A New Front in the War on Terror

In an attempt to promote international understanding, the Jaipur Literature Festival fights against “the terrorism of the mind,” said the event's producer, Sanjoy Roy.

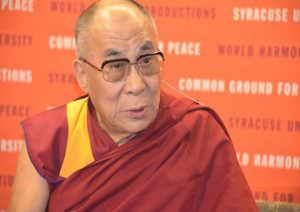

JAIPUR, INDIA — So into a bar walk a Palestinian-British novelist, a famous Jewish humorist and an Indian cricket star. On nearby barstools are an Academy Award-winning Pakistani filmmaker and a gay writer on psychology. Add a Bollywood celebrity, an Argentine dissident, the Dalai Lama and—what the hell—a few Bhutanese literary pioneers. Ready to break a brawl is a crusading Indian investigative journalist who has written one of the sexiest novels of all time. Of course there’s a guy from Google, helping to underwrite the scene.

This is way too complicated for a bar joke and unfortunately, at least in the opinion of some of the writers, the scene wasn’t a bar. The Jaipur Literature Festival held from Jan. 24-28, 2013 at Diggi Palace, was alcoholically as dry as a bone. But it was extraordinarily rich in ideas, not to mention in chai, peddled by wallahs pouring milky sweet caffeine into clay cups, 20 rupees, madam.

There is a new front on the war against terrorism: the international literary festival. The Jaipur festival presented 260 authors, many from nations that are enemies more than drinking buddies—or are, as speaker Reza Aslan said about the United States toward Pakistan, in “incredibly schizophrenic” relationships. The authors spoke to 130,000 attendees, about half local Rajasthanis (Jaipur is the capital of Rajasthan state), a quarter from greater India, and the rest from the wider world, as estimated by co-director and author William Dalrymple. There was no brawl, other than one perceived insult over caste that was quickly forgiven. For five sunny days, people came together for a remarkable single purpose, to share ideas, listen and delve into the written word across national, religious and cultural borders.

International literary festivals are mushrooming around the globe. In imitation of Jaipur, which is now in its sixth year, 30 fairs have started throughout India alone. Other festivals have launched in Rangoon (last week saw the first Irrawaddy Literary Festival), Lahore (in late February 2013) and Dhaka. These new gatherings add to the well-established festivals in Edinburgh, Hay-on-Wye (Wales), Vancouver, Guadalajara, Jerusalem, Brisbane and various U.S. cities such as Washington, D.C., Miami and Los Angeles, just to name a few locales.

Perhaps the most unusual of the upstarts is the Palestine Festival of Literature, or PalFest, which mounted its fifth annual festival in 2012. Because checkpoints make it so difficult for residents to travel, the writers go out to the readers, each day speaking at a different site, not only taking their work to Palestinians but hearing locals’ stories in return. The brainchild of Egyptian-born novelist Ahdaf Soueif, PalFest is inherently political but says it pushes “the power of culture” over “the culture of power,” quoting Edward Said.

The Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) is overt about promoting international understanding. It fights against “the terrorism of the mind,” said the event producer, Sanjoy Roy, a friendly middle-aged guy sporting True Religion jeans and long gray-white locks. Novelist and co-director Namita Gokhale likes to describe the festival as a Mahakumbh of the mind, referring to the Kumbh Mela, the annual gathering of tens of millions of Hindus in one city to bathe in a sacred river. Gokhale said she aims to foster “understanding ourselves through literature, through words, through ideas, at a time when people are getting, at one level, more and more entrenched in their own set of prejudices.”Within this embracing vibe, JLF celebrates la difference. This year, while presenting a roster heavy with internationally acclaimed authors, the festival also included Indians who write in regional languages (17 were represented) and people marginalized in some way, such as women, tribal writers or those from oppressed castes.

“Damayanti Beshra, a woman writer in Santali, which is a tribal language, to me is as important as any major writer,” said Gokhale, who wants to “fight literary parochialism on all sides. All our Indian writers need to be exposed to more and more sounds and voices, and the international writers need to break out of their”—she paused, seeming to consider her words being spoken to me, the white American woman interviewing her — “slightly superior condescension to the literatures they haven’t been exposed to.”

About 60 authors born and living in the West (such as Ariel Dorfman, Sebastian Faulks, Zoe Heller, Peter Hessler, Howard Jacobson, Michael Sandel and Andrew Solomon) complemented a hundred writers who are nationals from India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and other Asian countries. Other presenters could be described best by the phrase “global soul,” the title of one of the panels. These were novelists such as Amit Chaudhuri (Indian now in East Anglia), Aminatta Forna (from Sierra Leone, now in London), Laleh Khadivi (Iranian Kurd now in San Francisco), and Manil Suri (Indian now in Baltimore) and a great variety of journalists, analysts, biographers and cultural critics, such as Mary Harper (Briton born in Kenya, now BBC Africa correspondent) and Faramerz Dabhoiwala (if you can guess the provenance of that name, you’re more a global soul than I am; he’s ethnically Parsi—from the Zoroastrian community in India—but grew up in England). Exceptionally complex masalas were Pico Iyer (British-born, ethnic Indian, American citizen living in Japan) and Abraham Verghese (ethnically Indian but from Ethiopia, now a doctor at Stanford).

Region was often the starting point for discussions with sessions on, for instance, Sunset on Empire, Writing the New Latin America and Out of Africa, the latter led by moderator, author and British Member of Parliament Kwasi Karteng, who all but accused fellow panelists who were not ethnically African as having no right to write about the place, which the audience and other panelists mostly disagreed with. And the politics on some panels were volatile: Consider such topics as Heaven on Earth: On Sharia Law and This House Proposes that Capitalism Has Lost its Way. Several panelists across JLF criticized American foreign policy, especially the use of drones — a topic carried into lunchtime discussions between delegates (attendees who paid for the special meals), authors and press.

But for the most part, the authors themselves pointed away from hot buttons toward the power of books to promote empathy. In a panel on The Novel of the Future, Pakistani novelist Nadeem Aslam, now living in London, said that while he has written about the war on terror and what’s happening in Pakistan, these are not the most important elements of his work. He cited Faulkner’s statement that the only subject worth writing about is “the human heart in conflict with itself.” The bottom line is “a man and a woman, and a man and a man, the meat and the membrane of life and death and everything else.”

He startled fellow panelist Zoe Heller, a Briton now living in New York, with an illustration: “For me to say I love Zoe, and for me to get blown up in an explosion, the real issue is that Zoe is now grieving.” For him as a novelist, the explosion is “the secondary thing…. This character and the grief; that is the interesting thing.” What a novel can do is to “build up a human being. Then you take him away to be tortured… and not only that, you create Person B who loves Person A, so when Person A (is) tortured, you don’t only feel my pain but you feel her pain. At some level, nonfiction can’t do this. This is why novels are important.”On panel after panel, writers returned to this theme of common human experience. If you had been a mosquito on the wall (there were more of those than flies), your takeaway would have been analogous, insect-wise, to the conclusion drawn by human attendees: There are lots of different colors of skin and varied features walking around, but inside us all is blood.

This idea was expressed directly by a man who famously never kills mosquitoes, the Dalai Lama, an author who was a big draw at JLF this year. “All people seek happiness and want to avoid suffering,” he emphasized, a statement he makes often. The crowd was exceptionally polite during his session, unlike the sharp-elbowed jostling for a packed presentation featuring cricket star Rahul Dravid.

Another major topic of discussion was the writer’s responsibility. In a panel titled The Writer and the State, Ian Buruma argued that fiction writers and poets, at least, don’t have a duty to take on the state, even a repressive one. Buruma referred to Mo Yan, the apolitical Chinese writer whose selection as 2013 Nobel laureate in literature has been criticized. He also cited Thomas Mann’s assertion that the writer should be above the state. For the writer and artist, Buruma said, “The true state of freedom is to choose the degree to which you want to be political.”

Selma Dabbagh, whose father is Palestinian and mother is British, lives daily with this challenge. Her first novel is set in Palestine. She described how for someone like her, with “education, the English language and the luxury of a foreign passport … your job is supposed to be to speak out, to communicate out,” but it’s “very difficult for a fiction writer to explore art” with that burden. Nevertheless, when moderator Timothy Garton Ash asked if she’d “like to be liberated from the duty of being the conscience of the nation, so you could just be a writer,” Dabbagh paused, then said no.

On that same panel, Argentine-Chilean author Ariel Dorfman discussed how the writer needs to “write from the tension, from the complication,” without a preconceived conclusion or agenda. “When you decide what the truth is going to be ahead of time, the result isn’t good literature. … If you knew what the truth was, you wouldn’t write. It’s that tension, that difficulty, that makes your fiction or nonfiction interesting. The worst writers are the ones who have the answers before they start writing.”

Later he added a statement that found much favor with attendees: He quoted Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal that “the constitutions of tomorrow will be constructed from the words from the love poems today.”

At The Literatures of 9/11 panel, I asked Reza Aslan and Homi Bhabha how they’ve observed writers daring to challenge the party line of their own societies, or not — considering how, for instance, Susan Sontag was vilified for her New Yorker piece shortly after 9/11. Aslan called critics “mindless” when they accuse writers of “giving voice to your enemies. … Susan Sontag was right on, which was ‘that that’s my job, that’s what I’m supposed to be doing, and if it makes you uncomfortable, then I’ve done my job correctly.'”Bhabha added, “One of the most important things in 9/11 novels is that the characters are deeply ambivalent and split. In Ian McEwan’s “Saturday,” he talks about his own ambivalence. In nationalist fiction, there’s either ‘love the nation, or hate the nation.’ The protagonists of 9/11 novels say that is too simplistic.”

In the Global Soul session, inveterate book festival-goer Pico Iyer noted, “Anything worth writing about is because we can’t get our minds around it.” To illuminate that point he cited relevant tidbits from Graham Greene, Leonard Cohen and Virginia Woolf. Throughout the festival, allusions were as thick as the tiny round shisha mirrors that traditionally decorate the colorful fabric collages for which Rajasthan is famous—here winking with flashes of meaning, light from the greater literary firmament.

Some of the authors brought startling world views. Writer Jamil Ahmad, who was posted in the 1970s with the Civil Service of Pakistan on the frontier and in tribal areas, then as a Pakistani minister in Kabul, spoke about his gorgeous, brutal novel, “The Wandering Falcon.” A questioner asked how the concept of honor, central to the novel, is used “to oppress women and people regarded as social inferiors.” Ahmad argued that honor as a form of law is just as valid as the legal systems of nation states, and tribalism “as a system has the least amount of tyranny built into it…. The tribal gene is imbedded in each of us, even today. Tribe is the basic building block of human civilization.” He bristled at the idea that bringing education, as defined in modern terms, to the tribes is a solution. “There’s a difference between literacy and education. Tribes may be more educated, though they might not be literate.”

At JLF, questions of tribalism and nationalism were topics as tangled as the stray electrical wires lying ready to trip people up in pathways and stairwells, a feature of many Indian venues, even ones as fancy-sounding as the Diggi Palace. Maybe it was wise for JLF organizers to start each of the five days with various musical sessions of Buddhist chants — mantras promoting compassion and world peace. Buddhist literature was a theme this year.

Of course there was controversy, though nothing compared to last year’s threats around participation by Salman Rushdie, who ended up staying away as a result. This year, furor arose over a satirical statement by progressive Indian cultural critic Ashis Nandy, who said that the “scheduled castes” (“untouchables” and other lower castes) and tribal groups now are more corrupt than the upper castes. In context, he was saying that corruption in these groups, now possible since they have a bit of power, is simply more apparent than that of the upper classes, whose machinations are well-hidden by their extensive networks.

The local police asked the festival organizers not to leave town because they had signed an agreement to “not hurt the sentiments of any community or religion during the literary festival.” The controversy was taken up at that same stage only a few hours later in a Freedom of Expression panel. Shoma Chaudhury, managing editor of Tehelka—an investigative news magazine in India—discussed the question with journalist John Paul Kampfner, Timothy Garton Ash (heading an Oxford project on global freedom of expression in the Internet age), Russia specialist Orlando Figes, and Kashmir and South Asia expert Basharat Peer. Later, Dalit writer Kancha Ilaiah, author of the controversial “Why I Am Not a Hindu” (his first novel, “Untouchable God,” was launched at the festival), came to Nandy’s defense. Whew.This hiccup was as bad as it got. A striking feature of this festival was its vibe of tolerance, of listening even when disagreements were vehement. The experience on the ground was friendliness. Perhaps that was a reflection of the personalities of the founders, who seemed to be having fun (voluble Dalyrymple did sneak a drink in the press area). Or maybe it was just the general spirit of India, where people are accustomed to stepping over potholes instead of complaining about them. The single festival bookstore, Full Circle, was well-stocked, tiny and always packed, but people didn’t whine as they had to squeeze past each other to get to each author’s section. They were focused on the books.

I’d heard that past Jaipur festivals had been chaotic, and though this one wasn’t, it was definitely loose. The first morning of the festival, signage and stores were still being arranged, but attendees just ignored the steel pipes and the workers lounging during tea breaks, their work unfinished. Security was lackadaisical; each day the ladies’ checkpoint operator swiped a wand over my purse but seemed to forget the backpack on my back, or vice versa. Though the festival was free, all attendees were required to register and wear badges, which were scanned inconsistently at the entrances (and, mysteriously, exits) of the six stage areas. There were no fire marshals; people crowded onto the grass when seating was full. Authors weren’t hustled off stage, and they were available to meet at lunch.

It’s gotten around writers’ circles that JLF is a great gig. Jaipur is the favorite festival of Alexandra Pringle, editor-in-chief at Bloomsbury Publishing in the U.K., because it has “the most diversity, the most beautiful city, and the best parties.” Iyer called Jaipur “the most festive festival. The last 35 years I’ve gone to festivals from Shanghai to Bogota, but I’ve never been to another one with elephants, candlelit maharajas’ palaces, vintage Rolls-Royces taking you to the parties at night, huge crowds on a Sunday afternoon, such engagement from the audience, such color, dawn-to-midnight schedules, and such a mix” of authors and genres.

Such extravagance may be why the Jaipur festival was in the red this year. Dalrymple said they plan to professionalize the festival next year, hiring a fundraiser, for instance, to expand existing corporate support. The festival, which started simply as a reading for 14 people in 2005 by Dalrymple and friends, has been a labor of love by the directors and Teamwork Productions, Sanjoy Roy’s company, which may end up subsidizing the festival this year because of overruns.

The next Jaipur Literature Festival is scheduled for Jan. 16-20, 2014. Authors who have signed on thus far from outside India include Alberto Manguel, Colm Toibin, David Grossman, David Mitchell, Ian McEwan, Jeanette Winterson, Jonathan Franzen, Jonathan Safran Foer, Malcolm Gladwell, Margaret Atwood, Michael Cunningham, Michel Houellebecq, Nicholson Baker, Umberto Eco and Yann Martell.

I hope the Jaipur Literature Festival keeps its vibe of love spiced with a bit of anarchy, the spirit of a Kumbh Mela. Here I’ve barely skimmed the surface of this five-day extravaganza, but maybe you get the gist. This festival has heart as much as brains. It’s a global passport that takes us beyond borders into an uber-land of the mind, our shared humanity, toward bhai bhai, brother brother.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.