A Mild Victory in Durban

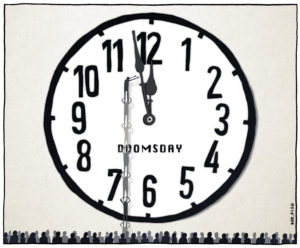

After the summit ended Sunday, initial reaction basically ranged from "Historic Breakthrough: The Planet Is Saved" to "Tragic Failure: The Planet Is Doomed."

I’m inclined to believe that the apparent result of the climate change summit in Durban, South Africa, might turn out to be a very big deal. Someday. Maybe.

That’s my view, but it’s hardly universal. After the meeting ended Sunday, initial reaction basically ranged from “Historic Breakthrough: The Planet Is Saved” to “Tragic Failure: The Planet Is Doomed.” Such radically different assessments came from officials and activists who have the same general view of climate change — that it’s real and something must be done about it — and who fully understand the agreement that the delegates in Durban reached.

The optimists and the pessimists disagree mostly on what they believe governments can do to curb the carbon and methane emissions that are warming the atmosphere, and when they are likely to do it. My conclusion is that for now, at least, the conceptual advance made in Durban is as good as it gets.

This advance is, potentially, huge: For the first time, officials of the nations that are the biggest carbon emitters — China, the United States and India — have agreed to negotiate legally binding restrictions.

Under the old Kyoto Protocol framework, which for now remains largely in effect, rapidly industrializing nations refused to be constricted by limits that would stunt their development. The United States declined to sign on to the Kyoto agreement or any other emissions-reduction treaty as long as China, India, Brazil and other rising economic giants got a free pass.

As a practical matter, this meant that while European nations worked to meet emissions targets — or, in some cases, pretended to do so — the most important sources of carbon were unconstrained. When Kyoto was adopted, China was well behind the United States as an emitter; now, it’s far ahead. India recently passed Russia to move into third place.

The Durban talks seemed likely to go nowhere until the Chinese delegate, Xie Zhenhua, announced that Beijing was willing to consider a legally binding framework for regulating emissions. With China now responsible for fully 23 percent of the world’s carbon emissions, this was an enormous step forward.

India, however, wasn’t so sure about agreeing to negotiate a “legal framework” specifying binding commitments. Delegates spent a ridiculous amount of time and effort refining that phrase, first moving to “protocol or legal instrument” and then falling back to “legal outcome.” European delegates pitched a fit, saying that “legal outcome” was so vague that it allowed the possibility of voluntary carbon limits rather than mandatory ones. The European Union threatened to scuttle the whole summit.

India’s environment minister pitched a counter-fit. “India will never be intimidated by threats,” Jayanthi Natarajan thundered.

Compromise language was found: By 2015, delegates will negotiate an “agreed outcome with legal force.” What does this mean? Within four years, there is supposed to be something like a treaty — covering developed and developing countries alike — that limits carbon emissions. This treaty or treaty-like document is supposed to take effect in 2020.

Those who see Durban as a bitter disappointment point out that smokestacks and automobile exhaust pipes continue to spew carbon, that atmospheric warming will continue apace, and that world leaders still haven’t actually done anything. The representatives in Durban agreed to negotiate a pact that wouldn’t take effect for nearly a decade — and that’s the best-case scenario.

But I think it may be enough. Durban’s real accomplishment was to keep the slow, torturous process of climate negotiations alive — with the biggest carbon emitters now much more fully involved. This buys time for real solutions to emerge.

In Shanghai recently I had dinner with Edwin Huang, marketing director for Suntech Power Holdings, a firm based in nearby Wuxi that is the largest producer of solar panels in the world. “We’re creating American jobs,” he told me: One of Suntech’s manufacturing plants is in Arizona.

China is getting serious about alternative energy. Emissions will continue to rise, but a commitment by China alone is enough to begin bending the curve. As companies such as Suntech — and, one hopes, U.S. competitors — keep bringing the cost of solar panels down, we can begin to get a handle on the problem. By 2020 or even 2015, carbon limits may seem less onerous.

But it’s necessary to keep the negotiating process alive until it is possible to reach a meaningful agreement. So yes, you can argue that the Durban conference only managed to kick the climate can down the road. For now, though, that might be enough.

Eugene Robinson’s e-mail address is eugenerobinson(at)washpost.com.

© 2011, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.