An Improbable ‘Fraternity’

How did a pioneering group of students that included future Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas get into College of the Holy Cross, and how did they become leaders in American sports, culture, law and business? Author Diane Brady discusses what attracted her to their story.

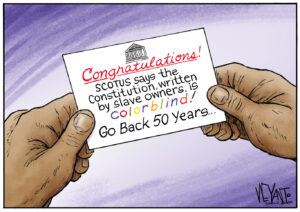

On Oct. 10, 2012, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case of Fisher v. Texas. At stake is whether to uphold a previous ruling (Grutter v. Bollinger, 2003), which would allow, in this case, the University of Texas at Austin to use race in undergraduate admissions decisions. Overruling the Grutter decision could eliminate the use of affirmative action in college admissions. The stakes are high, but the drama does not end there.

“The move to strike down racial preferences in college admissions brings together two of the most important men in American law: Clarence Thomas and Theodore V. Wells Jr.,” Diane Brady wrote in an article published in Bloomberg Businessweek at the time of the hearing. “The first is the most enigmatic member of the Court; the second is among the country’s top trial lawyers. One is expected to decide against the practice; the other helped craft the American Bar Association’s argument to maintain it.” A decision on the case is forthcoming.

Thomas and Wells are cut from the same collegial cloth. The two legal giants entered the College of the Holy Cross in 1968, a year that would prove a turning point for them, the school and a string of other successful students. If it hadn’t been for a decision that anticipated affirmative action, in which Thomas, Wells and a number of other black men were actively recruited to the school, their storied careers might never have occurred.

Father John Brooks, then head of the theology department at Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass., was deeply moved by the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He saw in King’s fall an opportunity to carry on the man’s legacy of compassion, equality and justice. The best way to do this, Brooks thought, was to integrate the mostly white campus, which then had only eight black students. At the dogged urging of Brooks, in 1968, Thomas, Wells and 18 other young black males were admitted.

Thomas, the second African-American to serve on the Supreme Court, and Wells, a prominent attorney whose clients include Eliot Spitzer, Scooter Libby, Citigroup and Exxon Mobil, went on to become hugely successful in the field of law. Three of their fellow classmates made equally impressive strides in other domains of society.

Eddie Jenkins is among them. Now also a successful lawyer, Jenkins played for the 1972 Miami Dolphins, the only NFL team to have a perfect season. Another star athlete-student, Stanley Grayson, served as one of New York City Mayor Ed Koch’s deputy mayors and is now president and chief operating officer of M.R. Beal & Company, one of the country’s oldest minority-owned investment banks. And the quiet Edward P. Jones, who teaches creative writing at George Washington University, not only won the 2004 Pulitzer Prize with his novel “The Known World,” he was awarded a coveted MacArthur genius grant the next year.

How did these men get to Holy Cross, and how did they evolve from a pioneering group of students into leaders in American sports, culture, law and business? This remarkable story is the subject of Diane Brady’s book “Fraternity.”

I met Brady at the headquarters of Bloomberg LP, parent company of Bloomberg Businessweek, where she serves as senior editor.

Shaun Randol: Is it fair to say this story found you, rather than you pursuing this story?

Diane Brady: Very much so. When I initially went to lunch with Stan Grayson, there was no agenda other than to meet this guy who is the head of the largest minority-owned investment bank. It was serendipity in the way that it happened to coincide with Ted Wells’ representation of Scooter Libby. Edward P. Jones also happened to be fairly top of mind, because not much time had passed since “The Known World” had come out. It was this confluence of events that made me think I’d like to find out more about these men and Father Brooks.

Randol: Why was Father Brooks so motivated to tell this story?

Brady: These are by their very nature, success stories. These are five men who succeeded remarkably. He, like a lot of people, is pretty disillusioned with what has happened in the decades since. In a way I think he saw it as a golden moment in his own life. He felt he had put a big emphasis on these guys as leaders, but he never got much attention for it.

Another reason is that I think he has sympathy for Clarence Thomas and feels that not only do people portray him unfairly in the media, but that Thomas was not always the way he is portrayed now.Randol: Of the 20 black men who entered Holy Cross in 1968, why did you focus on these five men? Six if you count Art Martin.

Brady: What I like about this story is that you have the marquee name of Clarence Thomas, who is a polarizing figure, and Ted Wells, who is clearly up there with David Boies as one of the top litigators of his generation. The fact that you also had literature [Jones] and Wall Street [Grayson] made it interesting to me, that it wasn’t this linear look at a bunch of guys who went into law.

Randol: What I like about the different stories is that there is one character that you can latch on to —

Brady: Who did you latch on to?

Randol: Edward P. Jones, but not because I had a similar college experience as him — I was a little more outgoing. In school I was probably more of an Art Martin. But now I feel an affinity with Mr. Jones, because I am a little quieter, a little more subdued, and I enjoy reading, writing and my time alone.

Brady: What’s interesting about him is that he’s also the least changed. When I’ve gone back and asked them questions like, “To what extent has the world changed or have you changed?” These guys, with the exception of Jones, have had lives of affluence and influence.

Jones really didn’t come into wealth, per se, until the last few years after the MacArthur grant. He’s also the most aware of continued racism and factors that made him angry in the ’60s; he doesn’t see the world as having changed that much. That makes him an interesting figure today. He has not joined the ruling class in any respect. He’s still very much on the outside.

Randol: Who did you most relate to?

Brady: A combination of Grayson and Wells, I suppose. Wells, for his workhorse nature. I was somebody who was a hard worker in school in part because I didn’t have this effervescent personality, like Jenkins has, and I don’t have any of the bitterness or anger or way of viewing the world that Thomas has.

One of the experiences that’s interesting about Wells and Grayson — and I did not have this — is there are certain people you know wake up in the morning and they look in the mirror and they know they’re winners. Even though Wells has been a hard worker, you can tell that all the way through life he’s always been a winner. He’s worked hard, but he’s never suffered the kind of complex that some of these other guys might have had. He’s never been made to feel inferior.

Partly why I am struggling with this is — I rarely see myself in the people I engage with. I’m very much the interviewer. I’m trying to figure out what makes them tick. It’s almost like a psychograph that you’re creating of what turns us all into the people that we become, and how does the impact of these moments in our lives change us? We all have those moments, and often the moment is related to school where there is a fork in the road and you’re given the impression that suddenly you’re good at something.

I was curious as to the fork in the road that these men met. Jones, for example, started out in math. The fact that he pivoted into writing was something that only really happened because of Holy Cross, he feels.

Wells I think would have done well anywhere he went, but Holy Cross probably gave him a heightened awareness of who he was. Thomas, I don’t know. He clearly had his eye on the Ivy League; I don’t know if he would have gotten there from where he was in Savannah, Ga.

Randol: I wonder if they all came to the same fork in the road, an intellectual one, in 1968 when Dr. King was assassinated. What I gather from “Fraternity” is that it seemed to be a moment when they were awakened to a larger world and political system. Even if they weren’t that engaged with Dr. King — they might have been more interested in Stokely Carmichael — that moment flipped a switch.

Brady: Certainly for Thomas it was the final straw for his time in the seminary, which was clearly ebbing in any case. Being a priest is not where he was ultimately going to end up. I think it cemented his bitterness. It was a big pivot in the road.

There is a before and after nature to Dr. King’s death, even more so I think than the whole death of Camelot mythology around Kennedy. Disillusionment set in with the death of King, so I think that did create more of an awareness.

Jenkins is very aware of it today; so is Wells. Thomas is aware of race in a very big way, but I think he’s quietly much more aware of the importance of lifting up, trying to do something about what’s happening to other young black men and women, that he doesn’t like to talk about in public. I think it is at the top of his mind for him, though. Randol: Were there questions that went unanswered? Or subjects that were off-limits?

Brady: There was a lot of reminiscing about Thomas where it was hard to tell whether people were projecting in light of their current views of him: sexism, jokes, that sort of thing. I have a little bit of that in there, but not as much because it felt like sometimes there was an agenda to the person telling the story.

At the same time, Thomas has a life script that he has to fit Holy Cross into, because Holy Cross diverges significantly from that life script. In his own memoir, very little space is dedicated to Holy Cross, something like four pages, and yet it was such an important period in his life. He loves Holy Cross, hated Yale, and yet to give it four pages while spending dozens and dozens of pages on his grandfather and chores — there’s a kind of mythology that you create when something doesn’t quite fit.

Randol: In what ways were the men unprepared for Holy Cross and vice versa?

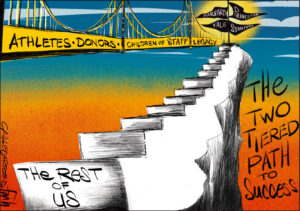

Brady: There was a mixed degree of preparedness. For somebody like Wells, for example, he had been a winner in an all black community, so he was a high achiever in sports and academics. To go from that to a somewhat isolated campus with different, Irish, Polish kids from the Boston area would have been a culture shock, regardless of skin color.

I don’t think they were prepared for how isolated they would feel. Both the isolation of Worcester and the isolation of just having so few people you knew at the time when consciousness about being black was high.

What way was the college not prepared? I think it’s very similar to the biases people have today with women or blacks or any other way we slice and dice ourselves — the assumption that if they were black that they weren’t deserving to be there. One thing Wells hated in particular was that if you were there on an athletic scholarship or perceived to be, people would automatically knock IQ points off because they would assume you wouldn’t get in academically. So he felt a need to prove himself against that.

I think the college also wasn’t prepared, frankly, for the assertiveness of this group. Once you had 20 of them, you’ve got the entitlement of youth, camaraderie, the power of the civil rights movement, and the sense that they’re visibly different and have different needs, and they were open about expressing those needs.

Randol: That sense of responsibility and obligation may be transferring to Latino college students, because now they’re getting into universities in sizable numbers. They’re starting to find a voice, and they’re feeling somewhat empowered by some of the things President Obama is doing in terms of immigration reform.

Brady: What’s different today, relatively speaking, is that the societal responsibility that we have to each other — to have equal opportunities — is not there in the same degree that it was there in the late ’60s.

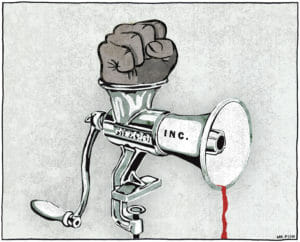

Now, again, you had MLK. There was a moment in time. I’m not saying it continued, necessarily, but one thing that is interesting with Ted Wells is that he feels that all the talk about diversity does, in a way, denude the unique nature of the black experience in this country, with slavery and the way African-Americans are viewed. He feels something has been lost in the conversation by having it become everything from somebody who has just arrived from China and they’ve got a million dollars in their pocket, versus somebody whose ancestors were brought over as slaves, and the mindset that creates. It’s not all the same and it all can’t fall under the same category of “you’re not a white man, ergo you’re a part of diversity.” He feels a bit of wistfulness that something is being lost.

Randol: There’s not a singular minority experience.

Brady: And there’s not a push to right a wrong.

Randol: In the black community as well, do you think?

Brady: I think the black community now talks about the battle being financial. There was a time when entrepreneurship was big in the black community because you couldn’t get served [because of segregation]. You had an entire ecosystem of black businesses serving black consumers the same way you do now for Latinos. That ecosystem doesn’t exist so much today, probably for a lot of reasons, access to capital, who knows what? African-Americans have one of the lowest rates of starting businesses; they have real disappointment not so much with African-American women but certainly with black men, that they’re not succeeding in college. I think there’s a bit of angst over how to address these problems because they’re happening on so many different levels. At the same time, some of the tools that the men had at Holy Cross, a sense that there is a moral responsibility to letting black students have this opportunity, that’s diminished somewhat.

What’s interesting about Wells is that he went on to Harvard and went to school with Ken Frazier, who’s the CEO of Merck, and Ken Chenault, who’s the CEO of American Express, so his classmates from Harvard are equally impressive. But Holy Cross is the one that has that special place for him. You can’t say it’s all wistful because there’s been huge success. We’re sitting here with a black president. There’s the obvious success.

There is an awareness that just to let things go on as they’re going, to not bring race back into the conversation comes at the expense of the black community to some extent. Maybe race is too much of a conversation to a point where we’re all numb to it, I don’t know. We frame it now as economic opportunity, which I guess is somewhat right.

I think what bothers Thomas so much about the affirmative action conversation is the fact that these kids are being pulled into places where they are being set up to fail. That all the attention is getting them into college when in fact they don’t qualify to be at Harvard and they would do better to be at a Georgia college. There’s no acknowledgment that, in many cases, students are coming out of a school system that has not left them equipped to be in an Ivy League college. He’s aware of that and feels that Holy Cross was a perfect school for him because it was hard, but it was just right for his skills. He says that if he had been coming out of high school today, that he might have been propelled into a program where he couldn’t cope because he wouldn’t be coming in with the same level of academic background. He had some help, the right type of help, and it wasn’t anything to be ashamed of. He had the opportunity and he made the most of it.

Randol: What should the general reader take away from “Fraternity”?

Brady: Ultimately, it’s about a moment in time and to some extent, even though it wasn’t intended to be this, I do think it’s partly a testament to the power of affirmative action and what it can do for people. There’s no question that Ed Jones technically didn’t qualify to be at Holy Cross, but here we are today — he’s a MacArthur genius who’s added to an element of literature we wouldn’t have had if he didn’t put pen to paper.

“Fraternity” says something about leadership coming in many forms and how we have such a limited route through which we bring people up. The kids who had the opportunity to go to school with these 20 guys were better off than the years before, in the same way that the group that followed who had the opportunity to go to school with women were better off. People are better off when you mix it up.

Shaun Randol is the founder and editor of The Mantle. He is also an Associate Fellow at the World Policy Institute in New York City, and a member of the National Book Critics Circle and the PEN American Center. You can follow him on Twitter @shaunrandol.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.