A Bomb Blast That Still Echoes, a Half-Century Later

The bombing deaths of four Birmingham girls on this day 50 years ago changed the nation's outlook on civil rights. But did it lead to real change?

On this day fifty years ago, a box of dynamite rigged to a timer exploded beneath a stairway at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., just as a group of African-American children were heading inside to prepare for Sunday morning services. Four girls were killed, more than a score more were wounded, and the South’s long intransigence against equality for African-Americans took yet another deadly turn.

This time, though, the nation, paid attention — well, at least the non-South part of the nation did. The bombing, part of a vicious summer in the civil rights struggle, invigorated the movement. But it would be years before the bombers were brought to justice, and even now, author and journalist Diane McWhorter reports in The New York Times, her native city of Birmingham still has yet to come to grips with its past sins. A half-century later, local commemorations mark the anniversary, but reparations have never been paid to the families of the dead children, nor to those who survived with scars and medical bills and, in the case of Sarah Collins Rudolph, sister to one of the dead girls, a lost eye.

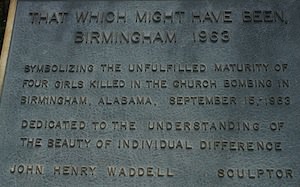

Last week, Congress, in a rare moment of unanimity, bestowed its Congressional Gold Medal, its highest civilian honor, on the four dead girls, Denise McNair, then 11, and Addie Mae Collins (Sarah’s sister), Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley, who were 14 when they died. Note that it took a 50th anniversary for Congress to honor those innocent victims. As McNair wrote, Rudolph initially planned to skip the ceremony (she eventually went) to let “the world know, my sister didn’t die for freedom. My sister died because they put a bomb in that church and they murdered her.” Reparations are overdue, she said, a point McWhorter also makes:

In the wake of the attacks on the Boston Marathon and the World Trade Center, an outpouring of financial aid for the victims expressed a belief that their suffering was a sacrament of our democracy. Yet Sarah Collins Rudolph — maimed by native-born terrorists in our nation’s great internal freedom struggle — has been expected to deal with protracted medical and cosmetic issues, to say nothing of other forms of anguish, on a domestic worker’s wages.

This anniversary, McWhorter says, was an opportunity missed.

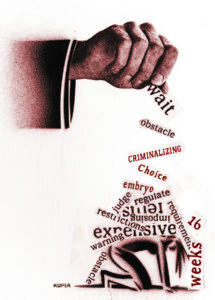

The Congressional leaders’ bipartisan homage to “the four little girls” could not overcome the unintentional theme of this anniversary year: half a century after the prime of the civil rights movement, why does so much of its promise remain unfulfilled, the sacrifice unrequited? The recent 50th anniversary celebrations of the March on Washington were mocked by the Supreme Court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act and the violent death of yet another black innocent, Trayvon Martin.

We are understandably drawn to cheaper correctives: posthumous pardons for the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama; plaques at the Birmingham city hall dedicated, in August, to Virgil Ware and Johnny Robinson, two other black children killed by whites on Sept. 15, 1963. If the structural changes achieved by these symbolic gestures are roughly none, their appeal is that they also cost nothing.

That bloody summer of 1963 — which McWhorter detailed in her 2001 book, “Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama: The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution” — was a pivotal experience for the nation, and helped pushed the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law. But it also was only part of a long arc of the troubled history of race relations in the country. At The Atlantic, Andrew Cohen writes of white Birmingham lawyer Charles Morgan Jr., who, a day after the bombing, issued an eloquent plea for white Alabamans to shoulder the blame for the region’s heinous acts of racism. Morgan’s speech included a challenge to his fellow white citizens who kept asking, “Who did this?”

Who is guilty? A moderate mayor elected to change things in Birmingham and who moves so slowly and looks elsewhere for leadership? A business community which shrugs its shoulders and looks to the police or perhaps somewhere else for leadership? A newspaper which has tried so hard of late, yet finds it necessary to lecture Negroes every time a Negro home is bombed? A governor who offers a reward but mentions not his own failure to preserve either segregation or law and order? And what of those lawyers and politicians who counsel people as to what the law is not, when they know full well what the law is?

Those four little Negro girls were human beings. They had lived their fourteen years in a leaderless city: a city where no one accepts responsibility, where everybody wants to blame somebody else. A city with a reward fund which grew like Topsy as a sort of sacrificial offering, a balm for the conscience of the “good people,” whose ready answer is for those “right wing extremists” to shut up. People who absolve themselves of guilt. The liberal lawyer who told me this morning, “Me? I’m not guilty!” he then proceeding to discuss the guilt of the other lawyers, the one who told the people that the Supreme Court did not properly interpret the law. And that’s the way it is with the Southern liberals. They condemn those with whom they disagree for speaking while they sit in fearful silence.

Morgan eventually was hounded out of town by death threats.

To be sure, Birmingham and the nation have changed over the past five decades, and the improvements in racial equality can be measured by laws such as those guaranteeing access to the voting booth — a guarantee that is crumbling away in places — and barring segregation. But with statistics measuring wide racial gaps in employment levels, income, health care access, incarceration rates and local schools, you have to wonder whether the strides taken over the last 50 years are mere baby steps.

—Posted by Scott Martelle.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.