A Writer for All Time

Two new volumes -- a biography and an anthology -- shine light on G.K. Chesterton, an inhabitant of the twilight realm of the praised but unread.

“G.K. Chesterton, A Biography”

A book by Ian Ker

“The Everyman Chesterton” A book edited and with an introduction by Ian Ker

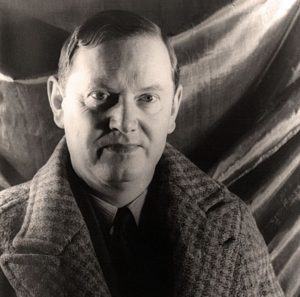

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, to paraphrase Georges Clemenceau on Brazil, is the writer of the future — and always will be. Over the years, I have made numerous friends with whom I had little else in common except a knowledge and affinity for the works of Chesterton. After we discovered Chesterton, we thought it just a matter of time before his clear-minded, unquenchable good will conquered the earth. It has never happened; it has never come close to happening, and in fact, in the 75 years since his death, Chesterton has become less of a major cult figure than an inhabitant of — and this phrase may have come from Chesterton himself, written in a notebook when I was in college and never pinned down — the twilight realm of the praised but unread.

Two huge new much-appreciated volumes — “G.K. Chesterton, A Biography” by Ian Ker (Oxford University Press) and “The Everyman Chesterton,” edited by and with an introduction by Ian Ker (Everyman’s Library/Alfred A. Knopf) — will not make Chesterton famous, though they go a long way toward bringing his life and enormous oeuvre into focus. (I’ve been working at reading all of him for nearly 35 years, and I have no way of knowing how close I am to completing the task.)

Born in Kensington, London, in 1874 into a middle-class family of secular liberals, GKC — as he was often referred to in the press — retained some of his parents’ principles, but as a young man he found liberalism to be thin soup for the soul. He became a Catholic convert in 1922, but to many friends, before and after, his lifelong temperament was constant. His religious faith was first expressed in “Orthodoxy,” published in 1908, which, wrote its author, was not “an ecclesiastical treatise but a sort of slovenly autobiography.” The book established the cornerstones of Chesterton’s philosophy, which were simple and enduring throughout his life: faith and patriotism.

Most people who recognize his name do so because of his ever-popular “Father Brown” mysteries, which still delight and have seldom been out of print. Then, of course, there is his most popular single work, the novel — or, as some prefer, fable – “The Man Who Was Thursday,” first published in 1908 and republished in at least three new editions on its centennial. And then, as several admirers have noted, he should be most famous for his journalism, for which he is now probably least well known.

G. K. Chesterton: A Biography

By Ian Ker

Oxford University Press, 688 pages

The Everyman Chesterton

By G.K. Chesterton (Author), Ian Ker (Editor, Introduction)

Everyman’s Library, 952 pages

The Rev. Ker, noted teacher of theology at Oxford and author of a superb biography of John Henry Newman, is, as we would expect, concerned largely with Chesterton the Catholic convert and apologist. This Chesterton’s most widely read volumes, “The Everlasting Man” — a book that had enormous influence on the century’s most influential Christian apologist, C.S. Lewis — “Orthodoxy” and biographies of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Thomas Aquinas, have never been allowed to go out of print by Catholic presses in Britain and the U.S.

“I think I can claim,” Ker writes, “to be writing the first full-length intellect and literary life of Chesterton.” Though I have not read a couple of others, including a much-praised work by Maisie Ward (which is roughly a third of the length), I’m going to let Ker’s claim stand without challenge. His book is simply too richly detailed and includes too much in-depth analysis to be challenged. For anyone interested in Chesterton’s Edwardian background and his intellectual, literary and religious development, “G.K. Chesterton, A Biography” will prove to be definitive.

Nor can it be said that Ker is not unmindful of Chesterton’s stature in other literary areas. He is a good critic, one capable of casting a cold eye on his subject. He is a bit puzzled that GKC is dismissed as a “minor writer” by many admirers of Newman, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin and Matthew Arnold. He is clear that Chesterton’s great literary works are not the once-famous novels and poems but “Charles Dickens,” “Orthodoxy,” “The Victorian Age of Literature,” “St. Francis of Assisi,” “The Everlasting Man,” “St. Thomas Aquinas” and the “Autobiography.” I intend to add to that list of secular titles later, but it’s clear that the religious books were Ker’s primary focus in undertaking this huge and impressive work.

This will no doubt satisfy many of the faithful, but there are a great many more of us who are interested in Chesterton for reasons other than his religious writings, and they may feel, as I often did, somewhat shut out of the discussion. Let me put it this way: Whatever Chesterton’s shortcomings as a writer, it’s doubtful that any 20th century author amassed such an amazing list of literary groupies. In fact, the roster of his most famous readers is nothing short of astonishing in its diversity.

George Orwell, whose thought was alien to much of the Catholic conservative principles of Chesterton, admired his integrity and his criticisms of both capitalism and socialism. Much the same could be said for H.G. Wells. “I love GKC,” Wells wrote, “and I hate the Catholicism of [Hilaire] Belloc. If Catholicism is still to run about the world giving tongue, it can have no better spokesman than GKC. But I grudge Catholicism GKC.”

George Bernard Shaw, a committed socialist and lifelong vegetarian who was as different from GKC’s beef and ale temperament as it was possible to be, nonetheless maintained a warm friendship with him, kept warm by their private and public debates. “I might say that [Chesterton] is seen at his best when he is wrong,” Shaw said. Ker states that GKC “had argued on practically every subject with Shaw … without ever quarreling.” Chesterton wrote a brilliant little book on Shaw, to which Shaw contributed the cover blurb: ” … the best work of literary art I have yet provoked.”

Belloc was impressed by his friend GKC’s characteristic mastery of paradox; William James found him to be, according to Ker, “a tremendously strong writer and true thinker, despite his mannerism of paradox.” Evelyn Waugh embraced the Catholic treatises but was put off by the gloomy foreboding of anarchism in “The Man Who Was Thursday.” T.S. Eliot saw a kindred spirit in the author who created the air of impending dread that pervades “Thursday.” Clive James loves his journalism. A lady once remarked to GKC, “You seem to know everything.” “On the contrary,” he retorted, “I know nothing, madam, I am a journalist.” Jorge Luis Borges, who did not care for journalism, was delighted by the cleverness of the detective stories. Wilfrid Sheed appreciated GKC’s utter lack of hyperbole when discussing the most heated social and political issues of his century.

Michael Collins — yes, that Michael Collins, the revolutionary who made modern Ireland, was an avid reader of the novels, particularly “The Napoleon of Notting Hill” and “The Man Who Was Thursday,” books that, among other things, taught him the lesson that, as one commentator put it, “If you don’t seem to be hiding, nobody hunted you out.” According to Ker, Lloyd George gave copies of Chesterton’s novels to his cabinet members before they negotiated with the Irish rebels. “For insights into the mind of the Irish nationalist leader,” he said.

Chesterton also had his critics. Ezra Pound once grumbled that “Chesterton is the mob.” Ker answers the charge: “He was … a solitary defender … of the despised suburbs where the masses lived.” His influence has emerged in the most unlikely places: a young Czech writer, Franz Kafka, thought Chesterton “so happy that one might almost believe he had found God.” Neil Gaiman, the most popular graphic novelist in the world, paid him homage with the character Gilbert in his “Sandman” series.

For me, the problem with “G.K. Chesterton, A Biography” is that I don’t think Ker cares all that much about Chesterton’s relevance to the modern age. The question inevitably arises: Was Chesterton, by our standards, a conservative or a liberal?

Our standards, I’m afraid, would have elicited nothing but contempt from him. As he wrote in an essay in 1929, “The business of the Progressives is to go on making mistakes, while the business of Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected.” The real problem with conservatism, he thought, is that it is “based upon the idea that if you leave things alone, you leave them as they are. But you do not. If you leave a thing alone, you leave it to a torrent of change.” If forced to choose, he probably would have opted for traditionalist: “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead.”

He was a witty and unsparing critic of both socialism and capitalism; he actually wrote for a socialist paper, The Daily Herald, for a time because the editors gave him the freedom to attack socialism in front of a readership prepared to disagree with him.

It was, however, his criticism of capitalism that earned him some of his most fervent friends and enemies and has kept him at arm’s length from modern conservatism. As GKC famously wrote, “Modernity is not democracy; machinery is not democracy, the surrender of everything to trade and commerce is not democracy. Capitalism is not democracy; and is admittedly, by trend and savour, rather against democracy. Plutocracy by definition is not democracy.” Unlike his conservative friends, he made a sharp distinction between private enterprise and private property: “A pickpocket is obviously a champion of private enterprise, but it would perhaps be an exaggeration to say that a pickpocket is a champion of private property.”

G. K. Chesterton: A Biography

By Ian Ker

Oxford University Press, 688 pages

The Everyman Chesterton

By G.K. Chesterton (Author), Ian Ker (Editor, Introduction)

Everyman’s Library, 952 pages

Chesterton’s definition of patriotism often conflicted with that of his contemporary, Rudyard Kipling (both died in 1936). The poet laureate of the British Empire, Kipling was contemptuous of his native country; Chesterton, the apostle of smallness, loathed the empire — he opposed the Boer War and was outspoken for Irish independence — while loving England with a passion that would have made Dickens blush. Ker quotes a contemporary: “He knew nothing so vulgar as that contempt for vulgarity which sneers at the clerks on bank holiday or the Cockneys on Margate sands.”

Unfortunately for the 21st century, Chesterton never truly developed his political philosophy, Distributism, beyond his 1926 book, “The Outline of Sanity,” which advocated the spreading of wealth — attention, President Obama! — through simple measures such as boycotting big stores and creating laws geared to the establishment of small shops.

William F. Buckley loved Chesterton the Catholic but not the progressive thinker; in his recent memoir, “Outside Looking In,” Garry Wills recalls that “when [Buckley] asked me at our first meeting if I was a conservative, I said, ‘Is a Distributist a conservative?’ Buckley replied, ‘Alas, no.’ ” (By the way, Wills’ 1961 book “Chesterton,” remains one of the best analyses of Chesterton’s political and economic thought. I’m hoping that Wills will follow up and elaborate on Chesterton’s political and economic ideas.)

None of GKC’s political writings nor his fiction, except for an excellent selection of the “Father Brown” stories, is represented in “The Everyman Chesterton.” The anthology is nearly as long as the biography, and considering that it contains thick portions of his hard-to-find studies — “Dickens,” “The Victorian Age in Literature,” “The Everlasting Man,” “Orthodoxy ” and “St. Thomas Aquinas” — “The Everyman Chesterton” is a terrific bargain. Two out-of-print but easy to find earlier collections — “The Man Who Was Chesterton” (1960) and “A Chesterton Anthology” (1985, selected and introduced by P.J. Kavanagh) — are, to my mind, more rounded expressions of Chesterton’s genius (for one thing, both contain numerous excerpts from his critical essays and political journalism).

Both “G.K. Chesterton, A Biography” and “The Everyman Chesterton” will be huge favorites of any lover of the man. What is less likely is that they will make Chesterton lovers of novices. However readers choose to make their entrances into the world of GKC, they are advised to jump in. But be wary: The pool is very big. Our greatest living cultural critic, Clive James, wrote in “Cultural Amnesia,” “My shelves containing Chesterton still outdistance my shelves containing Edmund Wilson, but with Wilson I know my way around almost to the inch, whereas there are cubic feet of Chesterton’s output where I can’t find my way back to something I noticed earlier. …” James also said, “Catching up with Chesterton’s prose is the work of a lifetime. He wrote a lot faster than most of us can read.”

Try the above mentioned anthologies or, for that matter, any book by Chesterton. “If a key fits a lock,” he wrote in “Orthodoxy,” “you know it is the right key.”

Allen Barra is a regular contributor to The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post Book World, and Bookforum and a contributing writer for American Heritage and The Village Voice.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.