Part I: A Long Strange Loop

The emergence of veterans and active duty soldiers as the face of psychedelic research is the result of a controversial political strategy. Psychedelic soldiers. Generated by Russell Hausfeld using Midjourney.

This is Part I of the "The Ecstasy of Agony" Dig series

Psychedelic soldiers. Generated by Russell Hausfeld using Midjourney.

This is Part I of the "The Ecstasy of Agony" Dig series

This is the first of a multi-part Dig series, The Ecstasy of Agony, investigating the politics and ethics of psychedelic research and testing on soldiers. Subsequent pieces will be published over the next three months.

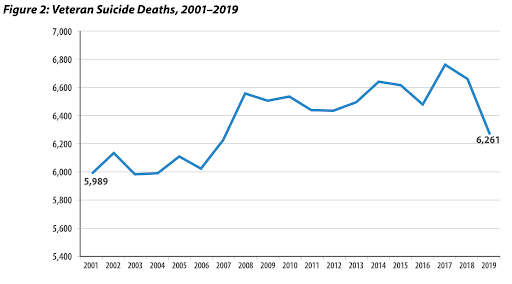

Last Veterans Day, former Texas Governor Rick Perry bounded onstage at a swanky affair in the ballroom of the Californian Hotel del Coronado. The audience of several hundred was not the crowd you might expect to pay $500 to hear a conservative politician. It was not made up of oil and gas industry professionals or would-be entrepreneurs seeking inspiration and business tips from the onetime presidential hopeful. The attendees were heavily represented by advocates for psychedelic therapy, gathered for an event called the “Strength in Numbers Gala to End Veteran Suicide.”

Our government, announced Perry, does “a great job recruiting young people into the military, teaching them how to break stuff, but doesn’t know how to transition them back into the private sector.” Therapies using psychedelic adjuncts, he continued, were the answer. “I’m willing to put my reputation on the line so that young men and women who have sacrificed for us have the opportunity to have these compounds available to them, because it saves lives.” He concluded saying he was “damn proud” to be fighting to save “American patriot lives.”

If Perry strikes you as an unlikely champion of psychedelic treatments, then you haven’t been watching much conservative media lately. In recent years, outlets from Breitbart to Fox News have become busy with conservative boosterism for treating veterans with molecules that less than a decade ago were the fringe domain of ravers, psychonauts and a few coastal in-the-know therapists. Perry was himself introduced to the concept by Marcus Luttrell, a former Navy SEAL turned host on Glenn Beck’s conservative network TheBlaze.

The conservative media excitement around psychedelics has also infected Republican lawmakers. This past July, Florida Republican firebrand Rep. Matt Gaetz teamed up with Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York to file an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) encouraging government research into the therapeutic potential of MDMA and psilocybin for military service members. During his testimony before the House Rules Committee, Gaetz was joined by former Navy SEAL Republican Rep. Dan Crenshaw of Texas.

The proposed amendment arrived shortly after the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) began psychedelic trials in its facilities for the first time since the early 1960s, when military-run experiments inadvertently aided the birth of a national counterculture by dosing many future icons of the decade’s psychedelic scene. Merry Prankster Ken Kesey, who famously drove a bus of hippies around the U.S. conducting “Acid Tests,” was first given LSD at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Menlo Park.

When the government conducted these Cold War experiments on soldiers and unwitting walk-ins like Kesey, they were not thinking about healing trauma. Far from it. The Pentagon and the CIA were focused on using psychedelics — especially LSD — as tools for mind control, torture and brainwashing. When researchers failed to establish psychedelics’ utility as strategic weapons, followed by the drugs embrace by Hippies, the anti-war movement and the broader youth culture, the government cracked down on the molecules and those who used them.1

When the Nixon administration criminalized psychedelics in 1968, bringing dozens of clinical trials to a screeching halt, the wider psychedelic subculture continued to flourish. It was defined by a zeitgeist of artistic expression and anti-war, pro-labor and environmentalist politics. As the “war on drugs” deepened into the ’70s and ’80s, the Pentagon that helped introduce psychedelics into society represented the authoritarian antipode of psychedelic culture. For good reason, military and law enforcement bodies were different faces of the same archetypal enemy of the criminalized scene.

In light of this history, the starring role played by veterans and right-wing politicians in the current “psychedelic renaissance” represents the closing of a long, strange circle: the people and institutions most responsible for enforcing the criminalization of psychedelics are now lauded and prized as ideal treatment demographics.

This is an odd development, but not an accidental one. The adoption of psychedelic treatments by the military — first to treat veterans, and to potentially augment the fighting capacity of active-duty personnel in the future — is the outcome of a concerted, long-term strategy begun by a small group of researchers and advocates looking to mainstream psychedelic pharmaceuticals in the depths of a psychedelic Dark Age. Beginning in the early 1980s, they started conceiving a strategy of finding trial groups that were most culturally acceptable, and publicly sympathetic, to an America leaning further right by the day. They hypothesized that focusing on cohorts for whom the general public felt a nationalistic sense of responsibility would accelerate acceptance of psychedelic treatments and start money flowing into the coffers of advocacy groups and research efforts.

Forty years later, the strategy has largely been vindicated. But any celebration over advances in the mainstreaming of psychedelic therapy should be tempered by a recognition that it has arrived with a cost to the values and vision of the psychedelic community and its original pioneers.

* * *

In 1976, the legendary psychedelic chemist Sasha Shulgin rediscovered a molecule called MDMA in his laboratory shack on a hilltop in Lafayette, California above the San Francisco Bay.2 He initially called it “window,” because he saw the drug as being able to strip away users’ habits and offer a clearer perception of the world. Psychotherapist Leo Zeff was so impressed by the MDMA samples he received from Shulgin in 1977, he traveled throughout the U.S. and Europe sharing the drug with thousands of therapists and teaching them how to use it in their practices. Zeff called the drug “Adam,” reflecting his belief that the drug induced a state of “primordial innocence.” MDMA effects such as a reduction of fear and increased levels of communication were central to the drug’s therapeutic benefits. Practitioners found success using MDMA for marriage counseling, sexual trauma processing, depression and more. Many early reports noted that the role of the therapist was greatly reduced: patients largely benefitted from moments of self-discovery using the drug.

The key factor in the use of MDMA to treat post-traumatic stress disorder is the drug’s effectiveness in reducing fear response. This is because PTSD makes it hard, if not impossible, to recall and assess traumatic memories without an intense and inhibiting fear response. Some clinical literature suggests MDMA allows users to review and assess their traumatic memories with clarity — and without triggering an intense fear response. The hope of psychedelic advocates is that the impact of this treatment carries beyond the therapist’s office, and patients can deal with their post-traumatic stress in healthier ways.

PTSD is a relatively new diagnosis — it was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980 — but comparable conditions have been documented in soldiers for centuries. The observation that war not only destroys bodies but also minds was made by the ancient Romans, who noticed soldiers suffered what they called “battle fatigue.” Other names for war-related PTSD throughout history have included “war neurosis,” “warrior’s heart,” and “shell shock” — all referring to post-conflict maladaptations due to war trauma. Effective treatment for this condition has been hard to come by. Even today, the FDA-approved medications for PTSD — sertraline (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil) — have a roughly 20% to 30% success rate in achieving complete remission of PTSD symptoms.

Comparatively, one MDMA trial studying 24 veterans with PTSD claims 68% of participants experienced significant remission of symptoms one month after treatment. “There are also still some challenges I have to face from time to time related to the PTSD,” one participant from that study explained. “But now I am able to work through them without getting stuck.”

It’s hard to argue with helping people who need it, but veterans are only one cohort suffering from PTSD. And for most of the pioneering psychonauts and psychedelic thinkers of the last century, it was far from a priority group. This began to change when a young psychedelics aficionado and advocate named Rick Doblin stepped out of rank with a plan of his own.

* * *

In 1976, the year Sasha Shulgin synthesized MDMA, 23-year-old Rick Doblin was running a construction company in Florida, dodging a felony for resisting the Vietnam War draft, and experimenting with copious amounts of psychedelic drugs like LSD and magic mushrooms. In the early 1980’s, Doblin discovered MDMA and soon became a champion of the drug, joining the effort to introduce the molecule to therapists. When the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) made moves to reschedule MDMA in 1984, Doblin — along with therapists Alise Agar and Deborah Harlow — founded an organization called Earth Metabolic Design Laboratories (EMDL). EMDL conducted early MDMA toxicity studies in animals and coordinated responses to the DEA’s rescheduling of MDMA to Schedule 1, which would assign harsh penalties to the at-that-time legal drug.

When EMDL failed to convince the DEA not to reschedule MDMA in 1985, a fault line emerged between Doblin and his colleagues within the organization, some of whom blamed Doblin’s proselytizing media tactics for the rescheduling.

“Rick…may be single handedly responsible for the emergency scheduling of MDMA by the government,” a source from EMDL told New York in 1985. “If there’s any more media coverage, we stand a good chance of losing this thing, which would be a shame because a lot of people have invested years of work on MDMA.”

Doblin acknowledged a difference of opinion on communications strategy, but defended the approach that would foreshadow his career-long affair with the media. “I think if people are going to do stories, they might as well have the right information,” Doblin told New York in the same article. “I might have to start my own foundation.”

That he did. In 1986, Doblin founded the non-profit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) with the mission to mainstream psychedelic pharmaceuticals by putting them through FDA-approved clinical trials.

As David Nickles and Lily Kay Ross of the psychedelic industry watchdog Psymposia reported earlier this year, Doblin has been operating under the belief that MDMA was a “safe and effective adjunct to psychotherapy” well before there was documented clinical evidence for it.3 He just needed public opinion to catch up to his own. The choice for MAPS to take MDMA through clinical trials hinged on Doblin’s belief that it was a relatively mild psychedelic that didn’t frighten the general public. The molecule was less burdened with cultural preconceptions than classical psychedelics such as LSD or mushrooms, he believed, and an obvious first step toward wider acceptance.

Since the inaugural 1988 edition of the MAPS Bulletin — a running chronicle of the organization’s research, financial reports and public relations — Doblin has stated his intentions to change public perceptions about psychedelic drugs by working with the government. In 1988, when announcing his enrollment in a master’s degree program at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, Doblin cheekily wrote, “They say, ‘if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em’ and we all know how often They are right.”

In his book, Acid Test: LSD, Ecstasy, and the Power to Heal, Tom Schroder wrote that Doblin didn’t necessarily want a government career, but “he did want to know how to manipulate the levers and pulleys that could move public policy on the issue of psychedelic medicine.” Doblin interviewed with the CIA at one point while at Harvard, but declined a position when asked if he was interested in creating psychological profiles of world leaders. He stuck with his work at MAPS instead.

In MAPS’ early years, organizational messaging focused on using psychedelics to treat populations like survivors of sexual assault, cancer patients and drug addicts. Veterans and military service members were largely absent from the public messaging. That changed in 1994, when MAPS secured FDA approval to conduct a Phase 1 safety trial with MDMA in human subjects, and also announced a partnership with Dr. Manuel Madriz Marin, the chief psychiatrist at the Military Hospital in Managua, Nicaragua, to study the effectiveness of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in the treatment of “soldiers and civilians traumatized during the Nicaraguan Civil War.”

Although the trials in Nicaragua were canceled in 1996, Doblin found partners in Israel to take on the task of studying MDMA treatment for war-related PTSD. By 1998, MAPS had pledged $50,000 to Dr. Moshe Kotler at the University of Ben-Gurion to design and conduct research into MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for PTSD. The initial language describing this research seemed careful not to specify veterans or military personnel, stating the focus was “war survivors and car accident” victims. But the inclusion of soldiers was clearly implied by this language, as well as Kotler’s history as the former chief psychiatrist for the Israeli Defense Forces.

The same year MAPS’ sponsored Kotler, Doblin defined a shift in MAPS’ media strategy. Moving forward, the organization would seek to illustrate the benefits of psychedelics to “even the most conservative members of our society.” In addition to presenting research data, MAPS’ Bulletin would henceforth print compelling anecdotal accounts of psychedelic use.

As Doblin tells it, this decision was the result of a chance conversation with ex-Boston Mayor Ray Flynn and his wife about medical marijuana. Doblin told Flynn about his own research at the Harvard Kennedy School, which involved medical marijuana, but did not feel like Flynn was entirely convinced of its usefulness. During the conversation, a bystander chimed in to say that his wife — who had died of cancer — found that the only thing that helped her chemotherapy-related nausea was Marinol, a legally available THC pill.

“Mayor Flynn then told us that emotional stories like [that] provided the political cover people in office would need to advocate a policy shift,” Dobin later wrote.

Over the next few years, Bulletin editions included personal accounts from writers who used MDMA to deal with a partner’s cancer diagnosis, get over an eating disorder, soothe sexual trauma and more. MAPS was trying out the Flynn strategy, and with some success. But the organization had yet to develop a narrative for MDMA that fully caught fire with the public.

* * *

In the early aughts, the odds seemed to worsen for Doblin’s MDMA crusade.

In 2001, the U.S. Senate made the decision to increase penalties for MDMA, essentially putting punishment of its possession on par with heroin. Senators heard testimony that included a number of presumed harms of MDMA — including a disproven claim that MDMA causes “holes in the brain” — and refused to acknowledge the existence of any possible benefits associated with the drug.

Due to misinformation and public stigma, MAPS struggled to kickstart its PTSD trials. The Medical University of South Carolina, where MAPS had planned to conduct trials, backed out at the last minute. And the independent Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB) approved MAPS’ protocol only to revoke its approval months later on the basis of “conversations…that a WIRB staff person had sought with some outside researchers.”

“How can MAPS move forward with MDMA psychotherapy research in this overheated environment?” Doblin wrote.

His solution was to double down in his appeals to the FDA. In an essay in the Bulletin, Doblin described the FDA as “more responsive to the needs of seriously ill patients than to the misguided crusade for a drug-free America” and a natural “safe harbor” for a pilot study of MDMA in the treatment of patients with chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Winning over the FDA was paramount to MAPS’ ongoing efforts in the U.S. as well as abroad. The same year the Senate increased MDMA penalties, Doblin learned that MAPS’ research with Kotler in Israel would only receive regulatory approval “after the FDA had approved an MDMA/PTSD protocol, but not before.” On November 2, 2001, the FDA approved MAPS’ protocol for treating PTSD with MDMA, allowing planning to begin on Phase 2 trials. Two years later, in September of 2003, MAPS received approval from an IRB, began the process of obtaining a DEA Schedule 1 license, and announced plans to begin recruiting for Phase 2 trials in 2004.

Things were back on track.

While getting all of this underway, Doblin articulated the importance of finding a suitable patient population. There was a need, he wrote, to identify a patient cohort for whom other interventions had little success. The “patient population should also be a group that the general public feels compassion towards, in order to help overcome resistance to the idea of the therapeutic use of psychedelics,” he wrote in October 2002.

In 2005, MAPS formally changed its U.S. protocol to include people “with war-related PTSD of five years or less duration, such as Iraq and Afghanistan veterans.” 4

News of this calculated decision was greeted with criticism and controversy, in the U.S. and abroad.

“The United States government has found a new way of recruiting soldiers for the Iraq War: It’s offering them ecstasy,” a correspondent for the German news magazine, Der Spiegel, wrote in February of that year. “The trick is, the soldiers only get the free drugs after they have seen enough fighting to be experiencing flashbacks, recurring nightmares and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.”

“In other news,” he noted wryly, “the U.S. government spends $20 billion a year on the drug war.”

Criticism within the MAPS’ community wasn’t so cloaked in irony. In the Summer of 2005, the MAPS Bulletin published a range of comments from a heated debate on its email forum. While some believed that soldiers deserve mental healing, many in the community expressed fury and revulsion at the prioritization of soldiers over other demographics.

“Should we pursue the consequentialist road of allowing MDMA to be used as a war weapon so that in the future it is widely available for general therapy?” One user asked. “Or should we draw a line on what is a moral use of the substance right now? I feel disgusted by the prospect of healing MURDERERS [sic] instead of preventing the murder with MDMA.”

Doblin responded to such criticism by kicking the can. Determining whether military funding and excitement for MDMA research “would be a misuse of a precious tool or an important step toward ‘mainstreaming’ MDMA” was “an issue that is years down the road,” he wrote.

Despite moving forward with its plan in the face of community discomfort, MAPS mostly failed in its attempts to recruit veterans into MDMA trials until winter of 2007. At this time, the organization requested approval from FDA to include a veteran who did not meet the “treatment-resistant” category that was required to participate in MDMA trials.

“We believe that it would be worthwhile to study this individual in order to provide more experience working with veterans in this Phase 2 study, before we go on to designing a larger, Phase 3 trial that will include veterans,” Doblin wrote.

He has since noted other strategic reasons for including veterans in clinical trials.

“Most of the people that have PTSD are women who’ve been sexually abused or raped or domestic violence, and they’re sympathetic,” Doblin told Marianne Williamson on her podcast. But, he said, these groups were not quite as sympathetic as veterans to the general public. Doblin later elaborated to David Nickles and Lily Kay Ross that, “interpersonal violence and trauma are uncomfortable subjects for many people, whereas combat-related trauma is widely recognized as a national responsibility to address.”

* * *

In 2009, MAPS began planning its first veterans-only trial. One stated reason for the trial, held in Charleston, South Carolina, was the need to discover if veterans with battle-related PTSD responded to treatment differently than individuals with other causes of PTSD.

The results from the first MAPS pilot study were published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology in 2010. The data — based on reports from a mixed PTSD population that included two veterans — showed a lack of reported adverse events and a greater decrease in PTSD scores among individuals who received MDMA than those who received placebo. A media tsunami followed: more than 140 publications and networks covered the paper, including a positive write-up at Military.com.

In an article, Doblin described the hype as “signs of our growing mainstream acceptance” and believed that “MAPS’ so far fruitless efforts to collaborate…with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense and the National Institute on Mental Health no longer seem so far-fetched.”

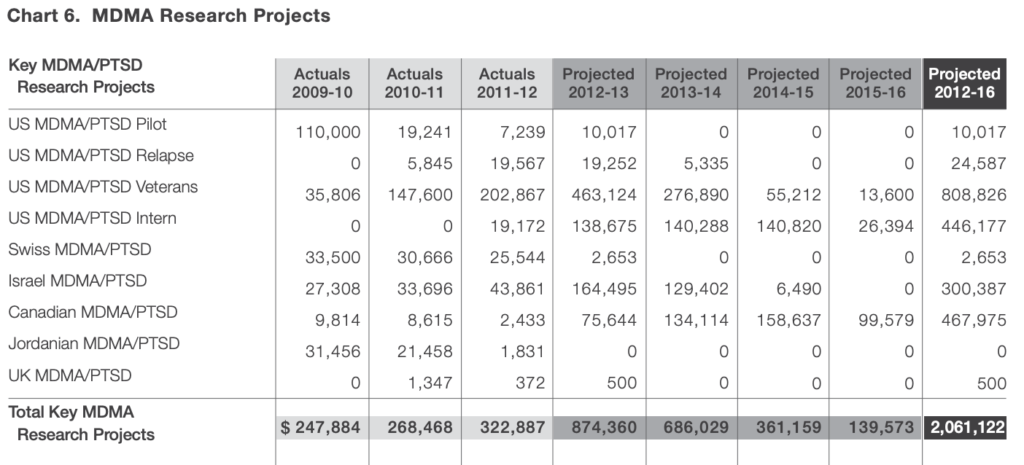

Over the next two years, MAPS increased the number of veterans to be enrolled in its veteran-exclusive trial from eight to 24 (more than the original number enrolled in the general pilot study), and opened up recruitment to police officers and firefighters. In financial reports and research updates, Doblin repeatedly stressed that he hoped investigating PTSD treatment in U.S. veterans would lead to funding opportunities from a broader group of donors and government agencies. In a 2012 financial report, MAPS anticipated spending double the funds on veteran-focused PTSD projects between 2012 and 2016 than any other PTSD treatment projects.

Doblin’s hopes for broader funding and collaboration were realized in 2013. MAPS began discussions with the VA regarding a possible collaborative study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with war-related trauma, and launched an Indiegogo fundraiser specific to veterans that doubled MAPS’ previous crowdfunding records. The Libra Foundation made a large donation to MAPS with $40,000 earmarked for veteran research.

At the end of 2014, veterans were a major focus of MAPS’ work. No longer were they only implied as potential recipients of MDMA in trials for “war survivors.” MAPS was now announcing its 20th subject in a veteran-exclusive trial and calling treatment of veteran PTSD the “foremost” opportunity on the horizon for the organization. Preparation had also officially begun for a series of Phase 2 studies in collaboration with researchers from the VA, using MDMA along with other traditional methods for treating veteran PTSD.

Meanwhile, veteran psychedelic activists scratched their heads and reiterated concerns about MAPS’ centering of military needs. Psychedelic cultural commentator Erik Davis spoke for many disaffected MAPS supporters when he commented critically on the organizations’ pivot towards military PTSD, reminding the nonprofit that it had been financially supported, not by the Pentagon for over two decades, but by a criminalized subculture with very different values.

“Successfully treating anyone’s PTSD is a laudable goal,” Davis wrote in Erowid Extracts in 2013. “But the sentimentality and heroic triumphalism that MAPS taps in order to publicize this research (funded by 25 years of contributions from psychedelic culture freaks) glosses over the disturbing possibility that MDMA therapy could one day be used with active-duty soldiers, a deployment that turns the compound into affective grease for the military machine.”

That disturbing possibility was closer to reality than Davis seemed to realize. In fact, Doblin had floated the idea of treating active-duty soldiers with MDMA as early as 2012.

* * *

Behind the scenes, a number of notable players contributed to MAPS’ connections with government agencies like the VA and DoD throughout the 2000s. One key figure was Richard Rockefeller, great-grandson of Standard Oil co-founder John D. Rockefeller. Following the scion’s untimely death in 2014, Doblin published a memorial that noted he “was the person most responsible for moving the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Veterans Administration (VA) [sic] from resistance to collaboration in the effort to explore MDMA’s potential as an adjunct to psychotherapy for PTSD.” Doblin also disclosed that he and Rockefeller had exchanged 2,379 emails and that “his passion for exploring the potential of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to heal PTSD matched my own.”

Rockefeller died in a plane crash in 2014, but publicly discussed the merits of MDMA treatment months before at the San Francisco Commonwealth Club. At one point in this discussion, he stressed that the VA and the DoD have moral and economic incentives to seek better PTSD treatments and ways to increase resilience in active-duty soldiers.

In 2014, a retired U.S. Army sergeant named Tony Macie — the first veteran treated in MAPS’ clinical trials — began lobbying in Washington D.C. on behalf of MAPS research. He wrote that he met with Republicans and VA officials and shared impactful anecdotal reports with them (the tactic Doblin had been stressing since the ’90s). “Having veterans speak about their experience directly was a huge shift,” says former MAPS Director of Strategic Communications, Brad Burge. “Tony Macie was one of the first.”

Other veterans also began to speak more freely about their experiences with psychedelics around this time. In 2013, a Marine veteran named Ryan LeCompte began operating a nonprofit organization called Veterans for Entheogenic Therapy (VET) with the mission to provide veterans with psychedelic healing. This organization sponsored travel for veterans seeking legal psychedelic treatment at a time when MAPS reported it received 900 applicants for a 24-person veteran-exclusive trial. MAPS later became a fiscal sponsor of a study headed by LeCompte investigating the safety and effectiveness of treating veterans with ayahuasca, a psychedelic brew traditionally used by a number of South American Indigenous communities.

2016 was a milestone year for MAPS and its veterans-first strategy. On October 18,MAPS submitted its FDA End of Phase 2 packet for its general MDMA/PTSD trials. Nine days later, research officially concluded on its first veteran-exclusive trial. In anticipation of Phase 3 trials, MAPS successfully applied for “breakthrough therapy” designation — which guaranteed that the FDA would work with MAPS to complete trials as efficiently as possible. MAPS also provided treatments to the first two recruits in its MDMA/PTSD collaboration with VA researchers.

The following year, MAPS was granted FDA approval for Phase 3 MDMA/PTSD studies, just as the short-term results of its first veteran-exclusive Phase 2 trial were published in “The Lancet Psychiatry.” MAPS reported that 68% of veterans who received therapy and two full doses of MDMA no longer qualified for PTSD a month after treatment.5 These results bolstered the launch of new organizations such as the veteran-led group, Heroic Hearts Project (HHP). Like LeCompte’s VET organization, HHP provides support for veterans to receive legal psychedelic treatment.

With the publication of these results, and MAPS’ Phase 3 trials looming on the horizon, a new era of psychedelic science was beginning. Never before had a psychedelic treatment made it this far through clinical trials. Data in hand, the stage was now set for MAPS to begin mainstreaming psychedelics to skeptical parties like conservative media figures and politicians.

* * *

In 2018, MAPS made a number of overt — and, within many psychedelic-using communities, highly controversial — plays to court right-wing influencers and politicians.

The main figure in this effort was a retired U.S. Army sergeant and former MAPS clinical trial participant named Jonathan Lubecky. In March, MAPS hired Lubecky to act as the nonprofit’s first Veterans and Governmental Affairs Liaison — he self-identified as MAPS’ “conservative whisperer” — formalizing his role of spreading the word about MDMA among his network.

In February, Lubecky appeared on stage at the 2018 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) to promote the therapeutic benefits of MDMA for veterans, followed by a conservative media blitz. He appeared on Breitbart Radio to discuss ending the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) monopoly on marijuana research (a cause MAPS had been working towards for decades), and spoke with programmers from SiriusXM’s Patriot Radio. Lubecky also claims to have discussed MAPS’ research with Sean Hannity, Andrew Wilkow, Nigel Farage and American Conservative Union chairman Matt Schlapp. Lubecky has held meetings with and lobbied a bevy of other influential figures on the right, including Donald Trump, Mike Pence, Steve Bannon, Rudy Giuliani and Alex Jones. This is what MAPS hired him to do, and he has done it with gusto.

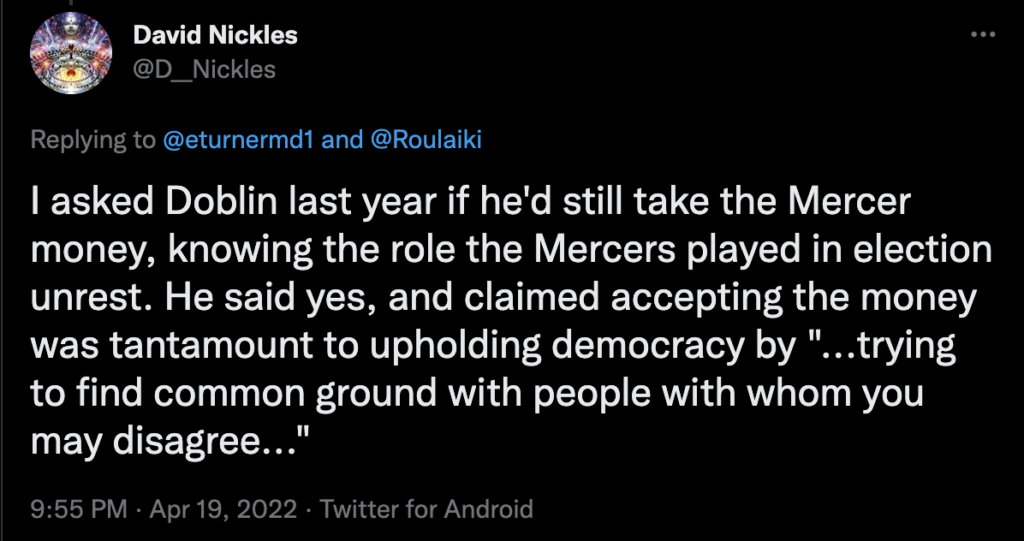

Lubecky wasn’t the only conservative operator supporting MAPS’ work. The year of Lubecky’s CPAC appearance, MAPS accepted a $1 million donation from conservative mega-donor Rebekah Mercer to help complete funding for Phase 3 clinical trials (these funds were, however, restricted to veteran treatment). “With this gift,” Doblin said at the time, “the Mercers are on the forefront of scientifically rigorous medical innovation. We’re inspired and deeply grateful for their commitment [and they] are to be commended for their gift.”

The announcement of the gift and Doblin’s response further alienated advocates opposed to MAPS’ strategy. They noted that the Mercers were known for their involvement in funding anti-abortion efforts and climate change denial, among other right-wing causes. More recently, the Mercers are accused of providing funding to “numerous key players who helped foment the January 6 insurrection” and bankrolling the conservative social media platform, Parler.6

“I have problems with MAPS accepting the Mercer donation because of the legitimacy this lends people who support — with multimillion dollar donations — right-wing, racist, antiSemitic, anti-democratic and anti-environmental movements,” the psychedelic researcher Scott Hill commented on MAPS’ Facebook page. “[MAPS is] in effect giving credibility to people who support the most insidious tendencies in our culture.”

MAPS largely ignored such voices and deepened its collaboration with military agencies. In 2019, it announced three trials in partnership with VA-affiliated researchers. In 2021, MAPS’ Bulletin introduced a new comms agenda that for many exemplified the problems with Doblin’s military-first strategy. The Bulletin article, “Moral Injury and the Promise of MDMA-Assisted Therapy for PTSD,” called for using MDMA to treat the condition of “moral injury” among soldiers — including “injuries” suffered through committing acts of violence against innocent people and possibly committing war crimes.

To illustrate this, the article describes a hypothetical veteran “haunted by the many times he stormed into people’s homes at night, turning the house upside down looking for weapons, taking fathers away from crying families to military prisons.”

Moral injury, the article notes, is different from PTSD in that it typically involves an individual involved or complicit in the perpetration of an act with which they morally disagree. MDMA is proposed as a promising treatment for morally injured soldiers looking to achieve self-forgiveness for potential war crimes. Whether they would be any more or less likely to get back in the field and do it again is not addressed.

This is exactly what Erik Davis and others had been warning about for years. MAPS had effectively turned psychedelics into “grease for the military machine,” and was funding the transformation with money provided by right-wing oligarchs.

* * *

The conservative-military embrace of psychedelics spearheaded by Doblin really began to accelerate in the 2010s alongside another dramatic development concerning to many psychedelic advocates: A spike in traditional pharma interest and a rise in so-called “corporadelic” tactics like rent-seeking from molecules once associated with spiritual and anti-capitalist values. In 2022, nearly 50 publicly listed companies exist in an expanding psychedelic pharmaceutical landscape; financial sites report that the global market could be worth $8.31 billion by 2028. Due to its political reach and advanced-stage clinical trials, MAPS remains the backbone of this industry, though it is likely to be outpaced by for-profit companies with greater funding in the near future.

MAPS is sure to live on, however, in the DNA of these psychedelic startups, many of which have followed MAPS’ lead and incorporated treatment of military service members into pilot projects, outreach efforts and advertising.

This can be seen in the case of Atai Life Sciences, a German psychedelic pharma incubator that has paid $50,000 to be listed as a “Diamond Sponsor” of the upcoming 2022 “Gala to End Veteran Suicide” (where Doblin and Perry will be returning speakers). The event organizer, VETS, has received millions in donations to send veterans to legal psychedelic retreats outside the country. Field Trip, a psychedelic startup developing pharmaceuticals and physical clinics, introduced a program called “Field Trip Basecamp” in 2020 with the specific goal of providing psychedelic treatment to military veterans. The initiative’s tagline — “Return, Reset, and Relaunch” — is a winking play on the most famous psychedelic slogan of another era.

The new crop of veterans-focused psychedelic initiatives includes efforts by Revitalist and Wake Network, Inc., which have partnered to offer ketamine infusions and psilocybin to military service members and veterans. Together, these companies created the “UNIT retreat”, which sends participants to the Veterans Healing Farm in North Carolina, followed by a five-day psilocybin retreat in Jamaica (packages range from $4,200 to $5,600.) The Amsterdam-based Psychedelic Warriors, meanwhile, charges €1,495 for single-sessions targeted to veterans, police, firemen and “active special forces operators.”

While there is an unquestionable need for new approaches to PTSD treatment and suicide prevention among veterans, the strategy pursued by MAPS required a break with much of the community that supported it for decades. To its critics, MAPS has betrayed the legacy by prioritizing military veterans and downshifting groups that had been highlighted when psychedelic research restarted in the ’80s and ’90s, such as sexual assault victims, cancer patients and drug addicts. The acceptance of military servicemembers and veterans as the treatment population du jour within the “psychedelic renaissance” can be seen as completing a winding chapter in psychedelic history. Initially embraced as tools for waging and winning the Cold War, psychedelic drugs have returned home to, of all places, the Pentagon, heralded as salves for the perpetrators and victims of war.

Endnotes

[1] The government itself did not halt research until 1973, when CIA Director Richard Helms ordered all files on Project MKUltra—the agency’s research into LSD, brainwashing, and more—to be destroyed.

[2] MDMA was initially discovered by Merck Pharmaceuticals in 1912, and tested as a chemical warfare agent on animals in 1953 by the U.S. government.

[3] Full disclosure: Nickles and Kay Ross are colleagues of mine at the non-profit psychedelic industry watchdog, Psymposia.

[4] TruthDig contacted MAPS and Rick Doblin to find out why veterans were initially excluded from MDMA clinical trials. MAPS Director of Communications Betty Aldworth did not know veterans were ever excluded. When provided documentation that veterans were initially excluded, Aldworth did not respond. Doblin did not respond either.

[5] It should be noted that most psychedelic trials have only been conducted with small pools of participants and have been critiqued for methodological issues like non-standardized treatment plans and an inability to truly create a double-blind experience. Ethical concerns around therapist touch and accountability are also factors of concern after multiple reports of abuse in underground and aboveground psychedelic networks have surfaced—including at VA locations.

[6] In an email correspondence with Psymposia Managing Editor David Nickles after January 6, 2021, Doblin wrote that — even knowing what he now knows about the Mercers — he would still accept their money.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.