|

To see long excerpts from “Making Make-Believe Real” at Google Books, click here.

|

Garry Wills, emeritus professor of history at Northwestern University and Pulitzer Prize winner for “Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America,” is, in addition to being a historian and journalist, a lover and scholar of Shakespeare. “Making Make-Believe Real: Politics as Theater in Shakespeare’s Time” is his 46th book, and his fourth that deals with some aspect of Shakespeare and the Elizabethan era.

“Making Make-Believe Real” casts a new light on Shakespeare’s characters of Mark Antony, Cleopatra, Richard III, Othello, Henry V, Petruchio and Kate, and others in a study of political stagecraft during the reign of Elizabeth I, a time of political and cultural change when “the power of make-believe to make power real was not just a theory but an essential truth.”

He spoke to us from his office at Northwestern.

Allen Barra: Let me start out by reading to you a quote about Shakespeare by one of your and my favorite writers: “The sane man who is sane enough to see that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare is sane enough not to worry whether he did or not.”

Garry Wills: That was G.K. Chesterton. I guess worrying about it is better than denying it. You can make people spend a lot of energy debating the question. I think that was GKC’s way of saying that no matter who wrote it, it was Shakespeare.

AB: Early in “Making Make-Believe Real,” you hit us with an intriguing thought: “It may not be entirely fanciful to look at the whole Elizabethan endeavor as the work of an experimental troupe.” Could you expand on that a bit?

GW: Elizabeth was a woman, after all, crowned when the Bible said women should not rule. She was disowned by her father, Henry VIII, as the bastard child of another man. As a girl, she had been imprisoned in the Tower of London. And that was just the beginning of her troubles.

Protestants didn’t regard Elizabeth as being protestant enough, she wasn’t Catholic enough for conservatives, and she wasn’t married, which displeased those who wanted an heir to succeed her. She wasn’t war-like enough for those who wanted war with Spain.

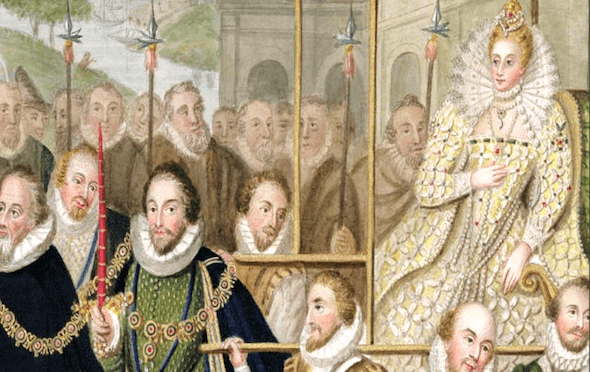

She had to experiment with ways of creating the illusion of power. Some things worked and some things didn’t — she experimented. What’s astonishing is that she put on such an immensely impressive show, partly because she was able to make rich people finance everything — naval exploits, processions, tournaments, plays. She put minimal expenditure into all of those things, and she and her supporters and the rich people themselves knew they had to mount a show for their own advance but also for the advance of the Reformation and the Catholic Church they were overthrowing. Very much like experimental theater, I think.

AB: How Catholic was Shakespeare and, for that matter, how Catholic was Elizabeth?

GW: In my book I refer to the Shakespeare scholar Clifford Geertz, who thought that Elizabeth’s rule maintained a sacredness even after Catholic rituals had been abandoned. I believe those were the only vestiges of Catholicism that Elizabeth was really interested in.

I don’t think Shakespeare was very Catholic, though his father was. In “Macbeth,” Shakespeare manipulated his audience’s fears of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. [A handful of plotters came very close to blowing up the king and his heir, the prince, as well as all members of the court and parliament.] You have to understand that to Shakespeare’s audiences, this carried the same kind of shock and dread that Americans felt after Pearl Harbor or the assassination of Kennedy. And not just the common people: Great poets such as John Donne and John Milton took the Gunpowder Plot quite seriously.

The denunciation of the Gunpowder Plot focused heavily on Jesuits, who were believed to have taught Catholics how to give misleading answers when questioned about their faith. It would not be out of line to liken the fear of Catholicism in Shakespeare’s time to the fear of Communism in, say, the 1950s.

Charges of magic and witchcraft had been leveled at the Jesuits for years because of their use of healing relics, icons and exorcisms, and Shakespeare knew of the attacks on Jesuits as dealers in witchcraft. So political witchcraft was a lively topic in 1606. Shakespeare’s witches aren’t just emanations of Macbeth’s inner state: They were vivid symbols of something his audience feared. They understood that, as the Bible says, “Rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft,” and that the witches prompt Macbeth to regicide — which everyone knew the Jesuits were guilty of.All this is a roundabout way of saying that I don’t think anyone who made fun of the Gunpowder plotters the way Shakespeare did in “Macbeth” had any Catholic instinct.

AB: You write that “Elizabeth loved drama.” I guess that makes her history’s first drama queen. Can you put her love for drama in a nutshell?

GW: Start by remembering that the commercial theater at the Globe or Blackfriars or elsewhere was not confined to tragedy and comedy. Theater troupes were supported by peers as a way of pleasing the queen, at whose court they regularly appeared.

AB: And the queen loved them. …

GW: Very much. These performances were frequent and received with much enthusiasm. Elizabeth often saw six or more plays at Christmastide. Imagine so many plays being staged at today’s White House, or even in the court of Elizabeth II. …

AB: But to Elizabeth and the court, these were much more than entertainments. …

GW: Much more. They were not frivolous entertainments or ornaments. They were the expression of a period in transition, trying to articulate its own meaning to itself.

AB: I’d like to talk about your interpretations of two of Shakespeare’s most popular plays from the perspective of Elizabeth.

First, would it be safe to say your sympathies lie more with Hal than Falstaff?

GW: (Laughs) That would be extremely safe to say.

AB: You’re not in the majority of critics of “Henry V.”

GW: I don’t see that Shakespeare wrote “Henry V” as a defense of imperialism. His protagonist is a searching king, a self-questioning man finding his way in an imperfect world without any illusions about that fact. Among Hal’s detractors, even the winning love scene that ends the play has been called a “political rape.” Katherine is given no choice in the matter — her father has given her away for political reasons.

But all royal marriages at that time were arranged, so it doesn’t seem right to single out Henry on this count.

The question Shakespeare asks is whether one could find love within those cultural constraints. The test for Henry is not to win Katherine’s father over, as that has already been accomplished, but her love.

This, I think is what “Henry V” is about: how a king can humanize the role of a king despite the constraints of power and position.

AB: How would you relate this to Elizabeth?

GW: Elizabeth’s story is quite similar — she wins love from a country that would submit more reluctantly to her successor, James I.

AB: I like the way you close the chapter: “She wooed and won a people as Henry woos and wins Kate. They both made make-believe monarchy believable.”

I also want to mention “The Taming of the Shrew.” It has become commonplace today to call it “sexist.” You strongly disagree with this. …

GW: It’s a shame that so much modern discussion of “The Taming of the Shrew” now circles warily around the issue of misogyny; exoneration for Shakespeare and Petruchio is uneasy at best. I think a clue to what Shakespeare really meant is that the tool that Petruchio uses for taming Kate isn’t imprisoning, torturing or whipping. Petruchio’s weapon is courtly love. When she slaps him he responds by embracing her.

AB: “Her curses are for him sweet singing, her frowns are morning roses sweet with dew.”

GW: I think those directors who have Petruchio wielding a whip in dealing with Kate are misinterpreting their subject.

AB: So you disagree with Zeffirelli’s production with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor knocking each other about?

GW: It’s as if they were still playing the characters in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” I agree with Ann Thompson [Shakespeare scholar who edited “The Taming of the Shrew (The New Cambridge Shakespeare)“] in preferring John Cleese’s more nonchalant approach in the BBC production. …

AB: John Cleese of Monty Python?GW: Yes, it’s a wonderful production. It’s probably the best interpretation of Petruchio that I’ve seen. The anger Cleese puts on is all directed at others when he thinks they are insulting Kate, offering her inferior food or whatever. He satirizes her own beating of her sister and her servants, and it’s a sign of her changing character when she pleads with him to stop beating the servant. Ann Thompson is one of the few to make note of the fact that Petruchio shares Kate’s deprivations of sleep and food.

Shakespeare often showed men and women who engage in insults while they are steadily falling in love with each other — such as Beatrice and Benedick [“Much Ado About Nothing”] and Rosaline and Berowne [“Love’s Labour’s Lost”].

I think that any version of “The Taming of the Shrew” must take in to account the power of courtly love. Elizabeth’s Reformation Court had to replace devotion to the Virgin Mary and other Catholic saints with a comparable personal link to one’s idol. Courtly love was a perfect vehicle, and thus “Taming of the Shrew” is a perfect example of Elizabethan temperament. Kate’s speech at the end is the greatest defense of Christian monogamy that has ever been written.

AB: You insist that the Kennedy years do not deserve to be associated with Camelot. You write, “Jacqueline Kennedy and Theodore H. White tried to throw a posthumous glow of Camelot over the Kennedy presidency, with Pierre Salinger as court jester, Theodore Sorensen as poet laureate, Robert Kennedy as the knight in armor, and Messrs. Schlesinger, Galbraith, Rusk, McNamara as wise men of the round table. But this was a late and thin bit of mythologizing … to recast Kennedy’s less-than-a-term presidency from such meager mythical materials was not very convincing.”

Elizabeth’s reign, you feel, was much more deserving of the comparison with Camelot.

GW: Certainly, Elizabeth’s 45 year rule had far more time and far deeper cultural sources to draw on. She was elevated not by just a few partisans and not after she was gone, but by many up and down the social scale from peasants to the nobility and across the political-religious spectrum. They all believed that the nation’s prosperity — and their own — rested on putting a legendary spell around her.

Ruling from this mythical cover, she worked to attain her religious, political and economic goals. She used poetry to serve policy and did it better than any ruler before or after.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.