A Black Voter Suppression Slap in the Face

Political justice in Jackson, Mississippi looks a lot like it did in the 1950s. Sen. John Horhn, D-Jackson expresses the Mississippi Legislative Black Caucus' disappointment at the passage of House Bill 1020 at the Mississippi Capitol, Wednesday, Feb. 8, 2023. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Sen. John Horhn, D-Jackson expresses the Mississippi Legislative Black Caucus' disappointment at the passage of House Bill 1020 at the Mississippi Capitol, Wednesday, Feb. 8, 2023. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

“The name of this tune is Mississippi Goddam, and I mean every word of it.”

—Nina Simone, “Mississippi Goddam”

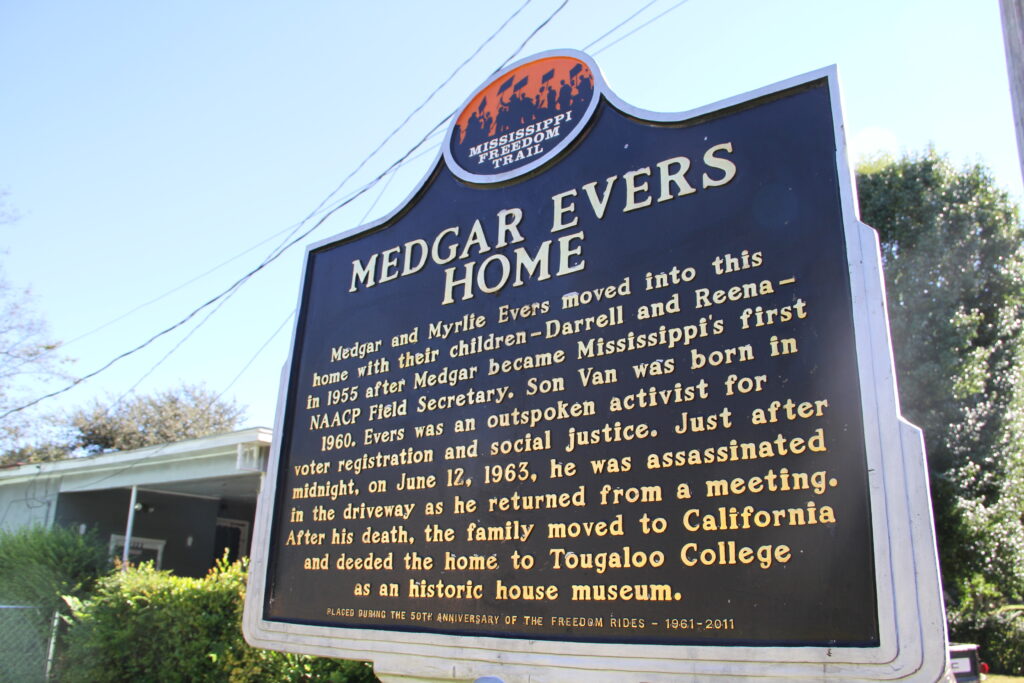

I didn’t cry when I learned that Nina Simone’s iconic song “Mississippi Goddam” was inspired by the 1963 murder of Medgar Evers. My tears would come later, after learning that Evers’ 8-year-old daughter Reena — the same age as my own daughter Harlem — watched her father bleed to death in the driveway of their home in Jackson, Mississippi.

The civil rights and voting rights leader was killed by a rifle blast in the back by White Citizen Council member Byron De La Beckwith. During the second of two 1964 trials in Jackson, Gov. Ross Barnett entered the courtroom and shook De La Beckwith’s hand in front of the jury. De La Beckwith was also seemingly on good terms with presiding judge Leon Hendrick, who released him on bond after declaring a mistrial when 10 hours of deliberation led to a hung jury.

The jurors — and Judge Hendrick — were all white men. Jurors are drawn from voter rolls and judges are elected, so the systemic Black voter suppression of 1960s Jackson meant justice would be suppressed for Evers and his family — including his daughter.

Recently, Mississippi’s white political class has been reminiscing about these good ol’ days of political justice — and its antecedent Reconstruction. This may be why white elected officials are trying to recreate the era in Jackson — the state’s capital — by passing the GOP-sponsored House Bill 1020 almost exclusively along party and racial lines. HB 1020 relies on a legal maneuver that empowers white GOP officials to sidestep the will of Jackson’s Black voters by appointing judges (local judges are typically elected by local residents) within a city that is nearly 83% Black.

“Mississippi has a long history of voter suppression in Black communities,” long-time Jackson activist and writer Charlie Braxton told Truthdig. “The current GOP Mississippi legislature is all-white and their attitude is reminiscent of Mississippi during Reconstruction. They want to return Jackson to the 1950s.”

HB 1020 is a Reconstruction-era bill, a Byron De La Beckwith handshake and a Black voter suppression slap in the face — all rolled into one.

Reconstruction, the period directly following the Civil War from about 1863 to 1877, was defined by white lawmakers suppressing Black voters to maintain political control over local Black populations — including Black folks seeking justice in politically-tainted courtrooms. Mississippi was a leader in violence and inequity during Reconstruction and what followed.

HB 1020 relies on a legal maneuver that empowers white GOP officials to sidestep the will of Jackson’s Black voters.

In 1890, white legislators rewrote the state constitution to legally block Blacks from exercising 14th Amendment voting rights by requiring a (selectively enforced) poll tax and literacy test. “Every elector shall, in addition to the foregoing qualifications, be able to read any section of the constitution of this State; or he shall be able to understand the same when read to him,” the new constitution demanded — along with two dollars — from Black residents who had previously been forbidden to read and make income. Following Mississippi’s voter suppression lead, new constitutional statutes suppressing the vote were enacted in South Carolina (1895), Louisiana (1898), North Carolina (1900), Alabama (1901), Virginia (1901), Georgia (1908) and Oklahoma (1910).

During the recent floor debate over HB 1020, Mississippi Democratic house representative Ed Blackmon said, “This is just like the 1890 Constitution all over again.” Representative Blackmon, who is also a civil rights activist with a long record of championing voting rights, connected the bill to the state’s history of voter suppression. “Only in Mississippi would we have a bill like this … where we say solving the problem requires removing the vote from Black people.”

Similar to the socio-political environments of Reconstruction and the 1960s, Black Mississippians are out-flanked and out-gunned by white supremacist actors, but their resistance efforts are strong. With the white-led HB 1020, SB 2113 (restricting how race can be discussed in schools) and HB 370 (creating a legal maneuver for the GOP to remove Jackson’s current Black mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba), Braxton said there is a feeling among Jackson’s Black residents that they are under siege by the state’s white power brokers. And he senses that Black folks are up for the fight against white supremacy.

Black Mississippians are out-flanked and out-gunned by white supremacist actors, but their resistance efforts are strong.

African American studies professor Akinyele Umoja told Truthdig that local Mississippi leaders have historically led resistance efforts against white supremacy. Yet, current Jackson leaders need more national support. “Local leaders have been courageous and strategic in fighting to retain control over Jackson’s schools, in fighting to provide clean water and in fighting to control the airport, but they really need more national support and national resources,” she said. Umoja, who is the author of 2013’s “We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance and the Mississippi Freedom Movement,” said “We all need to do a better job of supporting the Jackson resistance efforts. We need to focus on helping them gain political and economic power. We can’t have GOP governments trying to strip Black municipalities of their power.”

The biggest airport in Mississippi is located in Jackson. It’s a major source of local revenue, which could potentially be enhanced further with development. Braxton said the GOP has been trying to strip it from Black control, but Mayor Lumumba has resisted those efforts. Umoja, who has frequently used Jackson-Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport, said he’s heard the airport staff talk with pride about the well-run airport being named after the civil rights and voting rights leader.

An international airport is a powerful symbol for a man who dedicated his life to uplifting Black folks in the fight against white supremacy. Evers was a man of dignity who gave his life for human freedom, who gave his life for the soaring idea of justice and bequeathed this idea to his children.

Three weeks before the 2020 election, Reena Evers-Everette, the executive director of the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute, was scheduled to speak about the importance of voting and voter suppression. A few months earlier she had movingly ended an op-ed by quoting her mother: “You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea.” On this sunny October day during election season, the daughter of Medgar Evers approached a microphone set up in the front yard of her childhood home, a few feet from where she saw her voting rights advocate father bleed to death, for a soaring idea. With obvious pain and conviction in her voice, Evers-Everette added her own symbolic verse to “Mississippi Goddam” by saying, “The sacrifices that so many have made will be in vain — if we don’t go out and vote.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.