American Vivisection

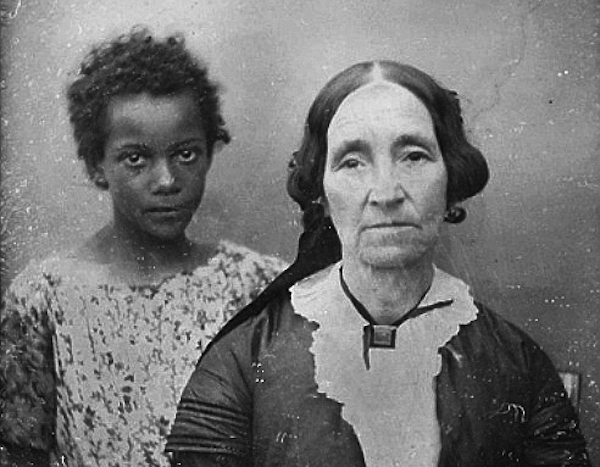

A new book uses multiple instruments to dissect the illiberal American mind, returning always to Ground Zero: racism. A woman from New Orleans, Louisiana and an enslaved servant girl, mid-19th century. (Wikimedia Commons)

A woman from New Orleans, Louisiana and an enslaved servant girl, mid-19th century. (Wikimedia Commons)

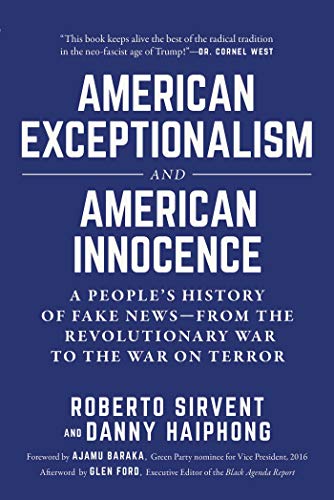

A book by Roberto Sirvent and Danny Haiphong

When I lived in Argentina 15 years ago, I would often practice my Spanish—and in all candor amuse myself—by asking cabbies, barbers and bartenders a question: “How did Argentines create their world-famous dance, the Tango?” If I asked a dozen people this question, I heard some derivation of this response no less than 11 times:

“We stole it from the blacks.”

As a black man who grew up in the Midwest, this blunt, unhesitating admission of cultural appropriation struck me as extraordinary. In my experience, if you asked a dozen random whites in the U.S. what musical genre most influenced Elvis, Willie Nelson or the Beatles, you’d best not hold your breath, as the saying goes, waiting to hear anyone pay homage to a blues tradition exported from West Africa.

The cause of these differing responses from the descendants of European settlers in Buenos Aires and, say, Boston, are the twin scourges of “American Exceptionalism and American Innocence”—the title of a startling new book by Roberto Sirvent and Danny Haiphong. At once redolent of classic works by Howard Zinn and Frantz Fanon, as well as “Freakonomics” by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven Levitt, an offbeat take on behavioral economics, Sirvent and Haiphong expertly dissect the illogic of the illiberal American mind and the violence it has wrought, both at home and abroad.

As one might expect, this is the quintessential heavy lift, yet the authors execute their task with a deft touch, producing 21 seemingly effortless essays that blend robust reportage, political science, economics, cultural criticism and storytelling, that, if not quite poetry, is entertaining, fluid and accessible. But while it is an easy and engaging read, the book is nonetheless a provocation. Consider their take on “fake news” in the introduction:

What is ironic is that fake news has indeed been the only news disseminated by the rulers of the U.S. empire. We’ve been exposed to this fake news for as long as we’ve been told that the U.S. is a force for good in the world—news that slavery is a thing of the past, that we don’t really live on stolen land, that wars are fought to spread freedom and democracy, that a rising tide lifts all boats, that prisons keep us safe, and that the police serve and protect. Thus, the only “news” ever reported by various channels of the U.S. empire is the news of American exceptionalism and American innocence. And as this book will hopefully show, it’s all fake.

Click here to read long excerpts from “American Exceptionalism” at Google Books.

Challenging the white savior complex, the authors quote Ifi Amadiume, an African feminist writer, describing her encounter with a well-meaning university student:

I asked a young White woman why she was studying social anthropology. She replied that she was hoping to go to Zimbabwe, and felt that she could help women thereby advising them how to organize. The Black women in the audience gasped in astonishment. Here was someone scarcely past girlhood, who had just started university and had never fought a war in her life. She was planning to go to Africa to teach female veterans of a liberation struggle how to organize! This is the kind of arrogant, if not absurd attitude we encounter repeatedly. It makes one think: Better the distant armchair anthropologists than these ‘sisters.’

Sirvent, a professor of political and social ethics at Hope International University, and Haiphong, a columnist for the radical Black Agenda Report, make no pretense of cable news-like objectivity: They have skin in the game, and flatly say so. Their goal in writing this book is to conscientize a new generation of activists, and renew an anti-imperialist and antiwar movement that began to lose its way nearly half a century ago. It is this almost evangelical zeal, their willingness to testify and bear witness, and their irreverence for the church of American exceptionalism that rescues the book from the detached, academic tone that so often relegates books of this nature to the groaning, dusty shelves of a university library.

If their book is indeed a dissection (or perhaps vivisection is more accurate), then Sirvent and Haiphong use multiple instruments to conduct their examination, invoking everything from Captain America’s shield to the Broadway play “Hamilton,” from 9/11 to the NFL draft, immigration to the invasion of Afghanistan. But they always seem to return to Ground Zero, which is racism, generally, and anti-black racism, specifically.

American exceptionalism and innocence are inherently white supremacist ideologies. The former presumes that American national superiority should be appreciated by racially oppressed people regardless of their circumstances, and the latter assumes that past racist crimes have been rectified by the benevolence of institutions dominated by white America.

This is an exhaustive book; that represents perhaps the only viable criticism. Would the book benefit from being shorn of 40 pages? Maybe. It might have sped up an already fast read, and sharpened the narrative a bit. But the authors’ encyclopedic approach is part of its triumph as well. So overwhelmed is the reader by book’s end that one gets the feeling of having witnessed a long and brutal Guantanamo-like interrogation of the American body politic, its hands and feet manacled to an unadorned chair in a shadowy room, with Sirvent and Haiphong peppering the suspected terrorist with a series of leading and uncomfortable questions.

“American Exceptionalism” is a remarkable work of both scholarship and writing. In unfussy but searing language it identifies the cultural gene that distinguishes the white settler in the U.S. from kith and kin elsewhere in the New World. Anyone who has ever visited Argentina knows that Argentines are not without their biases—as Eva Peron, Adolf Eichmann and River versus Boca demonstrate—but perhaps because practically everyone who lives there today is white, they never felt the need to institutionalize their bigotry as a means of dividing the working class. Whatever the reason, it is tempting to reduce “American Exceptionalism’s” 360 pages to a single sentence plumbed from a book authored by Eichmann’s boss, Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf”:

The great masses of the people… will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one. Jon Jeter is a former Washington Post bureau chief for southern Africa and South America, a producer for the popular documentary radio program “This American Life,” and the author of “Flat Broke in the Free Market: How Globalization Fleeced Working People,” and the co-author of “A Day Late and a Dollar Short: High Hopes and Deferred Dreams in Obama’s Post Racial America.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.