U.N. Report Condemns Torture of Assange

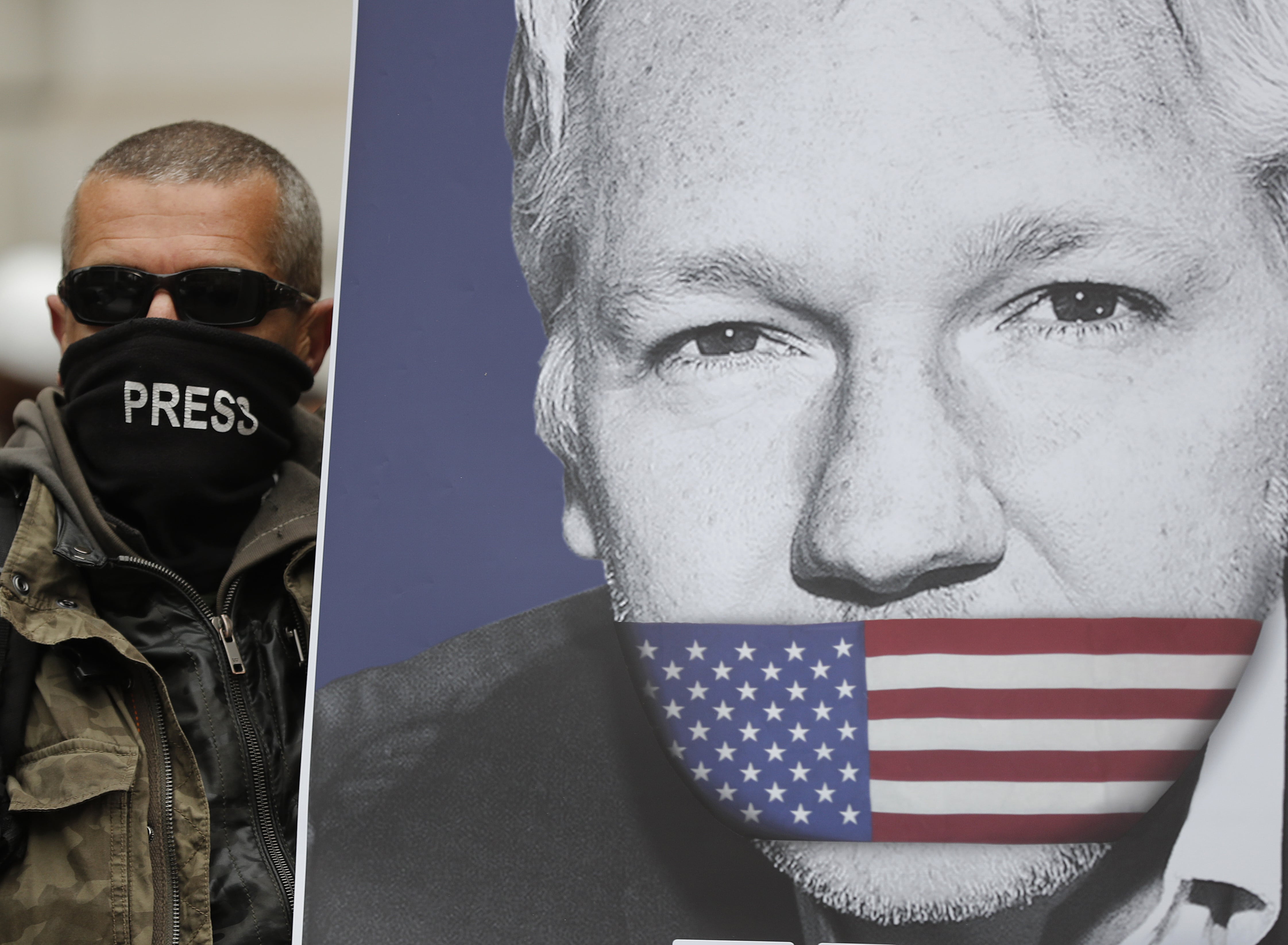

A U.N. expert finds the WikiLeaks founder has been subjected to psychological torture—and media around the globe played a part. Frank Augstein / AP

Frank Augstein / AP

Listen to Scheer and Melzer discuss the details of Julian Assange’s torture and how several Western democracies, widely-circulated and reputable publications, and even many average people have contributed to the mobbing and dehumanization of the WikiLeaks founder. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

—Introduction by Natasha Hakimi Zapata

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence,” where the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, Nils Melzer, a brilliant human rights attorney. And I will let him talk a little bit about his own credentials. But in some ways this is one of the most important interviews that I’ve ever done. And let me explain that. We’re talking about the case of Julian Assange. And I went to a Los Angeles Press Association meeting last night; his name didn’t get mentioned. Chelsea Manning’s name doesn’t get mentioned. And this was a gathering of the elite of the Los Angeles press corps, but it’s true nationally. And Nils Melzer is somebody who has devoted most of his adult life to considering questions of human rights. He worked for the Red Cross for over a decade, he’s the U.N. Special Rapporteur on this; I’ll let him define that obligation. He’s written very important books on warfare, drone warfare; he’s written guides for NATO. And so why don’t you explain how you came to write this report? And what I found so devastating about it is you say over and over–particularly in an article that I’m going to list on the site and talk about, “Demasking the Torture of Julian Assange.” You were a skeptic–a deep skeptic, actually–about his case. Were you not?

Nils Melzer: Yes, ah–thanks, Bob, for having me on the program. And yes, indeed, I actually, I was approached in last December, that’s December 2018, by Assange’s lawyers requesting the protection of my U.N. mandate. And I’m the Special Rapporteur on torture, so I can examine, you know, the compliance of states with the prohibition of torture. And I was very skeptical, because I’d never met Assange before; I had never really dealt with his case before. And so I didn’t really know much about him. But I had somehow absorbed over the years all these little snippets of information that had been shared in the press of him being a suspected rapist, of him being a hacker, of him being a Russian spy, of him being a narcissist, you know, so–an ungrateful person, a mean person. So I had this kind of pre-programmed image in my mind. And so the first thought I had when his lawyers contacted me, I thought oh yeah, here he comes, and now he’s going to claim he’s being tortured.

But basically, I didn’t take it seriously. And it took a second attempt to kind of shake me a little bit and say, you need to look at this, you know. And so once I opened the book, basically, and started looking at the actual evidence and facts for all these nametags that are being circulated in the press, I was shocked to see that there was very little substance that actually supported these qualifications. And so that’s why I then also got intrigued, and I said well, I have to look into this more deeply. And the deeper I got into the facts, the more I realized that there was a very thin evidence basis for these assumptions.

RS: You know, let me say, I’ve been a skeptic of the government. I generally side with whistleblowers, and I remember in the famous case of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, I happened to be involved in that trial a little bit as a defense expert witness on Vietnam, that I had written about. And they really went out of their way to smear Ellsberg, the government did. And in fact, the whole Watergate controversy was over–really began with an effort to–well, a break-in at Daniel Ellsberg’s psychoanalyst’s office, and to get incriminating documents and evidence about his personal life, in a way to smear him. Now Ellsberg is remembered as this, you know, generally virtuous person who was vindicated. But then when I was following the–this case, with Julian Assange, as with most people, we think we’re on guard against distortion. But until I read your article, I didn’t realize how grotesque this case is. And I was thinking of the Dreyfus affair. And I read your article, which I guess is self-published–we’ll get into that, why other publications haven’t picked up on this. But to my mind, it was like Emile Zola in J’Accuse…!, in the Alfred Dreyfus case 120 years ago. Again, a man accused of espionage. And I think of your document, “Demasking the Torture of Julian Assange,” reads like Zola’s document; it’s a J’Accuse…!. And I’d like to take you through five essential points of your article, and of the U.N. report that was released in summarizing this. The first one concerns the whole reason why Julian Assange was holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy, was the charge, ostensibly developed in Sweden, that he had raped two women. And it seems to me on that first point–which I really have not read anywhere else as clearly as this–not only do the two women who have accused, or claimed to have accused, now say the police, zealous Swedish police railroaded it. But you actually say in both cases the issue has nothing to do with rape, and it has to do with whether you used a defective condom. Which in Sweden, I guess, amounts to rape, but nowhere else in the world. Am I oversimplifying this?

NM: Yeah, maybe slightly. I mean, I think–I think it’s very important not to misunderstand my piece as somehow saying rape allegations should not be taken seriously. They should. They should. I mean, rape is a serious crime, and whenever a woman makes a credible allegation, it needs to be investigated. So there is no question about that. Because I think too many women in history have suffered from, you know, the opposite view of not being taken seriously. So I’m not saying that. What I’m saying here is that two women have made allegations at the police. Now, it’s important to know–and we know that from the police reports–they did not go to the police to [complain] about Assange and to make a, to report a crime. But one of them feared that she had, you know, might have been infected with HIV or, you know, another STD, and she wanted Assange to take a test. And because he was reluctant–he said well, I’ve just done one three months ago, I don’t need to do one again–she went to the police and asked the other woman to accompany her, and she wanted to ask the police whether she could force Assange to take a test. She did not want to go to claim she had been raped. But the police listened to her story and said, well, we’re going to register this as a complaint of rape.

And then she said, no, I didn’t want to complain about rape; I wanted him to take a test. And they said well, yeah, but we are going to register this as rape, because this is an ex officio offense; this means it’s an offense that we have to prosecute whether, you know, the complainant wants to or not. And then she refused to sign and was so distraught that she had to go home, she had to suspend the questioning. So it’s very important to know that I’m not discrediting the women–women who wanted to report a crime. I’m discrediting a Swedish prosecution that was initiated by the Swedish officials, and that interpreted facts brought to their knowledge the way they wanted to see them. So that’s the first point that’s very important. I’m really confronting the authorities for how they dealt with this case, and that they–in my view, everything points to the interpretation that the authorities tried zealously to find something, you know, that would support a rape allegation. So that’s a very important first point. The second thing is, ah, that the evidence that was then submitted in support of the allegations of rape made by the Swedish police, just does not support these allegations. It, it’s–it’s a condom that was ripped. So one woman said that she had had consensual intercourse with Assange, and that he intentionally ripped a condom during that intercourse. Now, he says no, that that’s not true. Then she submits a condom as evidence, but the condom does not show any DNA at all. Not his, and not hers. And that’s forensically not possible if it has been used. So that looks more like a planted piece of evidence that would actually point to a false accusation, which would have to be investigated as a separate crime. The other woman claimed that–well, she had had intercourse several times, protected with a condom, with Mr. Assange, in the same night. And in the morning when she was half asleep, he basically had intercourse with her without a condom. And during that intercourse she asked him, do you wear a condom, he said no. And then she reported that she was just, you know, too tired of insisting on a condom and she let him continue. But that does not sound like someone who’s not consenting, which you would need for the allegation of rape. Right? You can say that’s perhaps a nuisance, that he tried to do this. But if she doesn’t–she has to somehow express that she doesn’t consent for this to be, or it has to be implicitly clear to Assange that she doesn’t consent for this to be rape. This was not the case, according to her own allegations in the police report. So that’s why the–what I’m criticizing is that we have a Swedish prosecution that insists on accusing Assange for rape–or you know, investigating rape against him and disseminating a narrative of rape suspects–without it actually being covered by the allegations that were recorded in the police report. The second woman even explicitly said on Twitter in April 2013, no, I have not been raped. And that’s the one that submitted the condom without any DNA on it. So there’s plenty of points where the prosecution would have had all reasons to tone down its approach, and you know, investigate, well, where’s the evidence. But instead they went, very early on they went public with these allegations; but then they didn’t investigate it thoroughly. And so they maintained this kind of narrative for years and years, which obviously strongly undermined the credibility of Assange.

RS: Well, just to summarize, now, that first point. You were a skeptic; you, as you have written, and were inclined to think, you know, that this Assange is guilty, or possibly guilty, of this charge. And then this investigation, as the UN Rapporteur, you come to a different conclusion. Let’s take the second point. The second one is you say, all right, the first part doesn’t hold up. But:

I thought, but surely Assange must be a hacker! But what I found is that all his disclosures had been freely leaked to him, and that no one accuses him of having hacked a single computer. In fact, the only arguable hacking charge against him relates to his alleged unsuccessful attempt to help breaking a password which, had it been successful, might have helped his source to cover her tracks. In short: a rather isolated, speculative, and inconsequential chain of events; a bit like trying to prosecute a driver who unsuccessfully attempted to exceed the speed limit, but failed because their car was too weak.

That’s what the hacking charge is all about?

NM: Yes. Well, I–you know, I started out from the premise that this must be a professional hacker. So he–you know, I didn’t know anything about WikiLeaks; shame on me, but I didn’t. I just hadn’t dealt with it so far. And I found out that actually, he’s not being alleged to have, you know–let’s say, stolen any information through hacking. He has received all his information that he disclosed–these monumental leaks–he received all that information from people, whistleblowers, who had full authorized access within their organizations, just as Bradley or Chelsea Manning. Allegedly, he tried to help her–Chelsea–to decode a password of a colleague so she could log in with a different name so she could cover her tracks. But it didn’t succeed. So again, I–you know, he might be guilty of having done that, or having attempted that. But now that’s a crime where the maximum penalty is five years, and the maximum penalty obviously only applies if you succeed, and you cause substantial harm and so on; otherwise it will not be the maximum penalty. If you attempt unsuccessfully, and there is no harm resulting from that attempt–not from the disclosures, which in my opinion were lawful under international law, but from the attempt–no harm resulted. So no serious imprisonment, you know, prison sentence could be imposed for that. Now, so I don’t think it would be realistic to assume that Assange would go to the U.S., you know, that the court of the Eastern district of Virginia would say, oh yeah, well you attempted to decode a password but you didn’t succeed so we’ll give you six weeks of prison time and then you’ll be free to go home. I don’t think that’s a realistic assumption. If you look at the 17 other charges that have been added, they all refer to obtaining and publishing–not for stealing–but obtaining and publishing secret information. Now, that’s what investigative journalists do every day, everywhere in the world, from BBC to New York Times, and Washington Post and The Guardian, and ABC News in Australia. That’s just the normal, you know, work of journalists; they receive secret information, they look through it; is it of public interest, if they think it is, they will publish it. And that’s not–that’s protected by freedom of speech and freedom of press. But the 17 charges that are now being, obviously, promoted under the Espionage Act against Assange, they all refer to these types of activities. So the only hacking charge is this unsuccessful attempt which could not give him more than a couple of weeks’ imprisonment in my honest opinion. And I don’t think that that is a realistic prospect; I think it is realistic to expect that they will press for maximum penalties and try to somehow establish a precedent where they can qualify publishing of secret national security information as espionage, even though the publisher is not an American, didn’t do it in America, and received the information, without stealing it, mainly from the authorized source.

RS: Yeah, the hacking thing was important. Because otherwise Julian Assange is in the same position as the Washington Post or the New York Times were when they printed the Pentagon Papers. He’s a publisher. And they can all jump up and down–and as I say, I hang out, I worked for the LA Times for 29 years, and I know mainstream journalism, and they can twist and turn in the wind. But the fact of the matter is, Julian Assange loses this case, there is, as you suggest at the end of your column, there are very grim prospects for freedom of the press. Because up until now, the publishers have been protected by the U.S. Constitution, by decisions of the court, far and wide internationally. And so the way to make Julian Assange be something other than a publisher, you have to show him being actively involved in obtaining the secrets. Now of course, journalists are very aggressive in obtaining information they think the public has a right to know. But in this case, what they’re trying to do is blur the distinction between Chelsea Manning and Assange. Now unfortunately, the way they’re going to do that, it seems to me, is trying to destroy Chelsea Manning. Everybody that I know seems to have forgotten that she is–correct me if I’m wrong–as we’re speaking, still in jail, right?

NM: As far as I know, that’s the case, yes. I cannot [inaudible] but yes, as far as I know she’s [inaudible] for civil contempt of the court.

RS: Yes, of–in grand jury proceedings. And so here you have–now, Chelsea Manning, just for people who don’t follow the intricacies, she is in the position that Daniel Ellsberg was in. Daniel Ellsberg had security clearances, much higher than Chelsea Manning. He released information, the Pentagon history of the Vietnam War, which contained much higher level classified information than Chelsea Manning. But Chelsea Manning’s information was very damaging, because it showed U.S. troops firing on innocent civilians and journalists. And as you point out in your column, a great deal of information–well, let me read what you wrote. “But all I found”–I looked into this–this gets to point three: “Well then, I thought, at least we know for sure that Assange is a Russian spy, has interfered with US elections, and negligently caused people’s deaths!” Right? That’s you writing that, that you believed that.

NM: Right.

RS: Right?

NM: I believed that, yes.

RS: Yes. I’m sure most people believe that in the United States; they’ve been told this over and over again. But then you write: “But all I found is that he consistently published true information of inherent public interest without any breach of trust, duty or allegiance.” So that goes to this question: he didn’t have an oath to the U.S. government; he was not given these secrets to preserve that oath and guard it. He was in the position of the New York Times or the Washington Post, getting the Pentagon Papers from Daniel Ellsberg. And you say: “Yes, he exposed war crimes, corruption and abuse, but let’s not confuse national security with governmental impunity.” And what is so shocking is that in the United States now, there are very few publishers and very few political people speaking out in defense of Julian Assange’s right to publish material and make it available to the Washington Post, to the Guardian, to other mainstream journalists. Is that not true?

NM: That is–that is a huge concern. And you know–well, you’ve just recently had the story of the New York Times submitting its own articles to the U.S. government for clearance. I mean, you certainly have noted that as well. And so that’s really, really worrying. We’ve had the raids on ABC News in Australia by the Australian federal police in relation to leaks of secret Australian government information that also showed evidence of abusive killing of civilians by Australian special forces in Afghanistan. So they raided the ABC News headquarters to find, you know, the sources and more information about that. So that is a really worrying development.

RS: So let’s understand–I’m talking to Nils Melzer, who is the human rights, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. And I dare say–and you have a long history, decades, of looking into these kinds of issues for the Red Cross, for the UN, for NATO, for others. And your prejudice–and I suspect that it’s true of most well-intentioned people throughout what is called the West–is that, OK, this happens in totalitarian countries. But we have restraints; we have checks and balances in what used to be called the free world. And what’s happening here is you’re describing, you know–and it’s interesting to see the UN taking a consistent position, so it’s not just Saudi Arabia or China or so forth that you go after, but you have to raise questions throughout the world. And you know, here, this is an example where we’re saying inconvenient truth–to use Al Gore’s old phrase–inconvenient news, that’s inconvenient to a government, if it happens to call itself a democracy like the United States or England–then they can shoot the messenger. That’s really what we’re talking about. The crime of Julian Assange as you have written it, was not that he distorted the American election in some kind of way that compromises democracy, but rather, he might have informed the American electorate. He might have brought up inconvenient truth. Right? Because after all, in the WikiLeaks exposure there was what the Democratic National Committee had done to undermine Bernie Sanders’ campaign; there was the account of Hillary Clinton’s speeches to Goldman Sachs, which undermined her claim to be of a populist bent. And so it was inconvenient information that was released. And yet, clearly, that’s what the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects.

NM: You know, democratic elections in my country, in Switzerland, and certainly also in the U.S.–and the nature of this is that you have an election campaign during which the candidates are exposed to increased scrutiny. So they have to expect that some journalist digs out, you know, true information that may be inconvenient to them, and will even time it very inconveniently. Journalists are not obliged to be impartial in elections. They just have–well, in my view at least, they should be true; so the information they publish should be true. And the one thing that you cannot claim of WikiLeaks is that they ever published fake news; they don’t. They don’t interpret the news; they simply publish secret documents. And it’s up to the public to interpret them. So I have no stakes in any elections. And you know, I’ve had my own row with the Trump administration over his, you know, encouragement of waterboarding and these types of things. So I’m no, you know, fan of the–of this administration. But I’m just saying that the information that WikiLeaks and Assange published about Hillary Clinton was true information, and it did not take away the liberty of the U.S. voter to make up his mind and to decide which candidate he preferred. So if that information leads to her not being elected, that’s just democracy. In my view. And so I’m not an expert on electoral processes, but it does not–it does not point to interference with U.S. elections.

RS: Well, and also, you are an expert, because we claim in the U.S.–it’s part of an America-centric view, but we claim that our Constitution is the gold standard for the world. We claim limited government, checks and balances, an American refinement on what the Greeks and the Romans and everyone else left us, or Confucius and other strains of political philosophy. And these are supposed to be universal ideas. We’re proclaiming them in Hong Kong right now, and elsewhere. And so what we’re really talking about–and it gets to the fourth point of your column, and I want to get people to read this column, “Demasking the Torture of Julian Assange”–you can get it on Medium. I guess Medium is a self-publishing place; we’re going to get to why you’re there and not in the New York Times. But I want to get to this last point, which is the shoot-the-messenger point. And you’re really quite compelling in this regard. You’re not somebody who thought you would like Julian Assange. You bought the propaganda against him; you know, this egomaniac, holed up in this, unnecessarily in this embassy, and with his cat, and doing all sorts–because there’s all these rumor-mongering. And what you really have is a full-blown campaign to shoot the messenger. To, you know, distort the debate. And you end up talking about that in a very compelling way. You’ve actually met him, and you’ve examined the circumstance of his time at–and you have defined this as psychological torture that he’s been put through.

NM: Ah, yes. And you know, I knew when I was going to visit him, because I was so reluctant and careful initially, I had to have a very strong, objective evidence basis for whatever result that was going to publish afterward. So I took with me two very experienced medical experts, a psychiatrist and a forensic expert. Both of them have worked decades to examine torture victims in various, in various circumstances. So I took both of them with me, so I didn’t just have one, but I wanted to have two independent medical opinions of very experienced experts. And we had four hours with Assange, and we spent three of those four hours on pure medical examinations, psychiatric examinations. And we applied recognized, universal standards and protocols, medical protocols for the examination of torture victims, to document and identify symptoms of torture, and to distinguish symptoms of torture from other medical, you know, symptoms that you would find with any prisoner. Any prisoner is stressed or depressed because he’s in prison, right? So that’s not torture. So these people know what they’re doing. And both of them came to the conclusion that he shows all the signs of, that are typical for a person who has been exposed to psychological torture on a prolonged period of time. That was the conclusion, the medical, evidence-based, forensic results of this examination. As the Special Rapporteur on torture, I’m an international lawyer, so I’m now looking at–well, he shows all these symptoms; that does not necessarily mean anyone wanted to torture him, yet; he just shows the medical symptoms. But then I had to look at, well, what could have caused these symptoms? Because you don’t get these symptoms overnight; it takes years to develop these types of symptoms. For the last almost seven years, he has been locked up in the same room of the embassy. So we have a very controlled environment where we can count on the fingers of our hands the major factors that could have influenced his life and could have caused these symptoms. So–so with a relatively high degree of certainty, we were able to identify the causes and effects. And so what I saw is that he has been exposed to a concerted and kind of sustained campaign of mobbing, first of all. Mobbing is something very serious; it’s where you shame and insult someone, you intimidate people. But it’s always the collective turning against an isolated individual. We know it from school; we know it from the workplace, from the Army, where the whole unit might turn against one member. It can cause people to commit suicide, even in this isolated environment. Now, in Assange’s case, basically the whole world ganged up against him. So wherever he turned, except the Ecuadorian embassy, he was under threat. And he–he knew he was not going to get a fair trial if extradited to the U.S. He knew he was not going to get a fair trial if extradited to Sweden, the way they prosecuted their trial. He knew he was not going to get a fair trial in the U.K. either. And what has been done to him since the arrest proves that point. And also, in the end, with the new president in Ecuador since 2017, the Ecuadorian government also turned against him and started harassing him inside the embassy. So he has been surveilled 24 hours a day, 24 hours seven, in his private rooms, ah, the video cameras, he had no privacy whatsoever for several years. He was–he was threatened, so several officials in the U.S. called for his assassination; even prominent personalities in the U.K. did the same thing. He was ridiculed in countless media outlets, making fun of him; he was obviously vilified as a sleazy rapist. So this all sounds a bit not so serious, but if you’re exposed to this as an individual, over several years–and you don’t have a family around you, you don’t have a sane, protective environment around you–it will cause very serious psychological consequences. And it actually destroys your personality. So it’s–it’s actually quite easy to link the causes and effects in this case. And that obviously links up with the judicial persecution that we’ve just described before, and then also it’s exacerbated by the fact that he is locked up in the embassy; he doesn’t have access to a doctor when he had a tooth inflammation; he had to take very, very strong painkillers for several years. So all of these factors add up, add up, add up. And at some point, a person will break and develop serious psychological symptoms.

RS: Well–I just want to push this a little further. Because you have devoted much of your adult life to examining this torture, violation of human rights, and so forth. And we indulge a convenient cop-out, which is we’re always the lesser evil. Or we do it by mistake, or it’s an aberration, or don’t draw big conclusions from it. And so, you know, if another country in the world engages in this practice, then it’s easy to condemn them. But the fact is that the U.S. has, in the matter of torture, set a pattern for the world. I mean, we have said when we feel we face this threat that we did after 9/11–which was not the biggest threat any country in the world ever faced. They’ve had enemies, every country has had enemies, and existential threats and so forth. But we said, after this 9/11 attack, you know, all restraints are off. All restraints are off. And we say it in pursuit of war, you know; the idea that the first casualty of wars is truth. You know, well, we have enemies; we get to lie about it. And that becomes a very dangerous narcotic, in a way. You know, England, for example; Sweden, United States. Yes, they make mistakes. But what you’re really describing here is a systematic pattern of suppressing truth, maybe more effectively than even in an overtly totalitarian country. That seems to me what’s happened. We are able to make a non-person–we, I take collective responsibility–the U.S. has been able to make a non-person out of Chelsea Manning and out of Julian Assange. They tried to do it with Ellsberg, and it was only a fluke in that trial because Richard Nixon, the president, had tried to bribe the judge with an appointment, that there was a mistrial; there was never really a resolution. But you know, we have here a test of whether you mean it by these checks and balances, or are they just a fig leaf?

NM: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. And I think it’s very important that, you know, you don’t need to like Julian Assange. You may even think that perhaps–and you know, I don’t know. Maybe he did commit some kind of a sexual assault at some point. Maybe he did, you know, do this that and the other, break the rules here and there. I don’t know, I’m not saying he is an angel. But I’m saying that what is being done with him stands in no proportion to whatever he could have committed. And that the motivation here is not to do justice; the motivation is to make an example of him so you can discourage others from following his example, from imitating what he has been doing. Because obviously, when you have platforms like WikiLeaks and systems where whistleblowers can submit secret information anonymously, it becomes extremely difficult for governments to control the information that goes out. And especially, obviously, information about wrongdoings, corruption, crimes, and so on. They can handle one WikiLeaks and one Assange, perhaps, but they won’t be able to cope with 10,000 of them, you know, popping up throughout the world. So I think that’s why not only the U.S.–this is not just a U.S. worry. Why is the U.K. cooperating so closely with them? Why is Sweden cooperating so closely with them? Why is now Ecuador, you know, cooperating so closely with, and flunking all principles of due process of law, just to make sure that an example can be made out of Assange? Because governments the world over, they dislike these types of uncontrolled elements that will, you know, come up with secret information and publish it. And so my assessment really is that our democratic oversight seems not to function anymore. That’s why we have organizations like WikiLeaks popping up and taking their place. If our media would function, if they would actually keep our governments under control, if the judiciary would keep our governments in control–and actually prosecute torture–if they did their job, we would need no WikiLeaks. But obviously, now we have these kind of rogue organizations coming up and filling that role, because the institutions we have created and appointed are not doing their jobs anymore.

RS: Well, I hate to say this to somebody who is as thoughtful and courageous as you, I think you are, I believe you are. And I know you’re an expert on these questions. I think you’re being too charitable to the past. And we all tend to do that. I–you mentioned, you know, the New York Times and the Washington Post and the Pentagon Papers. But they had printed lies about the Vietnam War; they had basically gone along with the official government account. Media, establishment media, generally in these Western societies, have gone along with the dominant narrative. And there was some room, some room to question, and sometimes they did. But you know, as they say, the My Lai massacre was revealed by Sy Hersh in an alternative publication, I think it was called Dispatch News, and then it got picked up. The Pentagon Papers required a whistleblower like Daniel Ellsberg to tell us what we really should have been told all along about why we were in Vietnam, and the fallacy of it. And maybe one positive thing to come out of this whole incident–and maybe this is a good point to conclude–maybe, yes, the internet has a lot of problems. The establishment looks at it and says, oh, it’s out of control, fake news, blah blah blah. But Julian Assange, as you have pointed out, revealed not fake news–he exposed fake news. He exposed the fake news that we don’t torture. He exposed the fake news that we don’t kill civilians. He exposed the fake news that–I mean, all of those cables about what we said to the Saudis and what we said to other embassies–that was real news. And it was real news that was very easy to conceal. Now, in the day of the internet, the real threat of–and I’m going to say, it’s not an accident or just, you know, why are they going after–they’re going after Julian Assange, and they will go after Edward Snowden if they can get their hands on him. And if the Chinese government had grabbed him they would have been very happy, and if the Russians had turned him over they would be very happy, so they wouldn’t complain about totalitarian governments. And the real threat of an Edward Snowden, of a Chelsea Manning, of a Julian Assange is that in the day of the internet, as long as it remains relatively open, you can’t keep these terrible secrets that if the public knew–public anywhere knew–they’d throw these guys out of power. Isn’t that really what’s at stake here?

NM: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. And I think, you know, to also take this on a very generic point here, I think this is really not just about good people and bad people. We have to just realize it’s about human nature. We know from neurological research that, you know, power intoxicates. Whoever you give unchecked power to, will abuse it at some point. It’s–you know, if you want to know what human nature is like, go on a highway, remove all the speed controls, tell people you’re not going to be checked for speed limits–who is going to respect a speed limit? You know, it’s not because they’re bad people; it’s just because people, when they know they’re not being controlled, well, they tend to use that, you know, to take advantage of that. And obviously, when you give to someone huge amounts of power and money, and you don’t subject them to control by the judiciary or the media or the public, they will end up abusing it. So it’s very important. It’s not just a moral issue, it’s very important as a global governance and national governance issue, that we ensure that there is scrutiny, the checks and balances work, and that there is transparency. The right to know the truth is absolutely crucial if we want to have a balanced and democratic society.

RS: Yes. And the other point that–let me throw in as a little editorial–ah, the internet is the worst and the best of all worlds. And if governments can control it and punish the dissenters on the internet, and hound them out of existence, ah, then the internet because an incredible, effective source of surveillance and intimidation. And if you have free spirits and a relatively open internet–and certainly Julian Assange has been an incredible free spirit, and even in the annoying senses of those words–and you can eliminate those voices, you have eliminated the prospect of this internet world being a new source of freedom, and instead it becomes a new source of intimidation, a very effective one. So I want to thank Nils Melzer. And you know, I haven’t done you credit with the introduction and everything. But he’s the Human Rights Chair of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. He’s a Professor of International Law at the University of Glasgow. He has since November 2016, he has been the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. And he has really delved into this Julian Assange case. And I compared it to J’Accuse…! from Emile Zola and the Dreyfus case. I think your work has really been the most significant on this case, and I am appalled that the media that benefited, made money off Julian Assange’s leaks, and Edward Snowden’s leaks, is so eager to turn its back on their news source, and a fellow publisher; that’s what Julian Assange is. But that’s all the time we have.

The article, “Demasking the Torture of Julian Assange,” we’ll have it here on our KCRW website and on other places; you can get it through Medium and read it yourself. Our engineers for KCRW are Kat Yore and Mario Diaz. Joshua Scheer produced the show. A special thanks to our producer here at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, Sebastian Grubaugh. And see you next week with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.