A Racist Mecca, a Black Architect and Odious Politics That Refuse to Die

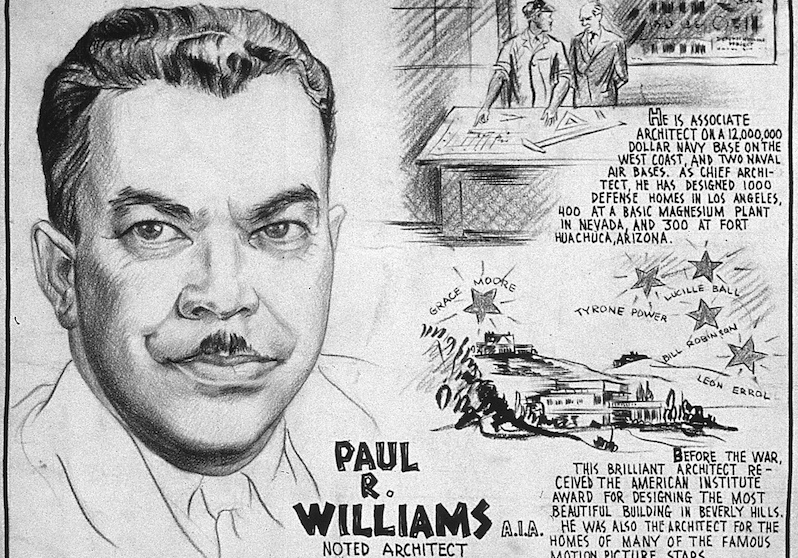

“Blueprint for Paradise,” in its world premiere in Los Angeles, is powered by an odd, real-life California tale of a pre-war Nazi center and its acclaimed designer, Paul Williams Sadly, the political rot explored by the play survives: Check out the 2016 presidential campaign “Blueprint for Paradise,” in its world premiere in Los Angeles, is powered by an odd, real-life California tale of a pre-war Nazi center and its acclaimed designer, Paul Williams. Poster from the Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, 1943. (Charles Alston)

Poster from the Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, 1943. (Charles Alston)

Poster from the Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, 1943. (Charles Alston)

He was a rarity in 1940: a successful African-American architect in Los Angeles. Paul Revere Williams built some of the city’s most famous structures — the Superior Court building downtown, the futuristic Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport — as well as private homes for celebrities including Lucille Ball, Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Sinatra.

Despite his success, he battled racism throughout his career, growing used to the surprised expression of new clients whose enthusiastic embrace became less so after finally meeting him face to face — clients like Clara Taylor, the right-winger at the center of “Blueprint for Paradise,” a play getting its world premiere at the Hudson Theatre in Hollywood.

Based on one of the oddest chapters in Williams’ career — the time when he designed and built a compound for the Silver Legion of America, a Nazi group also known as the Silver Shirts — the play, by playwright Laurel M. Wetzork and director Laura Steinroeder, shrewdly incorporates real-life fascist movements with ideological components espoused by major public figures of the time. Based on fact and local legend, “Blueprint” is set in Rustic Canyon in Pacific Palisades, where, it was recently announced, the final remains of the 55-acre Murphy Ranch, including a power station, a buckled fuel tank, a collapsed shed and garden bed foundations, are to be demolished.

In its time Murphy Ranch was the hopeful beginnings of a Nazi mecca, with an elaborate infrastructure accommodating a 20,000-gallon fuel tank, a power station and a 395,000-gallon concrete water tank. A bomb shelter, bunkers and a garage were completed, but unrealized were plans for a four-story, 22-bedroom mansion with an indoor pool and servants’ quarters. It was meant to become Nazi headquarters in North America after a victory that Germany was expecting in Europe turned the United States into a war zone.

At one time the hillside above the ranch was terraced, with a sprinkler system on timers for irrigating a wide variety of fruit, olive, nut and carob trees. Financing the creation of the compound were heiress Winona Stevens and her husband, Norman, an engineer with interests in the Colorado silver trade. They were influenced by a German with the dubious moniker Herr Schmidt, a probable conduit to Nazi money.

Modeled after Hitler’s Brown Shirts, the Silver Shirts originated in North Carolina under the leadership of founder William Dudley Pelley, a journalist, former screenwriter of Lon Chaney movies and, after a near-death experience, fascist guru mystic. At its height in 1934, the group counted 15,000 members. But once war against Germany was declared, the pro-Nazi organization saw its ranks steadily diminish.

Though Winona Stevens — “Clara” in the play — was not a member of the Mothers’ Movement, her onstage counterpart is. A real L.A.-based group of mostly middle-class, white Christian women, the Mothers advocated for right-wing causes and isolationism. Numbering in the millions with chapters in most states, many members were arrested in 1942 in an effort to stamp out burgeoning anti-Semitic and fascist movements.

As played by Meredith Thomas, Clara’s primary concern is to maintain safe streets—the character had lost a child to violence—and to protect young lives by keeping the U.S. out of the war, motivations that make her a perfect fit for both the Mothers’ Movement and the Silver Shirts, who promise to cleanse the streets of genetically sketchy undesirables. For Clara, the fact that they are fascists is beside the point.

“She’s very protected by her husband,” says Wetzork, “—[a husband of the sort] who, when women were considered hysterical, got prescriptions for drugs to calm them. So she’s sort of battling that and thinks her husband is perfect and absorbs what he says.”

While researching the play, Wetzork found that concern over nonwhites “invading” the country and the denigration of minorities were about as virulent then as now. “… [T]here are too many, too many dirty bean-eaters,” says Herb Taylor, Clara’s husband, played by David Jahn. “If we don’t stop them soon, they’ll swarm and devour the earth, like locusts!”

Director Steinroeder hears echoes of this sentiment in the 2016 presidential race. “We’re finding all these really scary parallels with our current political state and what was going on in 1941, groups of people with so much hatred,” she observes. “I’ll be giving an actor direction and I’ll start off by saying, ‘In 1942 a black man …’ and then realize the same applies to 2016.”In the play, Wetzork has made Clara’s husband a member of the Human Betterment Foundation, an organization dedicated to eugenics, which was popular among intellectuals and civic leaders including then-Los Angeles Times Publisher Harry Chandler and Nobel Prize-winning physicist Robert Millikan. Along with the work of like-minded organizations, the foundation’s studies on human sterilization inspired Hitler’s plans for a racially pure society.

On Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, FBI agents occupied Murphy Ranch. Fifty people were arrested, including Herr Schmidt. But the Stevenses, claiming they were victims of the Nazis, were soon released and remained on the ranch until its sale in 1948.

In the play, Clara is duly impressed by Williams’ blueprints for the compound, but in reality it remains a mystery why the Nazis would trust a black man with such an expensive commission. Maybe it had to do with the recent opening of his Saks Fifth Avenue building in Beverly Hills, or maybe it was a question of cost. There are few mentions of the ranch in Williams’ notes — what remains of them after the fires of the 1992 L.A. riots. Up until the time of his death in 1980 he claimed he never knew who his clients were until the ranch’s climactic end. “I had no idea this was going on,” he wrote in his diary after the FBI raid. “I was simply caught up in designing an exquisite 40,000-square-foot home!”

He was caught up with plans that never got off the drawing board. And beyond razing the remaining structures last spring, the state Parks Department has not yet said what it will do with the ranch.

Meanwhile, there have been reports as late as June that the barn is still there, boarded up, and the powerhouse too, coated in street art, a gloomy splash of color in the heart of Nazi paradise.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.