Humans Are Robbing Other Species of Space

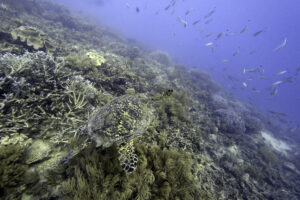

As human growth adds to our numbers and demands, other species’ survival chances shrink. Zoi Koraki / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Zoi Koraki / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

There is only one Earth, but human growth is ensuring that it carries steadily more passengers. And that leaves less and less room for humanity’s companions on board the planet.

The Nile lechwe is an antelope that lives in the swamps of Ethiopia and South Sudan. Its Linnaean name is Kobus megaceros and it stands a metre high at the shoulders so you couldn’t miss it. Except that you could.

That is because it is one of at least 1,700 species identified by biologists to be at risk from human action: quite simply, as humans take an ever-greater share of animal living space, the animals’ chances of survival dwindle rapidly.

So the Nile lechwe joins the Lombok cross frog of Indonesia (Oreophryne monticola) and the curve-billed reedhaunter (Limnornis curvirostris) that lives in the marshes of north-east Argentina to be at risk of extinction by 2070, simply because humankind will intrude on at least half of their geographic ranges.

“It is often the far-away demand that drives these losses – think tropical hardwoods, palm oil or soybeans …”

Biologists, conservationists and climate scientists have been warning for decades that the dangerous combination of human population growth and climate change driven by human-induced global warming puts whole ecosystems at risk, and will hasten the extinction of many species that are already shrinking in numbers.

These include many that underwrite the provision of food, medicine, fabric for the world’s cities and air and water purification systems on which human civilisation is founded.

Most such warnings have been based on projections of economic growth, urban demand and climate change. US researchers approached the challenge in a different way.

They report in Nature Climate Change that they collected data on the geographic distributions of 19,400 species and combined this with four different projections of future changes in land use – a euphemism for scorched or felled forest, drained swamp, ploughed grassland and so on − in the next 50 years.

Shared responsibility

And they identified 1,700 species that, even with moderate changes in land use, will lose roughly a third to a half of their present habitat by 2070. This total includes 886 species of amphibian, 436 kinds of bird and 376 mammals. And this loss of living space accentuates the hazard to their lives and futures.

Many animal citizens of Central and East Africa, Mesoamerica, South America and Southeast Asia are particularly at risk. And, the authors warn, even though such losses would happen in national territories and involve species with limited range, the responsibility for their loss would be global.

“Losses in species populations can irreversibly hamper the functioning of ecosystems and human quality of life,” said Walter Jetz, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist at Yale University in Connecticut, one of the authors.

“While biodiversity erosion in far-away parts of the planet may not seem to affect us directly, its consequences for human livelihood can reverberate globally. It is also often the far-away demand that drives these losses – think tropical hardwoods, palm oil or soybeans – thus making us all co-responsible.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.