The Fight Over Mauna Kea Is About More Than a Telescope

The rights of Hawaiian indigenous peoples are at stake as local government officials, astronomers, residents and activists take sides. Demonstrators gather to block a road at the base of Hawaii's tallest mountain in July in Mauna Kea, Hawaii, to protest the construction of a giant telescope on land many Native Hawaiians consider sacred. (Caleb Jones / AP)

Demonstrators gather to block a road at the base of Hawaii's tallest mountain in July in Mauna Kea, Hawaii, to protest the construction of a giant telescope on land many Native Hawaiians consider sacred. (Caleb Jones / AP)

Hawaii Gov. David Ige this week rescinded his emergency proclamation aimed at thwarting native Hawaiian protesters and granted the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) Observatory a two-year extension to begin construction on Mauna Kea, one of two mountains on the Big Island of Hawaii. The move is a partial victory for the indigenous-led movement opposing the TMT. For weeks now, native Hawaiians have blockaded a road leading up to the summit, preventing workers from breaking ground. Ige explained he wants to “find a peaceful solution to move this project forward” and “deescalate things.”

The battle between astronomers and indigenous Hawaiians over Mauna Kea began decades ago. Even before the TMT was a full-fledged project, Hawaiians objected to the desecration of their sacred space, on which 13 observatories already operate. Although I am not native to Hawaii, it is also a personal story for me. From 1996 to 1998, I attended the graduate program at the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy (IfA) and was one of a small crop of privileged astronomy students, professional astronomers and technicians who were allowed to step onto Mauna Kea’s pristine snow-capped summit and use the observatories. For astronomers, Mauna Kea is the ideal location, with an altitude above cloud cover and its extremely dry weather that offers a low-moisture view through the atmosphere.

Over the course of my two years at the IfA, I went on several observing runs on the summit, thrilled to gather data from the powerful telescopes that dotted the red dirt. Not once during my training was I told of the importance of Mauna Kea to native Hawaiians. The first time I heard about it was at a campus talk given by one of the Trask sisters—I cannot remember now if it was Mililani or Haunani-Kay, considered the founders of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement—who debated an IfA astronomy professor over the use of Mauna Kea for astronomical observations. It was an eye-opening experience and an early part of my political education.

Kealoha Pisciotta is a practitioner of traditional and customary cultural and religious practices relating to Mauna Kea. Once upon a time, she, too, used the observatories on Mauna Kea, working as a telescope operator for 12 years. Today, Pisciotta is the president of Mauna Kea Anaina Hou (MKAH), the group that has brought multiple legal challenges against the TMT, which would be North America’s largest and most expensive telescope project. Last fall, Hawaii’s Supreme Court ruled in favor of the TMT, which led to the current wave of protests against the start of construction. In an interview about the latest activism, Pisciotta explained to me that for native Hawaiians, Mauna Kea is “our origin place. It’s where we believe all of man came from, and it is the home of our deities from the creator to all of our gods and goddesses.” In addition, Mauna Kea is “a burial ground of our most significant and revered ancestors, including navigators that discovered Hawaii thousands of years ago.”

Pisciotta says she descends from navigators, and during her time as a telescope operator on Mauna Kea she loved her work. But eventually she found herself on the opposite side of those who claim a right over the sacred mountain. “The TMT has alternatives,” she explained, “but we don’t.” Indeed, there have been several alternative sites proposed for the TMT, including the Canary Islands and Chile. Pisciotta says she does not call for the dismantling of the existing 13 observatories on Mauna Kea, but she and others draw the line at the TMT. A good analogy for their demand is the climate justice movement’s call for “no new fossil fuel infrastructure” as part of the transition to renewable energy.

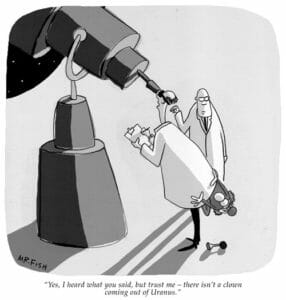

Hawaiians want no new telescopes on Mauna Kea, and they have a moral right to make that claim. According to Pisciotta, it is about “our right to religious freedom.” There have been attempts to cast the opposition to the TMT as “anti-science,” or as a battle between religious irrationality and rational inquiry into our natural world. But activists in the movement rarely, if ever, express opposition to scientific research. The TMT represents the latest assault on the rights of indigenous Hawaiians, whose rights have been marginalized in favor of corporate, colonial and military interests for far too long.

One Hawaiian writer, Trisha Kehaulani Watson, placed the struggle in the context of U.S. militarism on the islands and how another sacred space—the Hawaiian island of Kahoolawe—was turned into a bombing range by the U.S. during World War II. In a piece titled “Mauna Kea Is Our Modern-Day Kahoolawe,” Watson wrote, “The movement to protect Mauna Kea has nothing to do with a telescope. It has everything to do with the enduring battle over Hawaii’s future.”

The issue is so important, Hawaiian elders—or “kupuna,” as they are called—situated themselves on the front lines of the Mauna Kea blockade. In mid-July, about 30 kupuna were arrested, and some had to be carried to police vans. It was a public relations nightmare for the TMT and the state of Hawaii. The protesters are calling themselves “protectors” just as native American movements like the Standing Rock Sioux did in their resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Indeed, representatives of the Standing Rock Sioux have visited the Hawaiian-led blockade of the TMT project to lend their solidarity. First Nations chiefs in Canada have asked their government to pull funding from the TMT in support of their indigenous Hawaiian brothers and sisters. Celebrities like the actor Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson and musician Jack Johnson have traveled to the blockade to show their support. “Game of Thrones” actor Jason Momoa has been a proud supporter of the movement for years, coining the term “We Are Mauna Kea.” Even scientists are beginning to speak out under the hashtag #ScientistsforMaunaKea.

There has been a worldwide movement of indigenous peoples over the past several decades challenging the occupations of their lands at the United Nations and joining with one another in solidarity to assert their stewardship of the land, air and water. The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was adopted by the majority of member nations at the General Assembly, with the exception of the United States and several other nations. Pisciotta and other indigenous Hawaiians participated in the U.N. talks that led to the declaration and helped to draft the language of UNDRIP. She explained that the broader framework to understand the battle over Mauna Kea is “our right to self-determination as defined by international law.”

Despite Ige’s revocation of the proclamation to allow construction of the TMT to start immediately, the battle is not over. He extended the time frame for the TMT construction to begin by two years, indicating he may be hoping to wait out the activists. But the fight has now moved out of the courts and into the streets, where Hawaiians enjoy broad support for their opposition to the project. The state of Hawaii, the corporations and governments that are invested in the project, and the astronomy community all have to contend with being on the wrong side of a moral struggle as they decide whether to trample on the rights of indigenous peoples.

Watch Sonali Kolhatkar’s interview with Kealoha Pisciotta on “Rising Up With Sonali”:

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.