Evolution of a Medium

Emily Nussbaum began writing her New Yorker TV column in 2011, and her Pulitzer-winning career parallels television's ascent. "Louie" star Louie C.K. and co-star Pamela Adlon appear in Nussbaum's book, as well as in this still from the now-canceled "Louie." (FX)

"Louie" star Louie C.K. and co-star Pamela Adlon appear in Nussbaum's book, as well as in this still from the now-canceled "Louie." (FX)

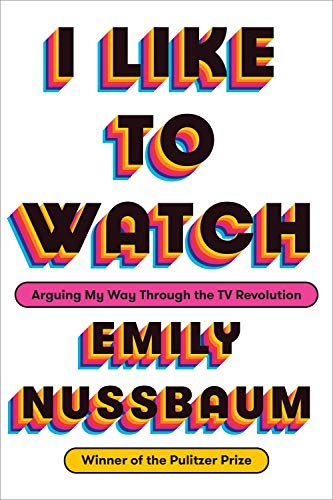

“I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution”

A book by Emily Nussbaum

Emily Nussbaum began writing her New Yorker TV column in 2011, surfing the medium’s Great Transformation. Ten years ago, nobody streamed; today, fewer and fewer watch “live” television. In 2007, Netflix shipped its billionth DVD mailer, propping up the U.S. Postal Service; today its streaming proves harder to resist than even Amazon Prime. Like Netflix, Prime’s brand now routinely pumps out original shows and movies. Oscar sweeps appear imminent.

By 2014, Ferguson’s street protests, police brutality, and sexual harassment scandals took center stage in both life and drama. Bingeing and anthology series like “Black Mirror” turned into mainstream memes, as TV material, once a focal point of family life, now seeded a cloud-storm of visual storytelling across laptops, mobile phones, and high-density wide screens. In her first collection, “I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution,” Nussbaum, acutely aware of all these forces, describes how they bashed up against one another in show after show, even as they compressed history and replaced time’s gravity with an avalanche of content. (Remember “appointment viewing”?) With her 2016 Pulitzer Prize, she thrives as a pivotal contemporary voice; her calm reasoning and light-saber resolve make you cheer for criticism itself. Her career parallels television’s ascent.

Click here to read long excerpts from “I Like to Watch” at Google Books.

When Nussbaum abandoned her graduate degree in literature, the medium still had a junky afterglow. “TV might be a gold mine economically speaking,” she writes in the opening piece, “How Buffy the Vampire Slayer Turned Me Into a TV Critic,” “but that only made it more corrupt. If you were an artist, writing TV was selling out; if you were an intellectual, watching it was a sordid pleasure, like chain-smoking. People still referred to television, with no irony, as ‘the boob tube’ and ‘the idiot box.’ (Some people still do.)” But then “Buffy,” “The Larry Sanders Show,” “Twin Peaks,” and “The X Files” started fiddling with these assumptions.

When she wrote about “The Sopranos” back in 2007 for New York magazine, these shifts had become a new subject: how the suddenly moribund networks couldn’t contain the cinematic ambition or sheer production scale of viewer demand. “Bingeing” now describes both a form of grazing and a crude metaphor for endless consumption that reduces viewers to playing a constant game of catch-up. Shrewdly, and with glaring efficiency, Nussbaum details how product placement now supplants old-fashioned “ads,” and viewers found their responses, desires and impulses recorded and monetized with every twitch of social media.

Many of Nussbaum’s insights achieve rapid focus, like how producer Shonda Rhimes’ “Scandal” far out-juiced “House of Cards.” She calls “Scandal” “a series that’s soapy rather than noirish but much more fun, and that, in its lunatic way, may have more to say about Washington ambition.” Yes! Now more thought-bombs on “Brainwashed,” “West Wing’s” infinite loop, and the sturdy Danish political drama, “Borgen,” please. She wins you over early on by calling Aaron Sorkin a “utopian solipsist,” and threads white-hot ideas inside cleverly disguised asides—“Vanderpump Rules” sports a rich meta-moxie: “…It’s a reality show about the types of people who are most likely to agree to appear on a reality show.” She honors the sly wit of “BoJack Horseman” (“Diane, the whole point of television is it’s a collaborative medium where one person gets all the credit”), and dunks “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” with a single stroke: “In The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, sexism exists. But it never gets inside Midge. Her marvelousness comes from the fact that she’s immune, a self-adoring alpha whose routines feel like feminist TED talks, with some ‘fucks. ’”

With great flourish and daring, she opens her 2007 “Sopranos” essay like this: “David Chase, you sadist. We trusted you, and then you turned on us—and maybe we deserved it.” So many devoured this show and its self-congratulatory airs that a fair-minded assessment rings almost radical. In “The Long Con,” Nussbaum draws attention to how Chase’s material seemed like an overdue yet entirely plausible offspring of its frame: “Chase was the first TV creator to truly take advantage, in every sense, of the odd bond a series has with its audience: an intimate dynamic that builds over time, like any therapeutic relationship.” Her praise deftly sidesteps hype: Tony Soprano, played with elephantine poise by James Gandolfini as a “hurting bad boy,” travels from sympathetic villain to abject monster; he’s playing his “please like me” shtick straight at us, just like he’s playing his therapist and wife. His all too believable nemesis/mother, Livia, played “a villain who crushed her enemies with the illusion of powerlessness.”

Nussbaum carefully teases out how the show entranced viewers, why it still bathes in a foundational afterglow alongside “Breaking Bad.” While she adores the character Tony Soprano, she finds the ending of the piece, with his larger fraud, to be a slap in the face for believing in the whole lovable mobster conceit. Instead of Chase falling in love with his protagonist on cue, it’s as though he regrets his whole Frankensteinian enterprise. (A fade to black, remember, can convey both infinity and doom. Listen to that suicidal Springsteen “Nebraska” outtake.)

In this compilation’s bravura centerpiece, “Confessions of the Human Shield,” Nussbaum traces the Harvey Weinstein scandal back through Roman Polanksi, Miles Davis, Woody Allen, Bill Cosby, and John Updike. Louis CK’s standup and “Louie” dominated the new TV, a breakout figure who self-destructed with the same untidy defiance that once brought him acclaim (“making a mess is what men get to do…”). Perversely, just as this writerly comic faced public repudiation, he sponsored a clutch of female iconoclasts, among them Tig Notaro (“One Mississippi”), and Pamela Adlon, his co-star on “Louie,” with whom he’d co-created “Better Things.” In fact, Nussbaum adds, “his show became a catalyst for a wave of autobiographical comedies, many by women, made by creators who were fascinated, just as he was, by sexual compulsion and shame, forgiveness and blame.” The new TV tossed up implacable conundrums: How to square a misogynist jerk with how he backed indispensable feminist and LGBTQ views?

In retrospect, Nussbaum notes, “Louie” “seems like an extended anxiety dream about what might happen if women turned the tables.” That catches how TV’s hot flashes of the past decade have recentered comedy, drama, scandal, politics, and our general conflation of Reality TV with “reality.” Now she faces the same Herculean task as many of her subjects: how to top herself.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.