Saving the Vaquita Porpoise

A Sea Shepherd team makes a last-ditch effort to ensure survival of critically endangered marine mammals in the Sea of Cortez. The Sea Shepherd crew hauls up a ghost net filled with dead marine life. (Veronique Vial)

The Sea Shepherd crew hauls up a ghost net filled with dead marine life. (Veronique Vial)

Crossing the border into Mexicali is like entering a mosh pit of battered vehicles. There are no lanes, no order, drivers seem to merge on faith. My friend Vero and I are searching for an address to pick up something that we are to deliver to the crew of Sea Shepherd, the notorious defenders of the world’s oceans. But our GPS is not up to speed; it’s only telling us where to go after we’ve passed our turnoff. A man pushing a food cart motions for me to back up—I’m going down a one-way street the wrong way!

After much circling, reversing and dropped phone calls, someone’s tio nods at us, then scans the sidewalk before slipping us a sealed envelope. We speed off down Highway 5 to San Felipe.

We drive through miles and miles of Baja California’s barren desert, bordered by plains of white salt flats, a remnant of when the Colorado River used to flow into the Gulf of California. Back then, it was a lush wetland, but in 1963, the U.S. stopped the flow with the Glen Canyon Dam. That was a big upset to the marine habitat, although not the biggest one.

The indigenous people of this area, the Cocopah, fished and lived sustainably for 3,000 years, but by the 1920s they were teetering on extinction from the ravages of war and disease. Around that time, Mexican laborers were venturing north in pursuit of the mighty totoaba drum fish, specifically it’s buche, a gas-filled swim bladder that regulates a fish’s buoyancy. There was a big Chinese market for that little organ—fish maw soup is made from it. Like other endangered species’ parts, such as rhino horn, shark fins and tiger testicles, the Chinese believe the totoaba maw has curative powers. But scientists and environmentalists call bullshit.

In 1940, fishermen accelerated their productivity by abandoning hook and line methods and implementing gill nets. The incidental capture—the “bycatch”—in these nets included rays, sharks, sea turtles, birds, corals and a certain cetacean local fishermen called vaquita, meaning “little cow.” I didn’t get a clear explanation on why it’s called that, but it is Mexico’s national marine animal and the most endangered sea mammal on earth. Not until 1958 did biologists officially recognize it as a species, endemic to the upper gulf. Vaquita have been around for 3.5 million years, but with the advent of gill nets, their numbers began declining at an alarming rate.

By 1975, the totoaba fishery was collapsing, so the Mexican government shut it down. Still, people kept on fishing. In 1986, the totoaba was listed as endangered, and in 1996, critically endangered. At that time, the first survey ever done revealed there were only 567 vaquita porpoises in existence. The vaquita is a shy little creature, not flashy like a dolphin. They don’t jump and play, so they are rarely seen. In fact, some people even deny their existence. When vaquita corpses are found, it’s always because they struggled and drowned in gill nets. In 1990, vaquita were listed as endangered, yet in 1991, 128 dead vaquita were pulled out of gill nets. They never survive that entanglement.

In 1993, a biosphere was established where the majority of vaquita have been sighted. Gill nets with a 10-inch or larger mesh were banned, but there was no serious enforcement. Laws don’t hold much power over the people’s will in this part of the world. The refuge is near San Felipe, a poor fishing village. What are they supposed to do? By 2008 the vaquita population had dropped to 245.

*****

On the outskirts of San Felipe, we whiz by a gated community called El Dorado Ranch—a benign haven for ex-pats drawn to cheap and sunny Mexico. But crime has diminished their quality of life and the value of their homes. I read that they are short on security guards because not enough locals can pass the drug tests.

San Felipe sits close to the top of the Gulf of California, also known as the Sea of Cortez. We pass burnt-out houses, junked cars in garbage-strewn lots, abandoned buildings and barbed wire barricades around concrete fences spiked with broken glass. The village center has beautiful bones, but the flesh is scorched and malnourished. On the surface, it seems like it wouldn’t take much to restore it to a wonderful seaside idyll, but there are big, systemic problems here.

The totoaba buche is referred to as the “cocaine of the sea,” and, like that drug, it has a serious criminal underbelly. In 2012, the Sinaloan cartel ramped up operations in the gulf. Because it is illicit, the buche’s price has skyrocketed, fetching up to $100,000 in China. The cartel was paying poachers—bucheros—anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000 per bladder, a hell of a lot of money considering that one haul could bring in dozens of totoaba.

We arrive at our motel, grateful that there is an all-night security guard. The last time Vero was in town, she kept finding the tires on her car punctured. She warns me to be low-key and not talk too loudly about why we’re here. You can’t be sure where people’s allegiances lie. Sea Shepherd arrived in 2015 to patrol the vaquita refuge area, and the crew spends most of its time hauling up illegal gill nets and freeing any marine life that might still be alive. If crew members find a dead totoaba, they slice up the buche so it can’t be sold. Then they destroy the nets, which cost fishermen $3,000 apiece. Sea Shepherd’s confrontational methods have garnered some hostility in these parts. Shit happens on the frontline.

*****

In 2015, bending to pressure from conservationists, then-President Enrique Peña Nieto’s government started paying fishermen to switch their gear to “safer” gill nets and keep outside of the refuge. Some took a lump sum to get out of fishing altogether and started other businesses, with varying degrees of success. It was a windfall to those who were good at playing the system; others, not so much. Fishermen who work for owners of small, motorized boats called pangas were not compensated directly. Instead, their share often went to family members of the panga owners. Some fishermen received as little as $200 a month, while a handful of them were able to haul in up to $100,000 a month. And the poaching continues.

Many poachers conceal their totoaba nets with weights below the surface of the water and fish under the cover of night. This is a dangerous practice that has led to many mishaps and several drownings.

*****

At the crack of dawn the next day, we make our way to the marina where the White Holly is docked. This 1944 U.S. Coast Guard cutter once served in Pearl Harbor and now flies Sea Shepherd’s skull-and-crossbones flag. It is one of the 12 ships in Sea Shepherd’s international fleet. The secret envelope that we intercepted back in Mexicali contains the key to a panga used for commuting back and forth to the White Holly when she’s anchored at sea.

When Vero was on the Sea Shepherd in February, the crew had to turn high-powered water hoses on angry fishermen who were throwing Molotov cocktails and trying to climb aboard to sabotage their equipment. Totoaba season is over, so there shouldn’t be any fireworks, but the crew has two Mexican marines and two federal police officers on board just in case.

Jack, the drone operator, says, “Today we’re just glorified garbagemen, picking up trash and hauling out ghost nets”—these are defunct nets that have broken loose or been abandoned but still threaten marine life. Jack is a charismatic 22-year-old who sports a mohawk and multiple tattoos. He tells me about the dead vaquita he found two months ago in a ghost net. “I can’t get the smell out of my shoes,” he says. It’s not surprising to learn that he’s from Northern Ireland: He’s used to conflict and has a take-no-prisoners attitude. He points out the 5- by 10-mile vaquita refuge on the radar. “This is where we get shot at; all the madness happens here.” Jack is featured in the Leonardo DiCaprio-produced documentary thriller, “Sea of Shadows,” which traces the black-market trail of the totoaba buche to China.

The only American on board—and the only person who has no visible tattoos—is Capt. Shannon, a member of the U.S. Coast Guard who gained his sea time working on luxury yachts. He’s a quiet man who seems to be most comfortable gazing over the sea’s horizon.

Per-Erik is the chief engineer. He and Shannon are the only paid crew members. He’s a tall, strong Swede who’s sailed many seas. When he’s not on the water, he splits his time between Sweden, where his seven children live, and Cuba. He reminds me a little of my dad, a salty dog with a million stories. He navigates the ship with an easy grace, occasionally barking out orders to the less experienced engineers.

The first mate, Blair, is a fit and trim practitioner of yoga who hails from Melbourne. He points out a little black blur on the radar screen—a ghost net. That will be the day’s catch.

A panga comes up starboard; one of the fishermen flips us the bird. Vero aims her camera and he pulls his hoodie over his face as the boat zooms off.

The rest of the crew consists of a cross section of dedicated volunteers. Elven, the media director, is in charge of producing the web series for Sea Shepherd’s “Milagro 5” campaign. Each of the five years they’ve been in the gulf has been a Milagro campaign. Elven is a cinematographer who gave up lucrative jobs to join this crew. “I’ve done many things I won’t put my name on,” he says, “but this I’m proud of.” His mother introduced him to Sea Shepherd. “You plant a seed and it grows.”

Like him, his assistant, Nina, is French. She tells me her family are travelers—her mother was born in the Congo and her grandfather lives in La Paz, Mexico. He always told her, “There is no worse fight than the one you don’t do.”

Richie grew up in a working-class family in Mexico City. Though his parents would have preferred he be a lawyer, they supported his studies in hydrobiology and his work with Sea Shepherd. He feels more indigenous than Spanish, because he strives to be in harmony with the earth. The normalization of corruption and the violence in his country are a source of shame and suffering for him. “People are exploited and have no options” he laments. He hopes to work with his fellow Mexicans to create, empathy, solidarity and respect. “I am a citizen of the world first, then a citizen of Mexico,” he says.

Lucas, the chef, is a fresh-faced Belgian who I guess to be in his 20s; turns out he’s 40. He became passionate about Sea Shepherd from watching “Whale Wars” and studied vegan cooking to gain entrance. Not everyone on board is strictly vegan, but they are when on the ship. Lucas believes the way to change the world is through diet. He doesn’t care if he’s paid or not. He says he is “paying his rent to the world.”

This is a sentiment shared by most of the crew. We are overfishing our oceans, and fisheries are in collapse in every part of the world. On the Sea Shepherd, limited food options and humble accommodations are not seen as a sacrifice, but as a righteous way to live.

Back on land, we go to a recommended restaurant. A baseball game is playing on several screens. A sun-withered American couple in flip-flops drink margaritas and argue out loud. We guiltily order fish tacos because nothing else on the menu appeals. It’s hard to give up old habits.

The next day is a placid one on board the ship, the highlight being the retrieval of a wayward birthday balloon. Nonetheless, the crew is hard at work, swabbing the deck, cutting up ghost nets, removing hooks and weights. Some of the booty gets recycled into Sea Shepherd bracelets and an upcoming line of sneakers—making a small dent in the mass of fishing gear that makes up half of the plastic that clogs the world’s oceans.

*****

Carolina is the chief of operations and the one everyone refers to as “the boss.” She is distressed. There is concern that the number of vaquita might have dropped to below six. If that is the case, this sweet little snub-nosed creature with coal black markings under its eyes might never recover.

While Sea Shepherd is the vaquitas’ only protector, the ship casts a big shadow, literally and figuratively. It repels their predators, but it also must disturb the vaquitas. In a few weeks, fishing season will end and the upper gulf will not be plagued with nets. The campaign will take a break, and hopefully the calm will encourage some porpoises to hook up and make babies.

Sunshine Rodriguez, former leader of the local fishermen’s federation, would be happy to see the vaquita vanish. He blames the state of his community on the gill-netting ban and thinks the vaquitas’ demise is due to the loss of its breeding habitat in the wake of the diversion of the Colorado River. If the vaquita were finally gone, fishermen could go back to their old ways. But gill-netting is a hazard to all marine life in the Sea of Cortez. What Jacques Cousteau called “the aquarium of the world” is in dire peril.

Javier is a fisherman who has accepted that the old ways are unsustainable. He created a chango, a shrimp trawling net with safety features that prevents bycatch but, unfortunately, reduces the catch significantly. He took a lump sum to get out of the fishing business and is dedicated to finding alternative methods of fishing. But he gets no support from the government. Fishermen who use alternative gear have been shunned, maligned and intimidated. They have endured threats, burnt-up trucks, angry mobs in the night and fights at sea. In March, the government discontinued its compensation program, sparking a riot in San Felipe. The cartel exploited the fishermen’s desperation, slashing what it pays for a buche, while the price in China only goes up.

We are sitting on the beach, waiting to hear from Javier, who is traveling from La Paz, where he’s been at a Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species conference. A mild breeze coming off the ocean makes the hot sun intoxicating. We lie back and try to luxuriate, in spite of the mounds of garbage along the tide line. But every few minutes, needy peddlers solicit us with their wares.

Javier’s son texts to say that Javier is tired and all talked out.

A toddler is chasing seagulls. His glee is infectious, and we laugh with his family, which is picnicking beside us. A mariachi band has started playing, and suddenly people are streaming down the malecón. The smell of grilled meat and sweet corn tortillas fills the air. Such a good life, if only the people could solve the fundamental problem their community faces.

Dr. Pablo Chee Rodriguez believes the solution is compromise. On our return from San Felipe, we stop by his hospital in Mexicali. He has a warm and humble demeanor, and is eager to share his ideas. “Compromise is conservation,” he says. His Chinese ancestors came to Mexico in 1905 as merchants. Though trained as an anesthesiologist, he is primarily a businessman, who founded this hospital and another here. He recently saved the life of a poacher who had been shot in the head while trying to flee with a totoaba. His hospital just co-sponsored a hook-and-line fishing tournament in San Felipe to attract tourists. All the proceeds went toward an aquaponic facility that is training locals how to raise fish for release into the wild. He wants to make the tournament an annual event. He wants to put totoaba on the menu of restaurants and private homes. He wants to create a trust for the fishermen of San Felipe. He wants to starve out the Mexican cartel and the Chinese mafia.

In an attempt to ease tensions and discuss options, he has brought together the poachers and the ocean defenders, but even if they find common ground, navigating the systemic corruption in Mexico is overwhelming. Nevertheless, he has made it his mission to bring health and prosperity to San Felipe.

Some scoff at his promotion of aquaculture. It takes seven years for totoaba to reach maturity, and the presence of hatchery fish will not only increase the craze for wild totoaba, but weaken the fish stocks. In the meantime, the vaquitas’ fate hangs in the balance.

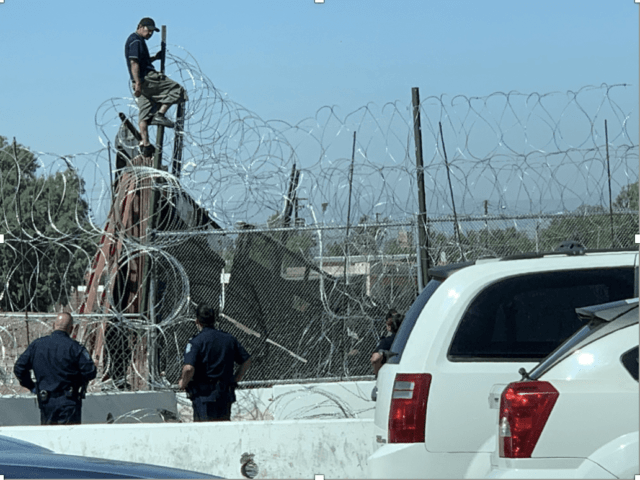

On our approach to the border, there is a man straddling the top of the barbed wire fence that divides Mexico and the U.S. He gazes down sadly at the officials on either side, weighing his options. Like all the characters we met this week, he knows what he wants. He just can’t see a way to get it.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.