about Abu Ghraib. And I want to know if you wanted to comment on that a little bit, like, what was his involvement in that torture scandal and what did…?

Cockburn: Well … he did his best to, when it broke, he did his best to distance himself, to say how shocked he was, that it was the worst day of his life. He said he tried to resign and Bush wouldn’t take it. I mean this is a guy who could get Bush to reverse any decision, well, for most the time until they finally fired him. I mean one thing he was very good at was getting Bush to reverse the decisions that he, Rumsfeld, didn’t like. So if he really wanted to resign he could have. But, you know, he went on like that. But yet there’s abundant testimony that Rumsfeld was deeply involved in devising and in approving interrogation, i.e., torture techniques. That he was the guy who sent the commander of Guantanamo, Jeffrey Miller, sent him out to Abu Ghraib to Gitmo-lize it. … The quote you gave was on a bit of paper that someone found at Abu Ghraib [referring to] a list of torture techniques. So yeah, the whole response of the Defense Department was to blame it all on the National Guard military police unit from Cumberland County, Md., who indeed … behaved in a shocking way, but, you know, which deflects all the blame downwards. I mean I found one of the most extraordinary things was that they gave, during the prosecutions, they gave immunity to a colonel, a full colonel, so that he could testify against a dog handler, a sergeant, a specialist, I mean he wasn’t even a sergeant. So that’s not the way things are meant to work.

So, you know, the fact that Rumsfeld, although I’ve heard he’s now — you asked what he’s doing — I’ve heard he’s been seen at at least one big law firm in Washington presumably discussing possibly the defense he’s gonna need in the light of these lawsuits that are being brought both in this country and in Germany against him for being personally and directly responsible for the torture.

Harris: What do you think Donald Rumsfeld would say if he had a chance to respond to you about what you’ve written?

Cockburn: Oh, he’d probably say I was peddling al-Qaida disinformation. He’d change the subject. You know he’s very good at — I mean if he really chose to discuss it in detail, which he certainly wouldn’t, he would, he’d blame someone else. I mean there was a very telling moment I put at the end of the book where he, just a few days before he finally left the Pentagon, he went on a farewell tour to Iraq. And he went around various bases and he loved to have these town meetings where the soldiers who probably had better things to do but they would all be marched to sit in ranks in front and behind him so that, you know, [it would] make a nice picture, and he would lecture them, give of his wisdom for a bit and then invite questions … this is the secretary of defense and they’re just poor soldiers in the field…. But in Mosul, a base outside Mosul this last time, one soldier got up and said: Don’t you think you wish now you’d been, shown a little bit more patience? In looking for, you know, the inspections, looking for weapons of mass destruction before you invaded Iraq? You know, don’t you think you should have waited awhile? And Rumsfeld said, “Interesting. But you’re talking to the wrong guy. It was the president who made that decision, the Congress made that decision.”

In other words right up to the very end he can’t face up to the fact, in front of the guys he’s put in harm’s way, he can’t face up to the fact that he sent them. You know that it was his decision. Oh, no, it was the president. It was the Congress. It was Rumsfeld all over.

Harris: But isn’t that the privilege of the secretary position? That you don’t have to be accountable, that you can point your finger at the guys who are on top of you? I mean that’s his greatest luxury.

Cockburn: He obviously thought so. If you think that, you and he are about the only two people on this turning globe who think so. Everyone else thinks, hey, he was secretary of defense, he was Donald Rumsfeld. He was the most powerful man in an executive position in the U.S. government and if he, and if he’s too ashamed to admit his responsibility that really is a window into his soul.

Harris: Do you think anybody will ever take him to task for what he’s done?

Cockburn: Well, I have.

Harris: You have. I mean do you think he will suffer true legal consequence?

Cockburn: That’s an interesting question. I mean I don’t think he’ll be visiting Germany any time soon. Oh, he’d be advised not to. I think his travel, I think he is a bit worried. I was very interested to hear he’s been hanging out at, it was Williams and Connolly I heard he’s been seen at. Very big D.C. law firm. But he may have gone to others, for all I know. It’s interesting. … Unfortunately, his gang has taken over the judicial system to such a degree in this country that, you know, in this country unless things really, really change, I would say [there is] zero chance of him suffering judicial sanction here. But nonetheless … it’s worrying to have this legal process against him in Germany…. We have legal globalization to a degree now so that you can have assets seized. It’s a drag for him, and it’ll cause him to sort of [have], I don’t know, sleepless nights, but [at the least it will] cause him awkward, an awkward 15 minutes or so every so often.

Scheer: … We talk about Donald Rumsfeld being a neoconservative — he’s very toxic, as you said earlier. What about the other guys? I mean, are we going to see another rise of neocons? Are these guys, are they going to start all falling apart, or is this going to just continue every election cycle that we’re going to have neocons as just a new political party that we have to get used to?

Cockburn: Well, you know they’re in both parties and they sort of mutate. You know we have Democrat — … originally, you know, the neocons were all Democrats, like Wolfowitz. He was in a Democratic administration, he was in the Carter administration, it was his first biggish job. So they’re still around. …

The prominent ones are lying low, like this extraordinary outburst from Perle and Kenneth Adelman and a couple of the others about oh, it’s shocking, you know, the invasion of Iraq was a big mistake, it all turned out rottenly, you know, I had nothing to do with it … they did it so badly it’s all Rumsfeld’s fault. Well, I mean they were so deeply involved they were up and over their ears in it. First of all in promoting the whole idea to begin with. I mean a lot of decisions that went along with it. Their love affair with Ahmed Chalabi and so on and so forth. But, you know, so they’re discredited at least for the time being. Um, we have others. We have these fellows at The New Republic still working away and they still got their big think tanks. And the surge, you know the surge in Baghdad, that’s a neocon and it comes from Frederick Kagan … that legacy is still very much with us. I mean Cheney’s office is stuffed with neoconservatives. But it’s good that people point the finger at the neoconservatives and it’s good that they get blamed, but people shouldn’t let themselves off the hook either. There’s still an automatic, semiautomatic, tendency to believe them, you know, [as] the propaganda volume is turned up to full on Iran right now, you know, the menace of Iran. And speaking with a little bit of skepticism because of what happened in Iraq. But nonetheless I think if they do it right they could probably massage the media into endorsing some kind of strike against Iran. So, you know, yeah, the neoconservatives are still with us.

Harris: And I think they will be for some time. I hope you’re wrong about them [the media] being so flexible they could be pushed into a war into Iran, but time will tell, huh?

Cockburn: Yeah. I’m afraid so.

Harris: Andrew Cockburn has written the book “Rumsfeld: His Rise, Fall and Catastrophic Legacy.” If you have questions about what went on in 2002, what happened when we went in in 2003, I think Donald Rumsfeld is a good place to start. It’s a great book. You owe yourself the read. Andrew Cockburn, thank you for joining us on Truthdig.

Cockburn: I’m delighted. Thank you very much.

Harris: For Josh Scheer, for Andrew Cockburn, this is James Harris, and this is Truthdig.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.