|

To see long excerpts from “A Broken Hallelujah” at Google Books, click here.

|

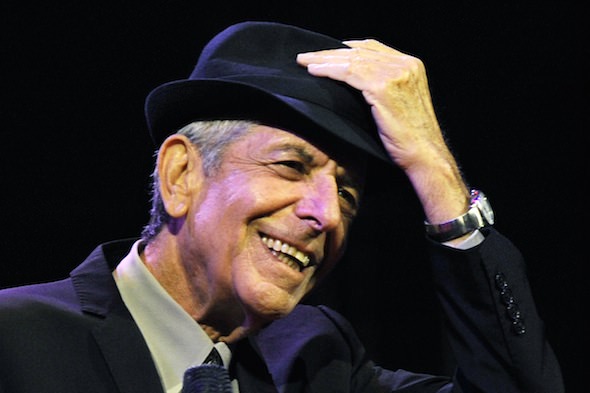

“A Broken Hallelujah: Rock and Roll, Redemption, and the Life of Leonard Cohen”

A book by Liel Leibovitz

There are surely some Americans who have never heard of Leonard Cohen. Then there are those who remember his early songs, like “Bird on a Wire,” popularized by Judy Collins in 1968, but who dismiss him as a poet/songwriter of despair and depression. Finally, there are the millions of fans, and I count myself among them, who experience his music and lyrics as authentic expressions of their own lives.

Liel Leibovitz, with “A Broken Hallelujah: Rock and Roll, Redemption, and the Life of Leonard Cohen,” has written an elegant, beautifully crafted book that Cohen’s fans will instinctively understand. It is not a biography, though he does recount Cohen’s loss of his father at age 9, his lifelong struggle with depression, decades blurred by alcohol and drugs, his life in Cuba just days before the revolution began, his efforts to sing and lift the spirits of Israeli soldiers during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the five years he spent in a Buddhist monastery, and his astonishing comeback in his mid-70s as a global troubadour whose concerts, held in huge arenas around the world, have given him a stardom he never expected.

Nor is it a discography, though Leibovitz uses newly available private letters and journals to explain the ups and downs of Cohen’s remarkable career in studio recordings and promotional tours. Rather, “A Broken Hallelujah” is more of an exploration of the literary and spiritual traditions that shaped Cohen, as well as a portrait of a person who could be cocky and arrogant, witty and ironic, angry and tender, and quite often, the unfailingly polite gentleman.

At age 15, Cohen stumbled upon the great Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, whose “central artistic engine” was duende, often described as “deep song” or “soul.” Goethe described it as “that profound and nebulous sadness we all feel but can’t easily articulate.” In Lorca, Leibovitz writes, “Cohen glimpsed his own state of mind, reflected back at him in beautiful verse, rich with intricate imagery, elegant and gloomy.”

In Leibovitz’s view, Cohen’s success — spanning more than four decades — rests on how his lyrics, like those of Lorca, bypass our rational self and touch our soul. Cohen comforts our existential loneliness, acknowledges our emotional confusion and reflects our search for truth, as well as our outrage at injustice. With Cohen’s songs as the soundtrack of our lives, we experience the universal feelings of lust, love and loss. Through his prophetic songs, we search for redemption, even though Cohen insists that God may not be listening. Still, he encourages us to carry on with humor and honesty and insists, in his 1992 song “The Future,” that “love’s the only engine of survival.”

Many Americans don’t realize that Cohen, a Canadian, was a highly acclaimed poet and novelist long before they heard his songs about Suzanne’s odd habits or his farewell to Marianne. The son of a wealthy Jewish family in Montreal, he began his nightly wanderings at a young age through the seedy streets of downtown Montreal. In his search for adult guidance, he turned to poets, and to Jewish thinkers who disagreed with one another but who also taught him to embrace a faith that asks its believers to question everything but their own tradition.

As Leibovitz notes, Cohen was always out of sync with the times. He was too young for the Beats, too old for the youth of the ’60s. He fled both Canada and Judaism and exiled himself on Hydra, a primitive Greek island, where he lived with a Norwegian woman, the famous “Marianne.” But even in exile, the troubadour tradition of Montreal and the contradictions of Judaism and other spiritual traditions threaded themselves throughout his poetry and songs.

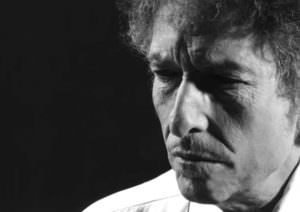

In the late 1960s, Cohen arrived in New York. Leibovitz describes how much Robert Zimmerman — a young Jewish man from Minnesota, who reinvented himself as Bob Dylan — influenced Cohen, who lived in the famous Chelsea Hotel where Dylan and other musicians and artists were nurturing new forms of musical and artistic expression. Cohen began writing songs.For most of the 1970s and 1980s, Cohen was once again out of sync with the music scene. He searched for simplicity. He recoiled from progressive rock, punk rock, loud bands, smashed guitars, too many instruments and trucks bulging with electronic equipment.

Cohen was never a rocker, and the misleading subtitle of this book falls flat. Tellingly, the British edition of Leibovitz’s book has as its subtitle, “Leonard Cohen’s Secret Chord,” a reference to the first verse of his signature song, “Hallelujah,” which begins with the words, “I’ve heard there was a secret chord that David played, and it pleased the Lord.”

For nearly two decades, Cohen, the balladeer, worked hard, sometimes taking years to write a song. But he was estranged from a pop and rock culture that had little to do with the poetic ballads, songs of love and lust, and spiritual chants that characterized his songs. Cohen wanted intimacy with his audience. He was famous in Europe, but Americans were not yet ready.

Nor was Cohen, but gradually — despite depression and alcohol and drugs — he found his voice, one that can best be described as a prophet’s. Leibovitz captures the power of Cohen’s verses with considerable insight. “They were cluster bombs,” he writes. “They dropped fast, penetrated deeply, and set off a series of ongoing explosions that resonated long after they were first heard.”

Like a fine novelist, Leibovitz shows, rather than tells, how Cohen charmed and baffled both interviewers and his audience with irony, humor and quips that seemed incomprehensible, and yet came off like revelations. On one occasion, an interviewer asked Cohen about his “concerns”:

“Leaning forward, picking up steam as he spoke, Cohen replied. ‘I’m bothered,’ he said, ‘when I get up in the morning, my real concern is to discover whether or not I’m in a state of grace. And I make this investigation, and if I’m not in a state of grace, I try to go to bed.’ ”

Leibovitz comments:

“It’s a charming statement, and its vague absurdity helps it linger for a spell longer than a quip usually does. It compels you to imagine what a state of grace might feel like, and why, really you should bother getting out of bed graceless at all. The sound bite blossoms into a moment of meditation; that’s as great a poetic achievement as any carefully wrought stanza.”

The young Cohen was vain and a master at performing “cool.” At a news conference when he was 30, “he wore a tight leather jacket and a skinny black tie, and the cigarette dangling from his mouth at a sharp angle made him look less like a person and more like a collection of straight lines that had temporarily coalesced into human form.” In 2008, when he was in his mid-70s, he adopted a dapper suit with a fedora tilted at just the right angle and appeared as the ultimate polite and humble gentleman. “ ‘This is the first time in 14 years I have stood before you in this position as a performer,’ ” he said to the millions who heard this ageless man sing. “Back then, he joked, ‘I was just a kid of 60 with crazy dreams.’ ” Leonard Cohen was a master at “performing” Leonard Cohen.

By the 1990s, Cohen introduced himself to a new generation with two albums — “I’m Your Man” and “The Future” — that included some of his finest work. Now surrounded with exceptionally talented musicians and female backup singers, Cohen’s gravelly voice described life and love in a degraded society that glorified cocaine and agreed that greed was good. Some of his songs seemed like prayers. As Leibovitz notes, “ ‘If It Be Your Will,’ for example, perfectly mimicked the cadences and preoccupations of Jewish prayers. ‘If it be your will,’ Cohen sang, ‘If there is a choice/Let the rivers fill/Let the hills rejoice/Let your mercy spill/On all these burning hearts in hell/If it be your will/to make us well.’ ”

In “Anthem,” Cohen also wrote as a prophet, urging his audience to “Ring the bells that still can ring.” Yet he softened his message with an optimistic image that also derived from the Jewish tradition: “There is a crack, a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.”

Without doubt, it is “Hallelujah” that is most associated with Cohen. Dozens of singers have recorded versions of the song. It has appeared on the soundtrack of “Shrek” and many other films. And k.d. lang opened the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics with “Hallelujah.”Redemption, as Leibovitz writes, was “the one theme that, with slight variations, would consume [Cohen] throughout his career. … Redemption was a discretely Jewish affair, a wholly Canadian affliction, an entirely universal obsession. It was more than enough for a lifetime of work.”

The song ends with a confession, coupled with the recognition that although redemption may not be possible, we can still praise the wonder of life and love: “I did my best, it wasn’t much/I couldn’t feel so I tried to touch/I’ve told the truth/I didn’t come here to fool you/And even though it all went wrong/I’ll stand before the Lord of Song/With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah.”

Leibovitz has written an original and captivating book about one of the greatest poet/singers. I don’t know whether readers who are unfamiliar with Cohen’s poetry songs will be able to “hear” the musician’s quest for grace and redemption. But since he has millions of fans, this book will not lack for readers.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.