4 3 2 1

In his new novel, Paul Auster manages to conjoin gimmickry and genius, as readers find their perspective radically altered by a detail unveiled at the end.

Henry Holt and Co.

| To see long excerpts from “4 3 2 1” at Google Books, click here. |

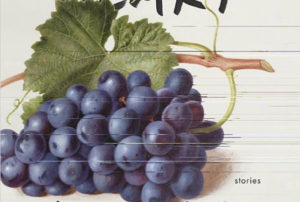

“4 3 2 1” A book by Paul Auster

In “4 3 2 1,” Paul Auster manages to conjoin gimmickry and genius. Not only that, but except for those who choose to dive into spoiler-heavy reviews such as this one before moving on to the novel, readers will find their perspective radically altered by a detail Auster unveils at its end. So much so that some may well go back for a second perusal – a phenomenon most authors spend their lives wishing for. It’s no mean undertaking, given that “4 3 2 1” comes close to a whopping 900 pages.

Archie Ferguson, born in Newark in 1947 to culturally Ashkenazi Jewish but religiously nonobservant parents, comes of age in one of several locations in the Garden State … or else in New York City. During his childhood, his father dies in a suspicious fire at the furniture, appliance and electronics store he and his two brothers own … or he isn’t anywhere near the place at the time. A witty and politically attuned young woman named Amy becomes Archie’s girlfriend, or his step-cousin, or his stepsister. After high school, he relocates to Paris to soak up French culture and work on a book, unless he remains in the U.S. and enrolls in either Columbia or Princeton.

Got all that? On the face of it, the gimmick out of which the author constructs “4 3 2 1” appears unoriginal. In much of his fiction, beginning with “The New York Trilogy” (1987), Auster has wrestled with the tentacles of chance, which can jigger your frame of mind, scramble your plans, and prompt you to traverse this instead of that path, sometimes with momentous consequences. At first blush, it seems that “4 3 2 1” simply takes this preoccupation to an extreme.

Like just about everyone’s life, Archie Ferguson’s could have – in theory – turned out any number of ways. Auster maps out four such trajectories. (For some reason, he doesn’t arrange the text in the manner of one completed version of Archie’s life after another, but rather the first chapter of the first version followed by the first chapter of the second version, and so on, meaning that in order to trace one trajectory all the way through to its end, you have to skip over intervening material between chronological chapters.) In the early going, “4 3 2 1” resembles a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure book that enables the reader to participate in the story by repeatedly choosing from several options for advancing the plot, except here you select only the beginning and then see where it leads.

The novel’s unique conceit, made manifest only at its very end, is that the four written versions of the protagonist’s life were penned by the guy himself, and that one is true while the others are imagined. For Archie, “the torment of being alive in a single body was that at any given moment you had to be on one road only, even though you could have been on another, traveling toward an altogether different place.” So he decided to “invent three other versions of himself and tell their stories along with his own story … and write a book about four identical but different people with the same name: Ferguson.”

It might never have occurred to you that this is the case (for one thing, all four versions are narrated in the third person), but the setup proves plausible. In all four renditions of Archie’s life, even the one in which he dies at the tender age of 13 (the three others take the story up to his early 20s), he is intrigued by “what if” scenarios. Plus, he demonstrates avidity for reading as well as writing, a “compulsion for filling up white rectangles with row after row of descending black marks.”

Crucially, Auster reveals which account of Archie’s life is true. In doing so, he supplies the reader with material to interpret the three other versions in a manner far more penetrating than would have otherwise been possible. For example, in the story variant that you learn is in fact Archie’s autobiography, Amy becomes his stepsister and, despite or perhaps because of her affection for him, she prevents their relationship from taking the romantic turn he so desires. Knowing that this happened in Archie’s real life demands a reconsideration of those versions of the story in which the two do not become step-siblings and consequently give free rein to their amorous feelings for each other. Indeed, it now becomes apparent that Archie has long fantasized about such an alternative scenario.

The process works the other way around, too; certain story elements in the fictional versions of Archie’s life will induce you to examine the autobiographical account in a new light. What to make of the bisexual Archie in one of the three invented chronicles? Is he the real Archie’s alter ego? Do the explicit descriptions of sex with men reflect the real Archie’s desires – and can you glean as much from the autobiographical version, thanks to little indications tucked into corners that you failed to notice when reading it the first time?

For this reviewer, discovering that the version featuring the gay relationships springs from Archie’s imagination led to a revised evaluation of its content and structure. At first, the frequency with which people encountered by Archie turn out to be gay or bisexual struck me as statistically improbable – and I faulted Auster for this. I changed my opinion upon learning that, in the world Auster creates for the novel, these characters are drawn by a young writer inexperienced in the art of crafting fiction. Perhaps such a judgment is generous, but I can’t shake the possibility that Auster intends for this version to represent a fledgling and contemporaneous writer’s attempt (sincere yet flawed) to explore sexual repression in the 1960s.

The turbulence of that decade, with the civil rights movement and strained race relations, the assassination of JFK, the Vietnam War and the ever-looming military draft, figures prominently in the versions that advance into the protagonist’s adulthood. And as the four avatars of Archie Ferguson progress along their respective trajectories and are reduced to three, another significant feature of the story comes into relief. For all the differences in his immediate circumstances, Archie is the same person across “4 3 2 1.” It’s not just the aforementioned allure that “what if” scenarios hold for him, or his bookish inclinations. He possesses the same longing for justice, the same restlessness within his social and class confines, and the same “delirium of becoming a man without the privileges of being a man.”

At times, Auster’s laundry lists of books (mostly novels and poetry) as well as films that enthrall the intellectually voracious Archie end up grating a bit. And the excerpts from Archie’s own writing projects in each of the four sections sometimes come across as pretentious – though, again, this may have been Auster’s intention. Fortunately, throughout “4 3 2 1,” Auster’s prose generally remains at once fluid and precise. And in quadrupling his protagonist and leading him down different paths, the author ensures that, despite the novel’s monumental length, Archie seldom bores the reader.

Moreover, upon reaching the end of “4 3 2 1,” you feel intimately acquainted with the young man. How so? To begin with, by this point Auster has revealed that one of the four renditions of Archie’s life is true (pinpointing the one in question), and that Archie authored all of them. In addition to retroactively altering your perception of the narrative, this information enables you to better parse the many layers of the story. Yet the author’s last-minute game-changer goes further, by making you aware of the true depth of your familiarity with the protagonist’s psyche. Having read the four constituent elements of this one-of-a-kind novel, you now realize that not only do you know what Archie did, you know what he thinks he would have done in wholly imagined situations.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

4 3 2 1

4 3 2 1

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.