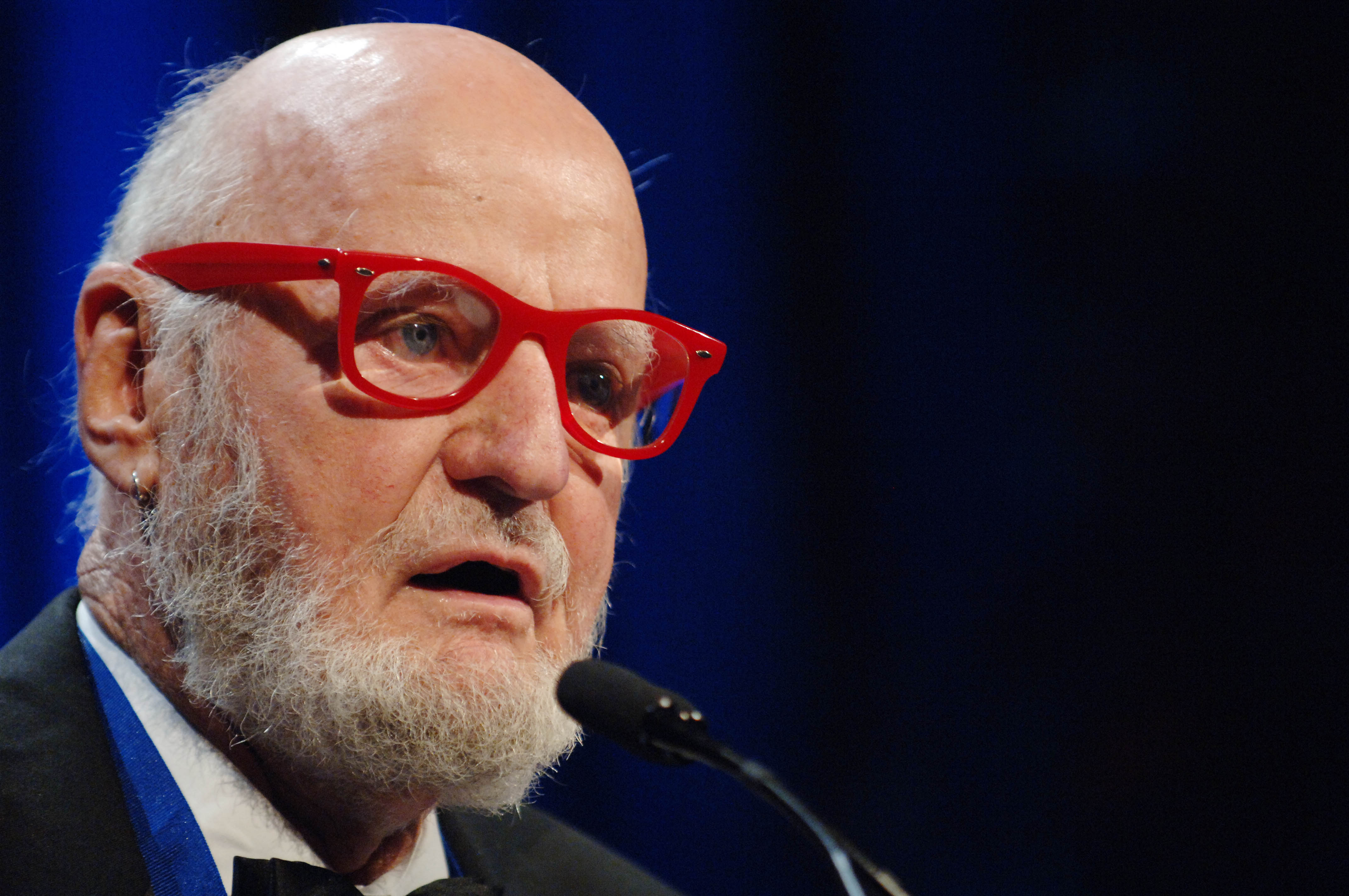

Lawrence Ferlinghetti Is Still Revolutionary at Age 100

The legendary poet, who is now 100 years old, can be described by nearly enough epithets for every year he's been alive. Henny Ray Abrams / AP

Henny Ray Abrams / AP

Legendary poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who turns 100 years old on Sunday, can be described by nearly enough epithets for every year he’s been alive. Just take a look at three-time poet laureate Robert Pinsky’s recent description of the centenarian in The New York Times:

Poet, retail entrepreneur, social critic, publisher, combat veteran, pacifist, poor boy, privileged boy, outspoken socialist and successful capitalist, with roots in the East Coast and the West Coast (as well as Paris), Ferlinghetti has not just survived for a century: He epitomizes the American culture of that century.

Specifically, he has been a unique protagonist in a national drama: the American struggle to imagine a democratic culture. How does the ideal of social mobility affect notions of high and low, Europe and the New World, tradition and progress? That struggle of imagination underlies the art of Walt Whitman and Duke Ellington, Emily Dickinson and Buster Keaton. It also underlies a range of American issues, from the segregation of public schools to the reality of human-caused climate change. Those political issues involve our interbreeding of the highbrow and the vulgarian in a supercharged process whose complexities defy simplifying terms like “culture wars.”

The founder of the San Francisco landmark City Lights bookshop rang in the turn of his very own century as his adopted city—he’s originally from New York—celebrated “Lawrence Ferlinghetti Day,” one of many centennial celebrations held throughout March in his honor.

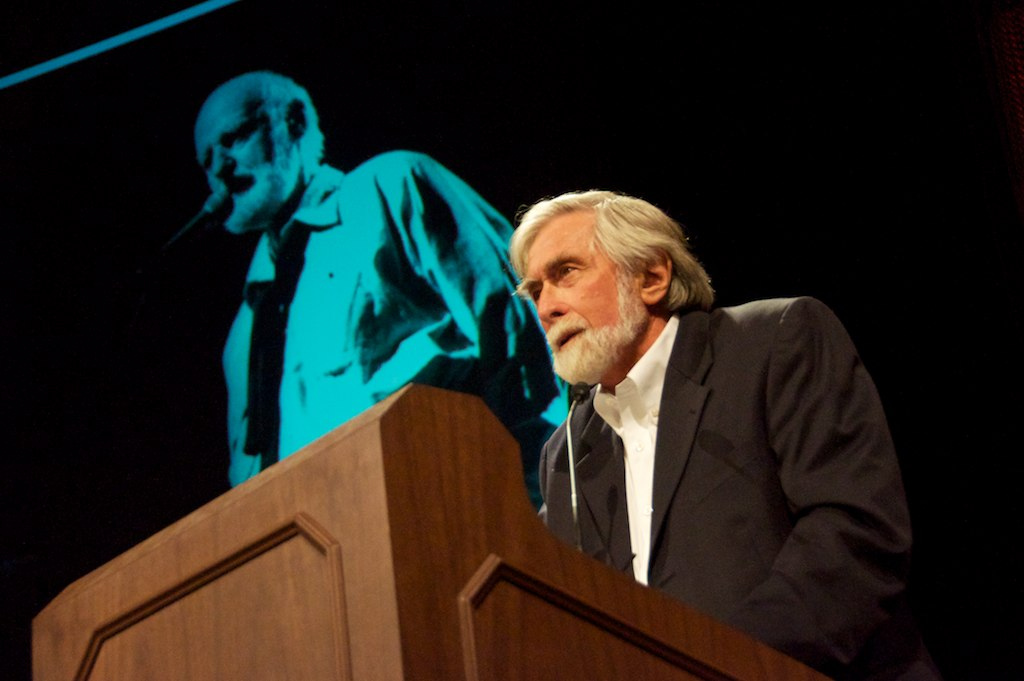

Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer, who once worked at City Lights and has been a lifelong friend of Ferlinghetti, writes about the city’s festivities, “Lawrence turns 100 today and poetry owns the Barbary Coast in a wild romp of readings at bars, galleries, and other watering holes in North Beach around Broadway and Columbus where City Lights Bookstore still stands as the best rebuke to the slick mindlessness of capitalist culture that now overwhelms Ferlinghetti’s once beloved bohemian San Francisco.”

While the journalist and the poet have recorded several of their conversations, their most recent discussion, produced by filmmaker Stephen French, can be found in the media player below. In it, Scheer and Ferlinghetti talk about the beginning of City Lights and its roots in an egalitarian desire to both promote and protect writers, as well as provide a safe space for local artists to congregate.

“What Lawrence represents is the ultimate uncompromising spirit,” says Scheer, “not in the sense of some pompous asshole who says, ‘I know the truth and here it is,’ but in the sense of saying, ‘I am a bullshit detector … whose main concern is that the average person and artists and poets and everybody not get fucked over.” Below is a video about City Lights, the San Francisco mainstay that was a literary home to Beats such as Allen Ginsberg—City Lights published his famous poem “Howl” in 1956, a publication that the founder says “put City Lights on the map”—and has continued to play an important role in protecting free speech, especially dissent, since its founding in 1953.

In addition to the Beats, writers such as former U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera and Karen Finley, among many others, found both support and inspiration at City Lights throughout its several-decades-long run.

Scheer, who describes himself as a “wannabe Beat poet,” also tells Ferlinghetti in the earlier conversation, “You were part of a post-WWII generation [that] knew even the good war was a horror.” This is in large part why the journalist says he “found a home at City Lights,” where he began reading about Vietnam and, with Ferlinghetti’s support, traveled to Southeast Asia to do some of the earliest critical reporting on the war.

On top of the many hats Ferlinghetti has worn throughout his life, he always wears that of a World War II veteran, as Scheer notes. His experiences during the war led the poet to become an “instant pacifist,” in his words. Here’s an excerpt of Ferlinghetti’s retelling of his time in Nagasaki after the atomic bombing from a Scheer Intelligence episode.

When we went over to Nagasaki, it was total devastation. It was like a landscape in hell. What was left of bodies had all been cleared away by the time we got there, which was about seven weeks after the bomb had been dropped…. It was acres of mud, with bones and hair sticking up out of it. And as I’ve said before, it really made me an instant pacifist. Up to that time, I’d been a good American boy, in the boy scouts, etc…Nagasaki really woke me up.

But Ferlinghetti isn’t only concerned with the politics of his past, but also of the present. A recent poem he’s written about the United States’ 45th president, “Trump’s Trojan Horse,” is a condemnation of a White House from which Trump’s “men burst out to destroy democracy and install corporations as absolute rulers of the world.”

On Ferlinghetti’s 100th birthday, his new novel “Little Boy” is being published by Sterling Lord.

Little Boy’s story begins, abruptly, with Ferlinghetti’s mother abandoning her newborn son after his father dies of a heart attack. A beloved, childless aunt whisks baby Lawrence off to France. The story rushes forwards, with dizzying circumlocutions, from there. The patchwork of biographical narrative and freewheeling forays into societal commentary (“the icebergs melting and all that and humankind the temporary tenant floating toward the precipice unable to stop itself and its self-destruction”) makes the book feel like a memoir.

That’s not a word Ferlinghetti uses to describe his new book. “I object to using that description,” he says. “Because a memoir denotes a very genteel type of writing.”

Little Boy is in many respects a challenging read about a hardscrabble experience. But it’s not without its genteel moments – as when Ferlinghetti describes his early years living with his aunt, who at one point was hired as the governess of a wealthy east coast family. The Bisland residence was an enormous mansion in Bronxville, New York, just north of Manhattan. Ferlinghetti describes how the classically educated family patriarch, Presley Bisland, would fire questions at him – “Young man, you’ve been to school – who was Telemachus?” – and ask him to recite poetry for him at the dinner table in exchange for cash.

What’s been clear for several decades now to anyone paying attention to history-in-the-making, is that the poet, publisher, activist, veteran, rebel—again, the list is endless—has left an indelible mark on America’s political and literary landscapes that will likely last hundreds of years, if not more.

Read more about Ferlinghetti in the following short biography from City Lights’ website:

Your support matters…A prominent voice of the wide-open poetry movement that began in the 1950s, Lawrence Ferlinghetti writes poetry, translation, fiction, theater, art criticism, film narration, and essays. Often concerned with politics and social issues, Ferlinghetti’s poetry counters an elitist conception of art and the artist’s role in the world. Although his poetry is often concerned with everyday life and civic themes, it is never simply personal or polemical, and it stands on his grounding in tradition and universal reach.

Ferlinghetti was born in Bronxville, New York on March 24, 1919, son of Carlo Ferlinghetti, an immigrant from Brescia, Italy, and Clemence Mendes-Monsanto. Following his undergraduate years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he took a degree in journalism, he served in the U.S. Navy in World War II. He was a commander of three different submarine chasers in the Atlantic and saw action at the Normandy invasion. Later in the war, he was assigned to the attack transport USS Selinurin the Pacific. In 1945, just after the atomic bomb obliterated Nagasaki, he witnessed firsthand the horrific ruins of the city. This experience was the origin of his lifelong antiwar stance.

Ferlinghetti received a Master’s degree in English Literature from Columbia University in 1947 and a Doctorate de l’Université de Paris (Sorbonne) in 1950. From 1951 to 1953, after he settled in San Francisco, he taught French in an adult education program, painted, and wrote art criticism. In 1953, with Peter D. Martin, he founded City Lights Bookstore, the first all-paperback bookshop in the country. For over sixty years the bookstore has served as a “literary meeting place” for writers, readers, artists, and intellectuals to explore books and ideas.

In 1955, Ferlinghetti launched City Lights Publishers with the Pocket Poets Series, extending his concept of a cultural meeting place to a larger arena. His aim was to present fresh and accessible poetry from around the world in order to create “an international, dissident ferment.” The series began in 1955 with his own Pictures of the Gone World; translations by Kenneth Rexroth and poetry by Kenneth Patchen, Marie Ponsot, Allen Ginsberg, and Denise Levertov were soon added to the list.

Copies of Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems were seized by authorities in 1956 and Ferlinghetti was arrested and charged with selling obscene material. He defended Howl in court, a case that drew national attention to the San Francisco Renaissance and Beat Generation writers, many of whom he later published. (With a fine defense by the ACLU and the support of prestigious literary and academic figures, he was acquitted.) This landmark First Amendment case established a legal precedent for the publication of controversial work with redeeming social importance.

In the 1960s, Ferlinghetti plunged into a life of frequent travel––giving poetry readings, taking part in festivals, happenings, and literary/political conferences in Chile, Cuba, Germany, the USSR, Holland, Fiji, Australia, Nicaragua, Spain, Greece, and the Czech Republic––as well as in Mexico, Italy, and France, where he spent substantial periods of time. A resolute progressive, he spoke out on such crucial political issues as the Cuban revolution, the nuclear arms race, farm-worker organizing, the Vietnam War, the Sandanista and Zapatista struggles, and the wars in the Middle East.

Ferlinghetti’s paintings have been shown at a number of exhibitions and galleries in the U.S. and abroad. In the 1990s he was associated with the international Fluxus movement through the Archivio Francesco Conz in Verona. His work has been exhibited both nationally and internationally, including a 2010 retrospective at the Museo di Roma in Trastevere, Italy, and a group exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2016. His works are in the collections of the Smithsonian Museum of American Arts and the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, and most recently exhibited at a one-man show at San Francisco’s Rena Bransten Gallery in July 2016.

He was named San Francisco’s Poet Laureate in August 1998. He has been the recipient of numerous awards: the Los Angeles Times’ Robert Kirsch Award, the BABRA Award for Lifetime Achievement, the National Book Critics Circle Ivan Sandrof Award for Contribution to American Arts and Letters, the American Civil Liberties Union’s Earl Warren Civil Liberties Award, the Robert Frost Memorial Medal, and the Authors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2003, he was was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and in 2005 the National Book Foundation gave him the inaugural Literarian Award for outstanding service to the American literary community. In 2007 he was named Commandeur, Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. In Italy, his poetry has been awarded the Premio Taormino, the Premio Camaiore, the Premio Flaiano, and the Premio Cavour.

Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind (1958) continues to be one of the most popular poetry books in the U.S., with over 1,000,000 copies in print. A prolific author, Ferlinghetti has over a dozen books currently in print, and his work has been translated into many languages. Among his poetry books are These Are My Rivers: New & Selected Poems, 1955-1993(1993), A Far Rockaway of the Heart (1997), How to Paint Sunlight (2001), Americus Book I(2004), Poetry as Insurgent Art (2007), Time of Useful Consciousness (2012), and Blasts Cries Laughter (2014), all published by New Directions. His two novels are Her (1960) and Love in the Days of Rage (2001). City Lights issued an anthology of San Francisco poems in 2001. He is the translator of Paroles by Jacques Prévert (from French) and Roman Poems by Pier Paolo Passolini (from Italian.) In 2015 Liveright Publishing, a division of W.W. Norton, published his Writing Across the Landscape: Travel Journals (1960-2010). In 2017, New Directions published an anthology of his work titled Ferlinghetti’s Greatest Poems, and his latest book is a novel, titled Little Boy (Doubleday, 2019).

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.