1968 ‘Black Power Salute’ Sparked Ongoing Miscarriage of Justice by U.S. Olympic Committee

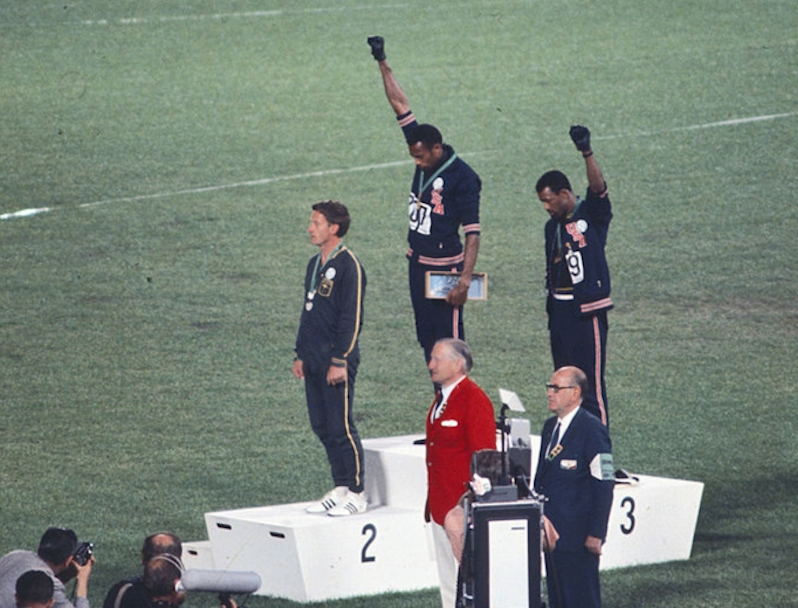

The silent gesture by medalists John Carlos and Tommie Smith was meant to raise awareness of human rights, not dishonor the flag. Both men deserve an apology for how they have been treated. From left on the 200-meter medal stand at the Mexico City Olympics: Australian Peter Norman and Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos. (Angelo Cozzi / Wikimedia Commons)

1

2

From left on the 200-meter medal stand at the Mexico City Olympics: Australian Peter Norman and Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos. (Angelo Cozzi / Wikimedia Commons)

1

2

From left on the 200-meter medal stand at the Mexico City Olympics: Australian Peter Norman and Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos. (Angelo Cozzi / Wikimedia Commons)

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.