All the Wild That Remains

Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner are two of the most influential Western environmentalists and writers of the 20th century. A new book, "All the Wild That Remains," is an excellent primer for readers new to Abbey and Stegner and their continuing relevance. W. W. Norton & Company

W. W. Norton & Company

W. W. Norton & Company

“All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West” A book by David Gessner

If you mention Wallace Stegner or Edward Abbey to a reader in the Western United States — Utah, say, or Montana — you’re likely to hear a strong opinion, and possibly even a personal anecdote, about “Wally” or “Ed,” two of the most influential Western novelists and environmentalists of the 20th century. But when David Gessner told friends in the East he was writing a book about them, “their names, as often as not, elicited puzzlement.” Did he mean Wallace Stevens? Edward Albee? This, even though “Stegner and Abbey were both so firmly entrenched in the pantheon of writers of the American West that if the region had a literary Mount Rushmore their faces would be chiseled on it.”

Gessner’s book serves as an excellent primer to readers new to Abbey and Stegner and an insightful explanation of their continuing relevance. Gessner, an important nature writer and editor in his own right, also uses the writers’ lives as a template for his own exploration of the Western landscape they lived in and wrote about. He visits places that were important to Abbey and Stegner, and draws trenchant conclusions about the current state of affairs in a region still battling over how to best protect and exploit its fragile resources.

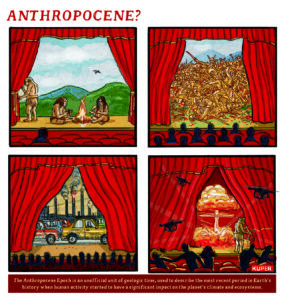

Stegner and Abbey are a study in contrasts. Abbey was a self-styled wild man — “his persona was lecherous, combative, unpredictable, contradictory.” His most lasting work is “Desert Solitaire,” a hilarious and moving nonfiction account of two years he spent as a park ranger in Utah that, Gessner writes, “some consider the closest thing to a modern Walden.” His novel “The Monkey-Wrench Gang,” about a group of vigilante environmentalists who dismantle construction equipment and plot to blow up the Glen Canyon dam influenced a generation of radical environmentalists, or eco-terrorists, depending on one’s perspective.

Stegner was significantly more tempered in his conduct, and his portion of the book is sometimes overshadowed by Abbey’s. Stegner had a peripatetic childhood, shaped by a father who roamed the West looking to strike it rich. Perhaps as a result, Stegner prized order above all in his mature life, founding and then spending decades teaching in Stanford’s creative writing program (where Abbey was, briefly, one of his students) and working to affect national environmental policy through focused, dogged advocacy. His major achievements as a fiction writer — the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Angle of Repose” and the autobiographical “Crossing to Safety” — came late in his long life.

Gessner’s reporting, whether profiling Stegner and Abbey’s acolyte Wendell Berry or observing the consequences of Vernal, Utah’s fracking boom, is vivid and personable. In his able hands, Abbey and Stegner’s legacy is refreshed for a new generation of readers. Perhaps now even the Easterners will take notice.

Andrew Martin is a fiction writer and teacher whose work has appeared in the Paris Review, the New York Review of Books and many other publications.

©2015, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.