Abbie Hoffman Was Here

Hoffman famously said, “You measure democracy by the freedom it gives its dissidents, not the freedom it gives its assimilated conformists.” This was in 1989, when he was just 52, the same year that he killed himself, making everyone wonder if freedom wasn’t really just another word for nothing left to lose. Hoffman famously said, “You measure democracy by the freedom it gives its dissidents, not the freedom it gives its assimilated conformists.”

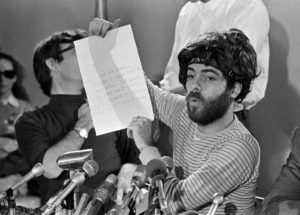

Abbie Hoffman, the wild-haired personification of both the noun and adjective form of the word “riot” in the 1960s, nostalgically revered by the current liberal Democratic wing of the Establishment Party as the Tourette’s of the Anti-Establishmentarian Movement and the joy-buzzing co-confounder of the Yippies, his significance neutered by his infamy, his legacy no more useful to contemporary radical politics than the miniskirt or the lava lamp, famously said, “You measure democracy by the freedom it gives its dissidents, not the freedom it gives its assimilated conformists.” This was in 1989, when Hoffman was just 52, the same year that he killed himself, making everyone wonder if freedom wasn’t really just another word for nothing left to lose. His body was found in a converted turkey coop near New Hope, Pa., where I found myself a week ago, seated behind a small lopsided table on the sidewalk outside of Farley’s Bookshop, trying to sell my new book of cartoons and essays about how we’re all doomed to tourists and retirees in white linen shorts, crisp running shoes and “God Bless America!” T-shirts.

Roasting beneath the spectacular rage of the mid-July sun while the delicious scent of Abbie Hoffman’s martyred ghost swirled around my starvation for attention like a home-cooked meal, I started to imagine that if only my book loaded with chocolate chips and cut into bite-sized pieces and I were wearing an apron I might gain some acknowledgement from the public.

A week earlier I was at the Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn, drinking red wine from a plastic tumbler and standing before a microphone while the immense rain-soaked windows behind me fogged and perspired, the body heat and carbon dioxide from the overflow crowd overpowering the air conditioning like Bolshevism. The event had been organized by my publisher, Akashic Books, and featured short readings and presentations by a handful of the house’s writers and felt not unlike what I imagined poetry readings at the Six Gallery in San Francisco must’ve been like in the 1950s, more like an Irish wake for the written word than a subdued Lutheran funeral. Following closely behind a short presentation by Adam Mansbach, author of “Go the F**k to Sleep,” this year’s “Chicken Soup for the Soul,” I couldn’t resist saying to the audience, in mock disgust, “Before I begin, let me just say that I’ve spent my entire artistic career saying ‘fuck’ to the most despicable politicians and the most ruthless warmongering men and women of industry and high finance, never realizing that if only I’d said it to sleepless children I’d be on the New York Times bestseller list and not counting nickels to buy my toilet paper.” It was a party.

I remember back when I first saw Dick Lester’s deeply significant 1964 film masterpiece, “A Hard Day’s Night,” and how the scene at the discothèque changed my life forever. It was the part of the movie where we find our lovable heroes, the Beatles, tired of being quarantined in their hotel room between public appearances and they decide to sneak out and go to a club to dance and meet girls. Most remarkable to me, and I was probably 12 at the time, was how cool John Lennon looked by not dancing as the other three were, choosing instead to sit and drink and talk — to philosophize, I guessed, judging by the attentiveness of his listeners and the soigné manner in which he held his cigarette! — with those around him. It seemed antithetical to all that I had been led to believe by the dominant culture about what grooviness and hipness were supposed to look like. What was hipness, particularly for a boy, supposed to look like? Well, the way I understood it was that hipness was largely determined by how well a fella could throw and catch a ball, how handy he was with tools and how gracefully he was able to communicate nonverbally with the opposite sex, whether through dancing, kissing or snubbing. Yet here was Lennon, in a black turtleneck and surrounded by beautiful women, appearing absolutely at home in his own skin, no ball or hammer or ChapStick anywhere in sight, just straight confabulation, pure and simple. The idea that one could appear gorgeous merely by having a conversation was somehow wonderful to me, and I decided to make it my life’s ambition to define my own grooviness by engaging in a never-ending dialogue with as many people as I could. What would be the point, I suddenly realized, of wasting my time trying to emulate the wordless and episodic pantomime that I saw everybody else engaging in with one person at a time?

“Did you make this book yourself?” asked a sapid old lady in half glasses and a pair of powder blue Bermuda shorts approximating the size of the landmass they were named after. She was standing at my sidewalk table, having come from nowhere, caressing the cover of my book like she was hoping to provoke a purr, a needle-thin crucifix hanging from her neck on a chain the width of a thread.

“Yes,” I said, smiling up at her in my Buddy Holly glasses, fresh haircut and three-button blazer, the perfect picture of benign Christianity and cherry-cheeked Americanism. Then she opened the book and concentrated on a random page, mumbling silently to herself the gagline to one of my cartoons. In an instant the sweetness drained from her face and she closed the book and slowly returned it back to its stack, her eyes tearing as if she’d just halved a red onion the size of John the Baptist’s felled head. “Well?” I asked her.

“You should be ashamed of yourself,” she spat, turning away and marching off in the direction of a live klezmer band playing the theme to “Rocky.” What struck me as peculiar was how this woman, who no doubt had lived through the Great Depression, who had seen the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the My Lai Massacre and 9/11, who had witnessed the mind-numbing tragedy of the Holocaust and experienced the devastation of environmental decay and worldwide unrest and famine and public assassination, could react to something I’d drawn as if a new benchmark for unspeakable horror had been set.

“What is ‘Go Fish: How to Win Contempt and Influence People’ about?” I’d said at the Greenlight, referring to the book that I held in my hand, just as the light changed at a nearby intersection and a serpentine line of Brooklyn traffic slowly panned its headlights across my back and sent an elegant succession of shadows pirouetting around the bookstore like joyous slaves. “Let me answer that question by telling you about a young man who wanted nothing more in his life than to be a famous artist,” I said. “He hated school, used to get in trouble for daydreaming all the time. He would lose entire afternoons meditating on the beauty of objects, on the aesthetics of light and shadow, his fingers forever smudged with oil paint, his clothes smelling of turpentine, his heart and mind awash in hope and optimism.” I paused, afraid of choking up.

“For him,” I continued, “there was no higher calling than to be a painter who created beautiful images for the public and who lived his life in service of his craft, his canvases designed for the singular purpose of inspiring people’s souls to grow. That young artist’s name …” — I stopped, looked around the room, then back at the book in my hand — “… was Adolf Hitler. The moral of the story being that if only we lived in a world less inclined to discourage lousy artists from continuing to create shitty art and more inclined to discourage lousy politicians from becoming monsters hellbent on conquering the planet we’d be a lot better off.”

“True,” I said, “if Hitler’s artistic career had been allowed to continue and not been cut short there would be many more crappy oils of quaint churches at dusk and abandoned hay wagons at midday and misty covered bridges at dawn to clutter up the world, but at least there’d also be millions more Jewish doctors, dentists and psychiatrists to absorb all that mediocrity into gaudy frames in their waiting rooms.”

“What’s your book about,” asked a DNC canvasser with a clipboard and a blue T-shirt bearing the Obama logo just as the Pennsylvania sun was dipping behind the trees. He was watching me stack all my unsold books on my tiny table in preparation for returning them to the bookstore manager inside.

“Huh?” I said.

“Your book there,” he said. “What’s it about?”

“It’s a coming-of-rage book,” I said. He didn’t answer me. “It’s about how constructive nihilism can be when kept on the tip of a pencil and off the point of a fucking bayonet.” It had been a long day.

“You registered to vote?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said.

“You supporting Obama?” he said.

“Why?” I said.

“I just want to know.”

“No,” I said, “I mean why should I support him?”

“Forget it,” he said.

I did.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.