A Short History of Eugenics: From Plato to Nick Bostrom

The idea of selective human breeding is as enduring as it is dangerous. Marble busts of Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle / CC

This is Part of the "Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century: New Names, Old Ideas" Dig series

Marble busts of Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle / CC

This is Part of the "Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century: New Names, Old Ideas" Dig series

In a previous article for my Dig series, I described an “ethical” framework called longtermism as yet another example of the “eternal return of eugenics,” borrowing a phrase from Jean Gayon and Daniel Jacobi. To better understand what this means, and why the “eternal return” of this idea is so powerful, let’s take a closer look at the history of eugenics, from ancient origins to contemporary incarnations.

When most people hear the word “eugenics,” they immediately think of the Nazis. And for good reason: the Nazis force-sterilized over 400,000 people and brutally murdered another 300,000, all in the name of a particular approach to eugenics called “racial hygiene.” Yet the truth is that eugenics captured the imagination of people on both sides of the political spectrum. This included progressives across Europe and North America, many of whom saw it as playing an integral role in progressive social reform.

Eugenics isn’t a new idea. Though the term itself was coined in 1883, proposals for improving the “human stock” through methods like selective breeding dates back at least to the ancient Greeks. Eugenics practices — often based on what we now describe as “ableist” beliefs — have been common throughout history. It is a monster that just won’t die, no matter how many times people have tried to bury it.

One of the earliest discussions of eugenics comes from Plato’s “Republic.” In outlining what a just city-state would look like, Plato’s fourth-century B.C.E. treatise proposed a rigged lottery to grant superior members of the ruling class — called the “guardians” — a greater opportunity to procreate.

One of the earliest discussions of eugenics comes from Plato’s “Republic.” In outlining what a just city-state would look like, Plato’s fourth-century B.C.E. treatise proposed a rigged lottery to grant superior members of the ruling class — called the “guardians” — a greater opportunity to procreate. The offspring of those deemed “inferior” would then “be secretly taken away by officials and almost certainly left to die, along with the visibly defective offspring of the superior guardians.” Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle, proposed a somewhat similar idea, arguing for the use of abortion to prevent parents from having too many children, while endorsing infanticide “for any children born with deformities.”

Thusly does Western philosophy begin: with a couple of eugenicists. This becomes less surprising the deeper you dig into its enduring influence.

Athens wasn’t the only place in the ancient world where people thought about and practiced eugenics. Several centuries before ancient Rome became an empire, the so-called “Twelve Tables” of Roman law “made provisions for infanticide on the basis of deformity and weakness.” Here’s what Seneca, the philosopher and adviser to the emperor Nero, had to say:

We put down mad dogs; we kill the wild, untamed ox; we use the knife on sick sheep to stop their infecting the flock; we destroy abnormal offspring at birth; children, too, if they are born weak or deformed, we drown. Yet this is not the work of anger, but of reason — to separate the sound from the worthless.

During the Enlightenment, eugenics experienced a revival as some philosophers began to fret about children produced by interracial couples, worrying that miscegenation — sexual relations or marriage between people of different “races” — could corrupt European bloodlines and “produce disfigured children.” One influential theory of the origins of nonwhite races posited that all humans were initially white, and that over time, different groups “degenerated” into the “races” currently observed in the world. This idea was dominant idea around the time the transatlantic slave trade peaked, and used as a justification for the enslavement of Africans across the Americas.

The notion that eugenics is based on “reason” or “rationality” grew sharper into the modern era, as eugenics came to be seen as a thoroughly scientific endeavor. This form of eugenics was greatly influenced by Francis Galton’s 1863 book ”Hereditary Genius,” which drew from the evolutionary theory of his cousin Charles Darwin. Galton argued that if people with more “desirable” traits were to outbreed their inferior peers, then these traits would become more common in the population; and if such traits were to become more common, it would spur human “greatness” and “genius.” This idea quickly gained traction, boosted in part by widespread fears in the late 19th century of evolutionary “degeneration,” a possibility most famously explored by the eugenicist H. G. Wells in his 1895 book “The Time Machine,” which imagined the human species degenerating into two subhuman creatures: the Eloi and Morlocks.

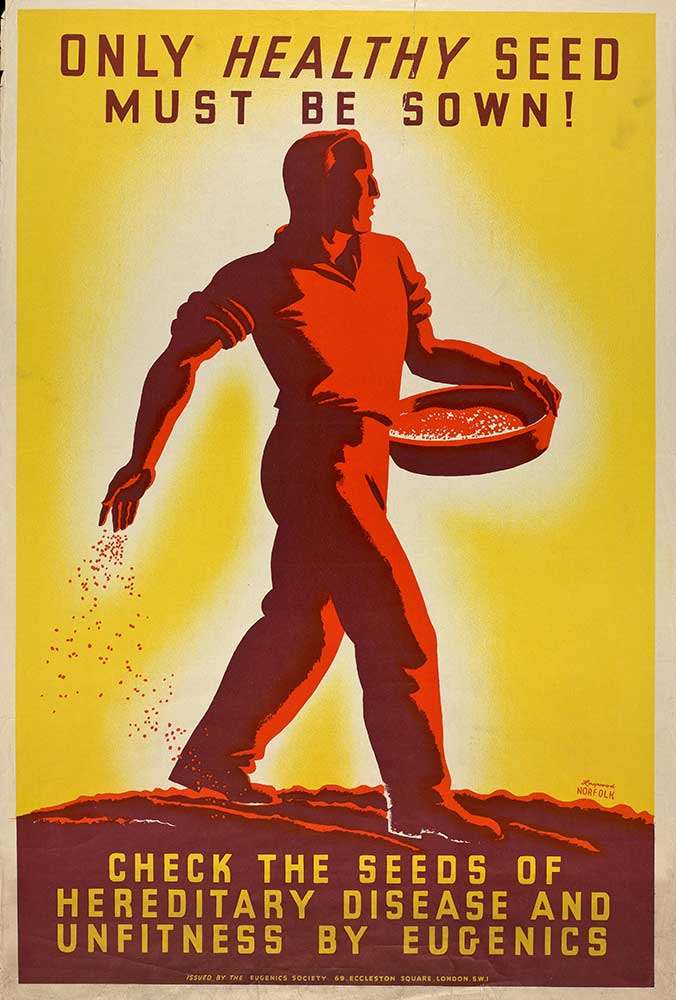

During the early decades of the 20th century, eugenics was widespread in the United States, peaking in the 1920s. American-style eugenics took two forms. Positive eugenics encouraged “superior” people to have larger-than-average families, thereby increasing the frequency of their “desirable” traits within the population. This is essentially what Galton proposed, and it inspired a wave of “better baby” and “fitter family” contests across the country. Negative eugenics, on the other hand, aimed to prevent those deemed “unfit” or “feeble-minded” from reproducing. But how could this be accomplished? What if the “unfit” decided not to listen? The answer was a number of forced-sterilization programs that states like Indiana and California implemented, the latter of which sterilized some 20,000 people against their will between 1909 and 1963 — although California’s eugenics program didn’t officially end until 1979.

During the Enlightenment, eugenics experienced a revival as some philosophers began to fret about children produced by interracial couples, worrying that miscegenation — sexual relations or marriage between people of different “races” — could corrupt European bloodlines and “produce disfigured children.”

This program was a major inspiration for the Nazis, who studied it carefully in designing their more aggressive version of the program in Germany. While “eugenics” often conjures up images of the Nazi’s brutal crimes against Lebensunwertes Leben — a German phrase meaning “life unworthy of life” — the fact is that their “racial hygiene” policies were based on a system implemented in the democratic U.S. during the Progressive Era. (Albeit with a 19th-century flourish: Hitler’s deputy Führer described the Nazi program as “applied biology.”)

One might think — and hope — that the atrocities committed in Germany during the 1930s and 1940s would have ruined eugenics as a credible idea worthy of serious consideration as the basis of public policy. But eugenics, rather than being jettisoned entirely from the ship of society, persisted and even flourished around the world in the postwar era. In fact, some countries implemented such programs for the first time after World War II. Sterilization rates actually increased in Denmark and Norway after the Nazi occupation of these countries came to an end, and more than 55,000 people were surgically sterilized in Finland between 1951 and 1970. Sterilizations in Canada didn’t end until 1971; in Sweden they continued until 1975. As mentioned, they persisted under California law until 1979. On the other side of the planet, Japan implemented its “Eugenic Protection Law” in 1948, which enabled the compulsory sterilization of over 16,500 people between 1948 and 1996, when the law was finally repealed. This is why historians talk about the “continuity” of eugenics throughout the 20th century.

The waning decades of the 20th century also witnessed the rise of a new version of eugenics: so-called “liberal” eugenics. This was the result of novel developments in fields like genetics, which led some to speculate about the possibility of parents selecting the characteristics of their children through genetic engineering techniques, resulting in what were popularly called “designer babies.” The reason this was called “liberal” — in contrast to the “authoritarian” eugenics of earlier times — is because it would, supposedly, empower parents without state coercion to decide the genetic characteristics of their children. Whereas the old eugenics required changes in society-wide patterns of reproduction to work — these changes being coordinated from the top-down, through interventions like forced-sterilization — improving the human stock through genetic engineering required no such thing. Over a single generation, even parents with “undesirable” traits could create children with super-high “IQs,” exceptional athletic abilities, or whatever attributes they believe would help their offspring succeed in the world.

Some people even began to imagine how advanced technologies could enable us to modify ourselves, within our own lifetimes, to acquire super-human capacities, resulting in a superior new race of “post-human” creatures. While earlier eugenicists hoped to fend off degeneration and perfect the human species, these transhumanists argued that “radical enhancements,” made possible by “person-engineering” technologies, could make it possible for us to transcend the human realm altogether. The outcome could be, they claimed, a literal “Utopia,” as described in a short essay titled “Letter from Utopia” by the prominent transhumanist Nick Bostrom. As it happens, Bostrom is highly influential among the contemporary eugenics movement that calls itself “Rationalist,” and is co-founder of the longtermist movement that is the focus of this series. Indeed, the longtermist worldview has been crucially shaped by transhumanism, the most notable instance of contemporary “liberal” eugenics. This is why (at least in part) I have argued that longtermism — an ideology promoted by tech billionaires like Elon Musk and increasingly embraced by influential figures within major governing bodies such as the United Nations — should be seen as the iteration of the “eternal return of eugenics.”

While “eugenics” often conjures up images of the Nazi’s brutal crimes against Lebensunwertes Leben — a German phrase meaning “life unworthy of life” — the fact is that their “racial hygiene” policies were based on a system implemented in the democratic U.S. during the Progressive Era.

Dating to the ancient Greeks, practiced by the Ancient Romans, animating the concerns of the Enlightenment, acquiring the appearance of legitimate science in the 19th century, responsible for some of the worst atrocities of the 20th, revived today by transhumanists and longtermists — across Western history, from one side of the political spectrum to another, eugenics is a specter that keeps on haunting our world. Indeed, there is no reason to believe that eugenics won’t continue to shape society, and cause new and profound harms, in the coming decades.

The most insidious aspect of this perpetual recurrence is that each new iteration makes the same promise: That it won’t be like the last. This time it’s founded on scientific principles; this time it’s purged itself of the discriminatory attitudes that inspired earlier eugenicists — racism, xenophobia, ableism, classism, sexism, and so on. As I showed in my previous article, the contemporary longtermist community is rife with precisely these attitudes. But history justifies skepticism of such assurances. My next article will examine the inherently eugenicist aims of longtermism, and show why its promises are not to be trusted.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

Surprised you didn't cite Madison Grant's "Passing of the Great race" which led directly to the 1924 immigration act with severe restrictions on immigration from S. Europe (Italians) E. Europe (Jews & Slavs) as at the time these people were not considered white. It also results in over 2MM Italians being deported.

When Torres lists all the isms he’s against, he implies that if only people thought differently the glorious egalitarian utopia would appear overnight. But it doesn’t matter how we think, no two people will still be equal in any way. Everything he writes implies genetics doesn’t stand in the way of equality. But no matter how we think, will a baby born without a brain be as smart as Einstein? Will a baby born without...

When Torres lists all the isms he’s against, he implies that if only people thought differently the glorious egalitarian utopia would appear overnight. But it doesn’t matter how we think, no two people will still be equal in any way. Everything he writes implies genetics doesn’t stand in the way of equality. But no matter how we think, will a baby born without a brain be as smart as Einstein? Will a baby born without legs run as fast as Usain Bolt? The myth of equality is, to my mind, merely a secularized version of the Christian belief in souls equal in the eyes of God. To me, the current fervent belief of the university-educated ruling class in the myth of equality makes this as deeply religious a period as the middle ages. Or another phase of American religious revival like the four Great Awakenings.

But, you know, when you decide to mate with someone better looking and smarter than someone else, you’re practising eugenics. When you work hard to increase your income so you can afford another child someone else can’t afford, you’re practising eugenics. And, needless to say, if you abort a fetus with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) you’re practising eugenics. Is the left going to ban all that? Probably – that’s the only way it can force...

But, you know, when you decide to mate with someone better looking and smarter than someone else, you’re practising eugenics. When you work hard to increase your income so you can afford another child someone else can’t afford, you’re practising eugenics. And, needless to say, if you abort a fetus with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) you’re practising eugenics. Is the left going to ban all that? Probably – that’s the only way it can force humanity into the Procrustean bed of equality. The left eugenicists of the early 20th century like HG Wells, Margaret Sanger, Marie Stopes, Nellie McClung were at least trying to come to grips with the world-shattering discovery of evolution and genetics. Today’s left just completely ignores it – and Torres is a prime example. That’s why leftists don’t even notice complete contradictions in their thinking. They currently claim that sex, despite being controlled by entire chromosomes, is so superficial that it can be changed overnight. Yet they simultaneously claim that sexual orientation is, apparently, 100% genetically controlled, because they believe that it can never be changed and have even made it a legal crime to try.