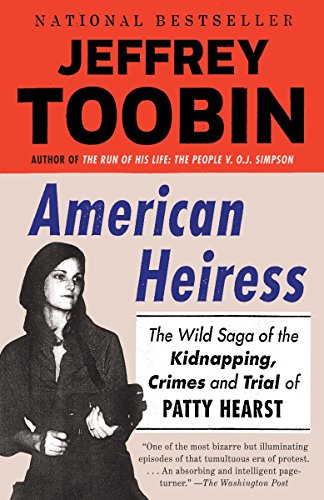

American Heiress

Patty Hearst's wild saga "provided hints of what America would become," in the words of author Jeffrey Toobin -- a sensational true crime story and a sad comment on American justice, race relations, media and celebrity culture.Patty Hearst's wild saga "provided hints of what America would become," in the words of author Jeffrey Toobin—a sensational true crime story and a sad comment on American justice, race relations, media and celebrity culture.

“American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst” A book by Jeffrey Toobin

Patty Hearst’s story seems an unlikely topic for Jeffrey Toobin, the former prosecutor and staff writer at The New Yorker. His books typically arise from firsthand reporting of high-profile cases, most notably the trial of O.J. Simpson. Toobin’s new book, “American Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst,” however, is set amid the revolutionary violence of the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-1970s, when Toobin was a teenager in New York City. San Francisco had already endured the Zodiac and Zebra killings, and more mayhem was yet to come. Yet Patty Hearst’s wild saga is one of the strangest episodes in what author David Talbot calls San Francisco’s “season of the witch.”

Toobin tells his story methodically, beginning with Hearst’s abduction from her student apartment in Berkeley. By that time, the ragtag Symbionese Liberation Army had already assassinated Marcus Foster, the black school superintendent in Oakland. After other leftist groups condemned that senseless act, the SLA changed its tactics. It hoped to exchange Patty Hearst — whose wealthy grandfather, media titan William Randolph Hearst, perfected “yellow journalism” — for the two comrades arrested for Foster’s murder. When that gambit failed, the SLA demanded that the Hearst family fund a massive distribution of food in poor Bay Area neighborhoods. Meanwhile, Patty Hearst spent 57 days in a closet. To everyone’s shock, she then announced she had joined the SLA. Many wondered about her announcement’s authenticity, but Hearst participated in two SLA bank robberies, the second of which left one customer dead.

Hearst and her comrades went underground, eventually holing up in Los Angeles. Shortly after the FBI located their Compton hideout, half the SLA members perished in a shootout during which their house was incinerated. Hearst and the other survivors went underground for 15 months before the FBI captured them in San Francisco. When booked, Hearst raised her handcuffed fist defiantly and described her occupation as “urban guerrilla.” Her attorneys, however, claimed that her SLA comrades had raped and brainwashed her. Convicted for her part in the first bank robbery, Hearst received immunity in the capital case after agreeing to testify against her comrades. She served 22 months of her seven-year sentence before President Carter commuted it. After her release, she married the head of her private security detail, moved to Connecticut, wrote a best-selling memoir, and eventually received a full pardon from President Clinton.

Even those who remember this mid-century madness will appreciate Toobin’s account, which draws on interviews, FBI reports, and unpublished source material Toobin purchased from Bill Harris, one of Hearst’s kidnappers, after his release from prison in 2008. Toobin’s narrative is clear and cogent, but he is strongest when dissecting the trial’s procedures, legal strategies, gaffes and verdict. He explains, for example, why jurors doubted Hearst’s claim that her comrades raped her. Acting on a late tip from the only female member of the prosecution, the district attorney proved that Hearst had worn and retained a necklace given to her by her purported rapist, who died in the Los Angeles firefight. Toobin also shows why jurors determined that Hearst could have escaped her captors at least once during her time in Los Angeles. Instead of doing so, she helped extricate Bill Harris from a scuffle outside a sporting goods store. (Harris shoplifted a bandolier, and Hearst sprayed machine gun fire to discourage the security guard.) In the end, the judge’s instructions militated against the brainwashing argument that superstar attorney F. Lee Bailey had fashioned for the defense.

Much like Brian Burrough’s “Days of Rage,” which cataloged the many acts of revolutionary violence during this period, “American Heiress” is occasionally light on social and political context. For example, Toobin notes that the FBI’s reputation plummeted during the mid-1970s, especially after the public first learned that the bureau had routinely surveilled, infiltrated and harassed law-abiding leftist groups. When combined with the slaughter in Vietnam, Watergate scandal and fresh evidence of illicit CIA operations, that disclosure further eroded the public’s faith in government institutions. But Toobin’s brisk narrative never quite connects the systemic abuse of state power to the perceived need for militant action; as a result, the revolutionary violence of that period seems even crazier than it was.

Toobin is better on the prison movement, which shaped SLA leader Donald DeFreeze’s peculiar ideology. Also known as General Field Marshal Cinque, DeFreeze was a product of the prison system and the violent black nationalism it spawned. Most SLA members were white Berkeley residents who, after tutoring in a nearby state penitentiary, were radicalized by the prison movement. Toobin notes that prison guerrilla George Jackson’s original sentence — one year to life — was common at that time but now seems absurd.

A legal analyst for CNN, Toobin is attuned to the media frenzy that surrounded Hearst’s lethal adventure, especially the coverage of the Los Angeles shootout. The KNXT news team, which had exclusive access to Minicam technology, filmed the shootout from close range. Within minutes, KNXT shared its live signal with other stations. It was the first unplanned breaking news event broadcast live across the nation. Curiously, Toobin ignores Rolling Stone’s first major investigative story about Hearst’s underground experience. The anonymous source for that two-part piece, which appeared a month after her arrest, was sports activist Jack Scott, who wished to write about the SLA, arranged secret meetings with its members, and drove Hearst cross-country as she fled law enforcement. Scott, whose friendship with NBA star Bill Walton also kept him in the media spotlight, later received $30,000 to settle a libel lawsuit prompted by Hearst’s memoir.

Toobin concludes that Patty Hearst was first and foremost a rational actor. “Even in chaotic surroundings,” he claims, “she always knew where her best interests lay.” Her decision to join the SLA was as shrewd as her decision to abandon her comrades after her capture. Toobin also focuses on the ordeal of Randy and Catherine Hearst, Patty’s parents, as they struggled with the kidnapping, negotiations, media frenzy, trial and pardon. Though flawed, they are portrayed sympathetically. Not so with Steven Weed, Hearst’s fiancé, who managed to escape their Berkeley apartment during the abduction and then to alienate Patty, her parents and the American public.

Finally, Toobin features the characters who populated the edges of Hearst’s story. Robert Shapiro, who would later work with Bailey on the O.J. Simpson case, makes a cameo appearance. Lance Ito, the judge in that case, briefly shared a shooting range with a machine-gun toting SLA member. Reverend Jim Jones offered to help with the food distribution effort; that enterprise also employed Sara Jane Moore, who served 32 years for attempting to assassinate President Gerald Ford during his 1975 visit to San Francisco. Congressman Leo Ryan, who represented Randy and Catherine Hearst’s district, endorsed the commutation of Patty’s sentence. “Off to Guyana,” he wrote Patty in 1978. “See you when I return. Hang in there.” Jim Jones’ henchmen shot and killed Ryan before he could board his flight home. Robert Mueller, the U.S. Attorney in San Francisco before taking over as FBI director, strenuously opposed Hearst’s pardon, claiming that her attitude, born of wealth and social position, “has always been that she is a person above the law.” Even Truthdig editor Robert Scheer makes an appearance; he interviewed Bill and Emily Harris in jail for a New Times piece that appeared toward the end of the trial.

Toobin correctly maintains that the Patty Hearst affair “provided hints of what America would become.” More specifically, “American Heiress” reads like a prequel to the O.J. Simpson affair. Both were sensational true crime stories as well as sad comments on American justice, race relations, media, and celebrity culture. One wonders whether William Randolph Hearst could have detected his own contribution to that America.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.