A God in Ruins

A new novel takes its place in the line of powerful works about young men and war, and recognizes the courage of those in war's aftermath, who are left to pick up the pieces.

Little, Brown and Company

|

To see long excerpts from “A God in Ruins” at Google Books, click here. |

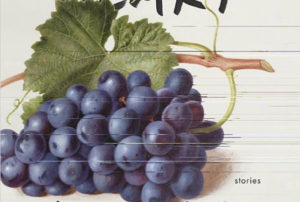

“A God in Ruins”

A book by Kate Atkinson

At the end of her magnificent new novel, “A God in Ruins,” Kate Atkinson appends an author’s note, in which she declares, “I think that all novels are not only fiction but they are about fiction too.” True enough and not exactly breaking news for those of us readers who’ve lived through the past half-century of postmodern fiction. But Atkinson states what has (by now) become the obvious in order to make a riskier, less intellectual admission: “I think that you can only be so mulishly fictive if you genuinely care about what you are writing.”

There you have it: The element of compassion that distinguishes Atkinson from those practitioners of metafiction who nudge readers in the ribs, chiefly, it seems, to remind us of their own cleverness and our own readerly gullibility.

For Atkinson, however, self-referentiality is never a mere party trick but a means to arrive at a more profound end. In “Life After Life,” her best-selling 2013 novel, she tells the story of Ursula Todd, an Englishwoman born in 1910 who dies repeatedly (murder, suicide, influenza, the London Blitz, an accident) and is repeatedly reborn. Ursula’s rebootings bring home the contingencies of life, the relative powerlessness we all share in the face of larger forces, like war.

Atkinson calls “A God in Ruins” a “companion” to “Life After Life.” That’s because this novel spotlights Ursula’s younger brother, Teddy, and particularly focuses on his service as a Royal Air Force bomber pilot during World War II. Of all the many fragmented stories Atkinson tells here, of all the many big questions about courage, responsibility and cosmic luck she self-consciously mulls over, one thing stands out: In “A God in Ruins,” she’s written not only a companion to her earlier book, but a novel that takes its place in the line of powerful works about young men and war, stretching from Stephen Crane’s “Red Badge of Courage” to Kevin Powers’ “The Yellow Birds” and Ben Fountain’s “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk.”

In stop-and-start fashion, “A God in Ruins” hops around in narrative perspective and era, from Teddy’s golden between-the-wars childhood to his grim fade out as a nonagenarian. Atkinson’s nonlinear story line enhances the poignancy of time passing: For instance, during the Blitz, a young Teddy on leave recklessly spends his money on drinks and a hotel room because, after all, there are “no pockets in shrouds”; a couple of pages on, his grandson complains that “Granddad’s got so much crap” as Teddy is being packed off to an assisted-living residence with most of his possessions destined to be “offloaded on charity shops.” Similarly, in the blink of an eye, the goldfish that Teddy, as a young father, wins at an agricultural fair for his daughter is “echoed” in Teddy’s membership in the so-called “Goldfish Club” of bomber pilots who ditched their planes into the sea, as well as in his diagnosis of himself as a goldfish in captivity once he’s ensconced in his old-age home. Atkinson elegantly executes these chronological loop-de-loops, leaving a reader to marvel at that most banal of epiphanies: How fast life goes by.

That is, how fast it goes by if one is fortunate enough to enjoy a normal life span; most of those RAF crewmen were not. Atkinson reminds us that “the average age of these men (boys, really), all volunteers, was twenty-two … fewer than half of them survived.” Drawing on firsthand accounts of those airmen’s experiences, Atkinson brings Teddy and his crew into the thick of things. Here are some snippets from an extended description of their passage through a titanic thunderstorm:

“The turbulence was atrocious, rocking ‘J-Jig’ around as if it were a toy aircraft. As flies to wanton boys.“They were flying on two engines, fighting a headwind, still icing up, with no wireless and only dead reckoning to get them home.

“Teddy was considering giving the order to abandon the aircraft when something even more alarming happened. Mac started singing. Mac! And not some ditty from the Canadian backwoods but a cacophonous performance of ‘Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.’

“It transpired that his oxygen tube had become frozen.”

“A God in Ruins” contains many such harrowing scenes, rendered in economical detail and occasional black humor. Atkinson’s skills as a suspense writer serve her well here: It’s not till the final pages of the novel that we learn who makes it through the war and who doesn’t. As powerfully as it conveys life-and-death struggles in the air, “A God in Ruins” also compels readers to recognize the courage of those in the war’s aftermath, who were left to quietly pick up the pieces.

Maureen Corrigan, who is the book critic for the NPR program “Fresh Air,” teaches literature at Georgetown University.

©2015, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.