A World Without Words

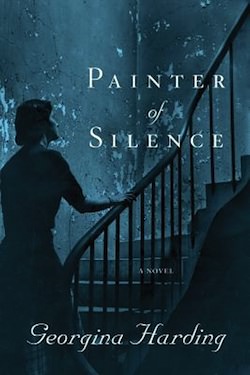

Georgina Harding's "Painter of Silence" is a disturbing portrait of war, seen through the eyes of a deaf artist.Georgina Harding's novel "Painter of Silence" is a disturbing portrait of war, seen through the eyes of a deaf artist.

“Painter of Silence” A book by Georgina Harding

In “Painter of Silence,” Georgina Harding has written a touching and disturbing portrait of war and those who are affected by it. The setting is early 1950s Romania, after the ravages of World War II. The central character is Tinu, an artist who cannot hear or speak. He uses the language of images to communicate with the world and to make whatever limited sense of it he can.

The novel opens with Tinu on the verge of death. He has survived the loss of his home and all that is familiar, but he is now little more than a ruined shadow. He arrives by train at a city that is nothing but

“black smears of road, grey walls, grey buildings angled across the sides of hills. The buildings appeared singly at first then massed, most of them solid but some hollow so that he could see through them to the sky as it darkened. Between the buildings there were the bare outlines of trees — still there were trees — but the forest was gone.”

The reader is not told where he has come from, but we realize he has never seen a city before. Apart from that we know only that he is searching for Safta. Tinu is the illegitimate son of the cook at a great country manor, and Safta was the aristocratic daughter who was kind to him as he grew up. It was she who understood him when no one else could, who tried to cross the boundary of his silence, and discovered his talent for painting. Because Tinu seemed to understand so little of what he drew, and because of his stubborn nature, all efforts to educate him failed, and he was left to take care of the family’s horses. He found comfort in the stable and a modicum of peace.

Tinu’s search for Safta seems like a holy quest, for to find her is to find home, and that is all he really comprehends. Tinu is stubborn but not terribly assertive. He is an innocent, and in this holy quest, might be seen as the original definition of the holy fool — a simple person, perhaps, but one endowed with great spiritual wisdom.

The peace that Tinu finds with the horses is destroyed by the advent of war. It is a phenomenon that is utterly inexplicable to Tinu. He sees only the senseless barbarity, including the killing of a Lipizzaner stallion he loved, and it is through his senses that the reader experiences the enormous stupidity, the utter inane savagery, of war.

The story shifts back and forth between prewar Poiana — Safta’s family’s light-filled estate — and the bleak postwar town of Iasi, where once-elegant mansions are now chopped into tiny apartments crammed with damaged survivors. Safta is a nurse in the hospital where Tinu is taken after he collapses. She brings him paper and pencil, and he begins to heal and to draw again. Slowly the mystery of what happened to Tinu, and to Safta, begins to unfold.

Author Georgina Harding says in her acknowledgements that the character of Tinu was inspired by James Castle (1899–1977), an Idaho artist who could not hear or speak, and was probably autistic. The Philadelphia Museum of Art says of Castle that “despite undergoing no formal or conventional training, [he] is especially admired for the unique homemade quality, graphic skill, and visual and conceptual range that characterize his works. By all accounts deaf since birth, and presumably never having learned much language, Castle turned his obsessive and constant production of drawn images into his primary mode of communication with what must often have seemed the strange and baffling world around him.”

|

To see long excerpts from “Painter of Silence” at Google Books, click here. |

This certainly describes Tinu, and in fact the idea that Castle may have been autistic lends understanding to Tinu’s responses to the world. Much of the book is told from his point of view in free indirect discourse, and this is a bit problematic. Although Tinu is a fascinating character and a splendid symbol of baffled innocence and stubborn life force, a book depends on language. The fact that Tinu really has no language is awkward. He does not read lips. He has no sign language. He is utterly locked into his silent world. There is a moment when, as the enemy forces approach Poiana, Tinu has been instructed to pack up the family’s belongings. We are told he

“packed everything with his customary careful touch, wrapping tissue about china vases and dishes and figurines. As he packed he pictured the servants in that other house unwrapping the figurines and arranging them on other shelves: a shepherdess, a harlequin, a goddess.”

First, how would he understand that the household is moving and that what is being packed is intended to be unpacked somewhere else? No one would be able to tell him so. Second, how on earth would he have words for “shepherdess,” “harlequin” or most of all, “goddess”? The same is true when he thinks of war in general. How would that complex idea form in his mind? As chaos, as strange men, as death and killing, perhaps, but I am not convinced, since we are told he has only a few nouns, that he would understand the concept of war. One has to suspend disbelief for any of the sections written from Tinu’s point of view to work, of course, but sometimes I felt Harding asked too much in this regard.

Like Tinu himself, this is a quiet book, full of well-crafted, precise lyrical language. Harding chooses simple words, but she selects them so carefully that the impression is poetic. She is exploring dislocation, loss, memory and the relationship between language and story. “Didn’t he understand about the past?” Safta wonders about Tinu at one point. “She had thought, perhaps you needed words for that, to pack time away, to file and classify events and sort them into history. Words made it possible to say: This happened then. That is finished. Here is now. But it isn’t so.”

Harding makes wonderful use of symbols, and none more so than the sacred communion of food. Throughout the book meals are shared, but toward the very end there is a perfect moment when Tinu and Safta and a third character I will not name for fear of spoiling things for the reader, preserve some plums, cooking them in wine that has been hidden behind a wall throughout the war. The act of preserving the sweetness of the present moment in the wine of the past, for the journey of the future, is succulently written.

“Painter of Silence” was shortlisted for the 2012 Orange Prize for Fiction, and deservedly so.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.