After 2016’s Losses, Elizabeth Warren Tells Democrats: ‘Shame On Us’

The story the Massachusetts senator tells about the election and America's anxieties is curiously one-dimensional.

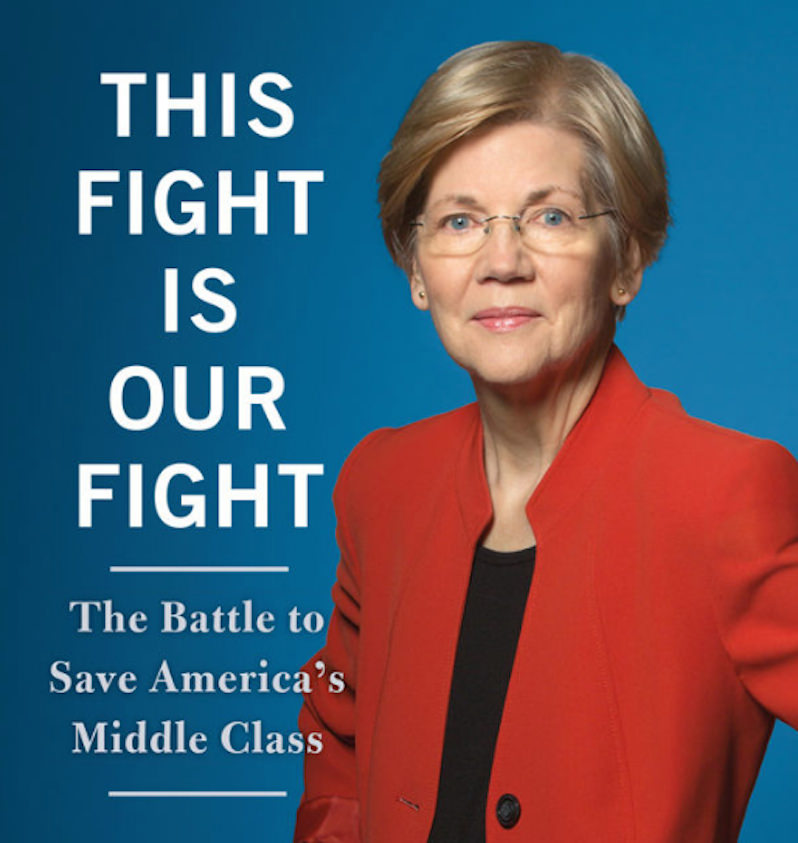

Metropolitan Books

“This Fight Is Our Fight: The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class”

A book by Elizabeth Warren

During a moment alone with Hillary Clinton before an October campaign event in New Hampshire, Elizabeth Warren recalls, the presidential nominee seemed confident: She “smiled and said the numbers looked good.”

But Warren didn’t share the candidate’s optimism. “I was anxious, right down to my bones,” she writes with the faux folksiness that winds through her new book, “This Fight Is Our Fight.” The senator from Massachusetts saw Donald Trump as an extreme version of Ronald Reagan – his vision was “like the conservative philosophy on steroids.” She was trying to “sound the alarm” but worried she wasn’t doing so “loudly enough.”

This Fight Is Our Fight: The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

This Fight Is Our Fight: The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

And now she is angry about the consequences. She writes that regulatory rollbacks make her “mad, spitting mad.” The “sick-in-the-back-of-the-throat unfairness” of legislators opposing the minimum wage “nearly chokes me,” she says, and the revolving door between Goldman Sachs and federal office “makes me gag.” Warren repeats her list of enemies like a talisman: corporate executives, greedy bankers, perma-pundits who take private-sector kickbacks. And her arch-nemesis is clear: “During my time in office I’ve learned a bitter lesson,” she writes. “A Republican-led Congress just doesn’t care.”

Since she got to Washington, Warren has embraced a moral language Democrats often struggle with: good old-fashioned economic populism, complete with references to “good guys” and bad guys and loads of fiery outrage. Increasingly, populist anger may be the favored language of liberals. With Sen. Bernie Sanders’ surprise success and Clinton’s shocking failure in 2016, lefty progressives have spent the past few months saying, “I told you so.” “This Fight Is Our Fight” is no exception.

But Warren’s book also reveals the moral languages the senator is less able to speak. She never truly grapples with why Democrats lost, why middle-class voters would choose Trump or whether their anger might be about more than the economy. Warren sees the world through the narrow lens of economic interests, ignoring the deeply held values and beliefs that often determine people’s politics. This attitude is condescending, but more important, it limits Warren’s understanding of America – and why her party has failed so badly.

Warren has a playbook for Democrats: Talk about the middle class, not the poor. Focus on regulation and corruption, not taxing and spending. And at every possible moment, highlight the hypocrisy and corruption of the other side. She details policy proposals in bulleted lists and anecdotes, mixing stories from her Oklahoma childhood with narratives about middle-class Americans who worked hard and still ended up struggling with money.

“This Fight Is Our Fight” could conveniently double as a slogan for a national campaign, one very different from Clinton’s “Stronger Together.” In her retelling of the elections that left Republicans in control of the White House, Congress, 32 statehouses and 33 governor’s mansions, Warren styles herself as a populist Cassandra who expected Trump’s victory. Clinton earns no praise for her policies or leadership – Warren subtly suggests that her endorsement was more practical than ideological. But she makes sure to include a nod to her fellow senator from New England: “Bernie was amazing. Passionate. Smart. Totally committed,” Warren writes. “I was reminded why we had been friends for so many years.”

Sanders-style progressivism is where the party should go, she argues – away from the free-trade liberalism championed by Democrats like Bill Clinton, whom Warren criticizes for pushing forward “tax cuts and deregulation” with the repeal of the Glass-Steagall financial regulations. After years of “a booming stock market and a rich payoff for those with big investment portfolios and fancy corporate jobs,” she argues, “it’s time to raise this question: Is this the best that capitalism has to offer?”

Warren has nominated herself as the person to answer that question – perhaps as a senator, perhaps as president. She declined to run for the White House in 2016, despite rumors that she might. (To the anonymous sources who claimed to “know her thinking” in the press, Warren says: “Um, seriously?”) Now she seems to be offering her own soft pitch: Unlike other Democrats, she understands the anger of the American people, she predicted Trump’s success, and she knows what the party should do next.

Yet the story Warren tells about the election and America’s anxieties is curiously one-dimensional. She uses standard progressive math to explain Trump voters: Some are racist bigots, some were taken in by a huckster casino owner, and some are suffering from intense economic despair. One of the women she follows, Gina, lives in a mobile home in a small North Carolina town. She and her husband barely get by on her hourly wage from Walmart. “We need to tell this story!” Gina tells Warren. “But I really need this job.”

Gina, we find out at the end of the book, “proudly voted for Donald Trump, hoping he would ‘shake things up.'” In Warren’s world, the Democratic Party would win the vote of every Gina in America by fighting for a “playing field that isn’t tilted so hard against her.” But Warren never really tells us why America’s Ginas aren’t voting for Democrats now.

Perhaps Warren’s narrow lens has something to do with it. While she mentions the problems of racism and tosses in an obligatory shout-out to Planned Parenthood, those issues are not central to her narrative of how America got the way it is and how Democrats need to fix it. She gives no credence to people’s religious convictions and moral crises. She spends no time on battles over LGBT identity or racialized policing. And she has no patience for arguments in favor of smaller government. To Warren, real political action is never local and communal, but always federal.

Some 200 pages in, it comes: a brief flicker of culpability, a feint at explanation. “Obviously, not enough voters had believed that Clinton was the candidate most committed to fighting for their families,” Warren writes. “Our side hadn’t closed the deal. … Shame on us.”

It’s an admission of tactical failure, nothing more. That little word, “us,” is Warren’s only nod to the possibility that she might bear some responsibility for her party’s failures and the dismal state of American politics generally. Democrats’ shame is there. But Warren isn’t about to share it.

Emma Green is a staff writer at the Atlantic, where she covers politics, policy and religion.

©2017, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.