A Reporter Who Covered the Watts Riots 50 Years Ago Today Looks Back

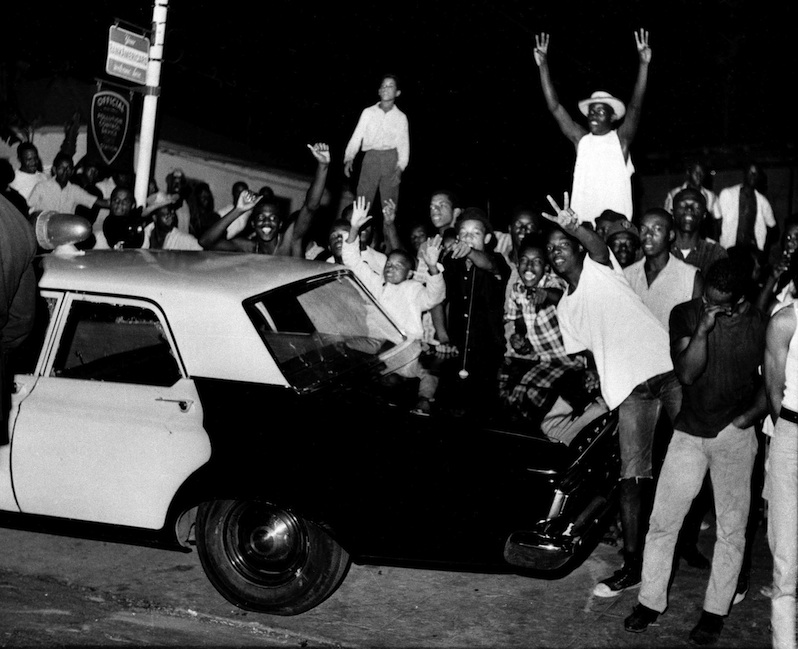

A first glance at seemingly normal neighborhoods did not reveal the oppression and angst that had fueled one of the most violence uprisings in U.S. history. One had to probe deeper to find that raw nerve. Demonstrators push against a police car after rioting erupted in a crowd of 1,500 in the Watts area of Los Angeles on Aug. 12, 1965. (AP)

Demonstrators push against a police car after rioting erupted in a crowd of 1,500 in the Watts area of Los Angeles on Aug. 12, 1965. (AP)

I was one of the large number of white reporters who covered the Watts riots a half century ago, unaware of the causes of the terrible events unfolding before our eyes.

Newspaper editors and reporters—and newspapers were the dominant media of the day—were almost all white. Our ignorance of African-American life was profound. That was the case in Oakland, where I started out, as well as in Los Angeles and the rest of the urban West and the North—sections of the country that liked to congratulate themselves for being more racially tolerant than the South.

I was with The Associated Press in Sacramento in August 1965 when the riots broke out, and I was dispatched to Los Angeles to help with the coverage. My first impression of South Los Angeles was superficial and wrong. I saw block after block of single-family homes, California bungalows, mostly well tended, that reminded me of neighborhoods in Oakland. I wondered why there would be riots in Watts—violence that ended up killing 34 and injuring more than 1,000.

I knew nothing of the long history of residential and school segregation that preceded the riots or of the years of brutal and racist law enforcement by the largely white Los Angeles Police Department. Nor did I know of the closing of tire and auto plants and other factories that left so many South L.A. residents jobless.

My friends were impressed by a Newsweek account that had me calling in a story from a phone booth as it was under siege by African-Americans. If this happened to someone, it wasn’t me. But I was on the streets and did have an encounter that greatly added to my knowledge of South Los Angeles.

I was working with another white AP reporter, Jim Bacon, who was acclaimed for his coverage of his usual beat, Hollywood. We had been assigned to interview Watts residents. Bacon usually hung out with big stars like Sinatra and Marilyn Monroe, yet he was as comfortable in Watts as he was in the bar of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

We got out of our car and walked around in territory that was unfamiliar to both of us. Notebooks in hand, we began to interview people. Soon we were surrounded by several young black men. Jim, always genial, began talking to them, and they told him their grievances. He was relaxed, respectful and interested in what they had to say. I was impressed by his demeanor and learned an invaluable lesson on being a reporter in a potentially tense situation.

Many of their grievances centered on the Jewish merchants who owned several nearby stores—at that point destroyed by fire—and who drove what the young men called “Jew Canoes.” What’s that? I asked. A Cadillac, they explained before continuing their verbal attack on Jewish merchants. I interrupted and said I was Jewish. Not all Jews were bad, they said, and they pointed out a few Jewish-owned stores that had been spared. Bacon and I wrote our story, using the phrase “Jew Canoe.” The San Francisco Chronicle ran it on Page 1, and my father, upon reading it, called me, angry about the phrase. “They’ve got more of them [Cadillacs] than we do,” he insisted.

The article may have been one of the few at the time pointing out black anti-Semitism and the economic grievances that were one of the riots’ causes.

Yet within eight years, Tom Bradley, an African-American city councilman, would be elected mayor in a city that was largely white, forging a coalition of blacks, whites, Latinos and Asians. As I wrote last week on the website LA Observed, he “brought the city together, as King Arthur sang in Camelot, ‘for one brief shining moment,’ and then saw it crumble in fire and death during the 1992 riot.”

By 1970, I was on the Los Angeles Times staff and I explored the streets, politics, businesses, churches and organizations of South L.A. The place was changing. Korean-American business owners replaced the Jews of the ’60s. Latinos moved into neighborhoods that had once been exclusively African-American. The riots that occurred in 1992 were a truly integrated conflagration.

I wanted to know more about the history of race in Los Angeles. I was researching my book “Big Daddy: Jesse Unruh and the Art of Power Politics,” about a famous and powerful California politician, and was studying the area Unruh had represented in the state Assembly. It had been at the center of violent white resistance to African-Americans trying to move out of the miserably overcrowded Central Avenue area.Latinos, Asian-Americans and sometimes Jews were also targets of this kind of segregation. “Is it a crime in America for a Negro, or Jew, or Mexican or Chinese to live next door to a man who is none of these?” wrote Charlotta Bass, the courageous owner of the California Eagle, an African-American community newspaper. But African-Americans had it particularly bad, probably because they were at the cutting edge of the fight against housing segregation.

I knew there had been trouble in the post-World War II years, but the mainstream newspapers had published little about it. Only in old copies of the Eagle and another African-American paper, the Sentinel, and the Communist Party paper the People’s World did I find out the intensity of the struggle.

War veteran Henry Laws, his wife and a daughter were jailed for refusing to vacate a home they had bought in a white neighborhood. A cross was burned on a physician’s lawn when he tried to move west of the Figueroa Street color line. Neighbors trashed a black-owned home in white Leimert Park, a neighborhood later integrated by Tom Bradley. Bombs shattered another home in similar circumstances. Rocks were thrown at a black-purchased home in View Park. And there were other cases.

And where could the victims go for help? To a police department under the dictatorial, racist command of Chief Bill Parker?

Why were there riots in 1965 and 1992? Why not?

Are things better than they were in August 1965? Or worse?

The manufacturing jobs have not returned. The post-Watts resurgence of markets and other retail businesses suffered a setback in the 1992 violence. The public schools struggle to send students to the universities, where they could have a chance to move up the ladder. Racial discord and racism are always under the surface. Poverty, unemployment, homelessness and lack of opportunity persist.

Still, Los Angeles has improved.

Latinos, blacks and Asian-Americans are in positions of political power. City Hall, now multiethnic, is a far different place than it was in 1965.

The Los Angeles Police Department is better. It’s integrated, more suited for a city in which people of color now make up a majority of the population. Two reform chiefs, Bill Bratton and now Charlie Beck, have rooted out the racists and the criminal cops who shook down Salvadoran immigrants in the LAPD’s Rampart Division. Cops are told to actually talk to residents instead of treating them as if they were disenfranchised residents of an occupied country.

Improvements, unfortunately, are measured in inches in the United States. By that standard, Los Angeles has come a long way since 1965. But it has a longer way to go.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.