The Uncomfortable Truth About Journalism’s Glory Days

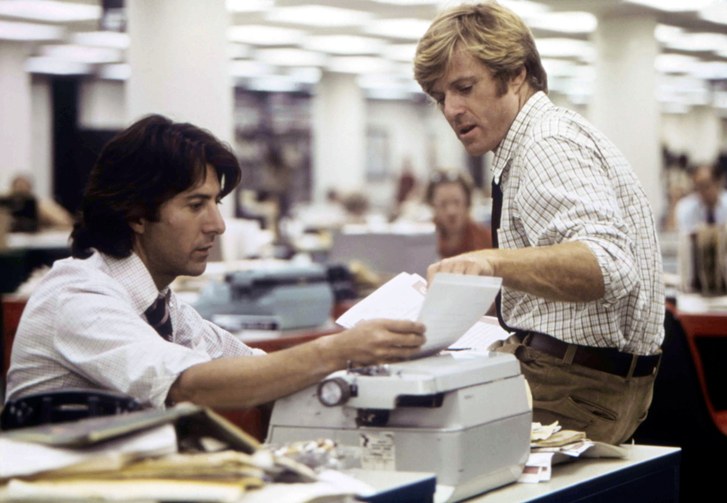

Los Angeles Times reporter and "Don't Stop the Presses" author Patt Morrison examines the past, present and future of the fourth estate. Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford star as Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward in "All the President's Men" (1976). (Warner Bros.)

Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford star as Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward in "All the President's Men" (1976). (Warner Bros.)

Listen to Scheer and Morrison as the two veterans grapple with the past and discuss the vital public service of journalism that is integral to American democracy. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player.

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where I hasten to say the title–given to me by our station [Laughs]–reflects the intelligence of the guests, rather than the host. And in this case, it’s Patt Morrison, a legendary journalist. And I use that in a really complimentary sense; a pioneer, came to the L.A. Times when she was 19 from Occidental College. A college, by the way, that Barack Obama rejected after two years, a sore point over here in downtown L.A.–

Patt Morrison: He didn’t like the weather.

RS: [Laughs] He didn’t like the weather, he liked the Ivy League, and he wanted to be in the fast lane. I do want to say, this book called Don’t Stop the Presses: Truth, Justice, and the American Newspaper. And it has a foreword by Dean Baquet, the executive editor of the New York Times. Has great quotes by Norman Lear, Ken Burns, Carl Reiner. And who wouldn’t love this book? You know, it’s a love letter to print. And at a time when print is on life support–we can discuss the degree to which it’s on life support–it’s really great to have what at first appears, it’s Angel City Press, and at first appears to be kind of a scrapbook, or certainly a coffee table book. However, when you read [Don’t] Stop the Presses, you manage, Patt Morrison, to raise really significant issues, not just about what we have lost with print and so forth, but some basic issues of journalism in general. And I want to get right to that. We have only a half hour, you’re a really smart veteran journalist, and I want to raise some tough issues here. And I have a precedent for doing that, because when you interviewed me for public radio on my last book, when I came in there, I was alarmed in the studio to see you had almost every page marked up and dog-eared, and–

PM: Because each was so good!

RS: No, because that’s–you were doing your job, and that’s what we want to do here. And I spent time with this book, and it’s a serious book. I want to stress that; it’s not a scrapbook. And I want to turn to page 59, because it seems to me there, you raised a fundamental issue that cuts through the nostalgia. OK, yes–nostalgia for print is warranted. They were great days, and there was great variety. And one of the things that’s terrific about Don’t Stop the Presses, we’re not just talking about the New York Times and the L.A. Times, Washington Post–we’re talking about podunk papers. So there’s no doubt the history of print, going back to the wall posters, going back to somebody you don’t mention in this book, by the way, Tom Paine and his pamphleteering. That whole tradition that really gave us the American experiment. You know, as you say, if somebody had a printing press, they schlepped it to a battle zone, they schlepped it anywhere and suddenly they were in business, whether that was the Civil War or earlier. And it’s a great tradition; it is one that deserves to be captured. This book, Don’t Stop the Presses, does a better job of it than anything I’ve seen lately. In fact, maybe that I’ve seen in a long time. And I want to take us to page 59, my favorite quote about journalism, which comes from a guy named A. J. Liebling who was the media critic for The New Yorker. And he said something that I just think really has to be there: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” And in your book, while you pay homage to all the great journalists–a lot of them, anyway–you recognize the contradictions. That the good old days were far from perfect. And that statement, let’s start with that: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Because the two of us worked for the Chandler family; we happened to work for a good Chandler, in the sense of a good publisher, Otis Chandler. But there were Chandlers who were not good publishers from the point of view of the community. They stole the water from Northern California, they wrecked the environment, and so forth. They rigged politics. And this was true of Hearst, as you point out in your book; it was true of Pulitzer, and all–Bancroft, all the great families. So this book, while a tribute to the print journalist, recognizes the enormous contradictions. And it brings it up to the current moment. Right now print is, you know, having a flowering because of all–oh, we’re not Trump, there’s Trumpwashing; if you’re not Trump, you’re virtuous, you know; the kind of, Dean Baquet says it in the foreword to your book. But the fact of the matter is, we’re now being saved by billionaires, and billionaires have conflict of interest when it comes to journalism.

PM: The paradox is that we were always in the hands of rich people, because those were the people who owned the printing presses. Some of them were only comparatively rich, some of them were truly rich, like the Jeff Bezoses of the world. And a lot of them took up newspapers, took on journalism as an adjunct, as you pointed out, to money-making enterprises like real estate, or to their own political careers. Warren Harding owned a newspaper, the Marion Star in Ohio, before and even while he was president of the United States. So the paradox is, here’s a public service–journalism, which is mentioned in the Constitution–that’s in the hands of private owners whose intentions and whose wishes we may not know, and we may certainly have no control over.

RS: Yeah, well, let’s take that a bit further. The saving grace of all that was some notion of a free market. You didn’t require that much capital. That’s why in your book you mentioned, even at the time of the revolution or before it, the reason you had ferment is it didn’t take a lot of money to publish a wall poster. You know, Tom Paine, after all, published because he was able to seduce the wife of the printer who had a press, or so legend has it. And you know, you had all sorts of rascals and wonderful people and brave people doing this. And then, even in the heyday that you describe of the L.A. Times, the New York Times, the Washington Post, they had competition. There were lots of papers, and when I was growing up in New York there were, I don’t know, 25 newspapers competing with the New York Times and the Herald Tribune. Now you’re in a situation of media concentration. And media concentration, by the way, abetted by some people who claim to believe in the free press–like Bill Clinton, who did the Telecommunications Act that allowed television owners to buy print in the same market and so forth. And now, it’s a situation where print is increasingly owned by a very tiny group of ultra-wealthy people who can afford, in the case of the Washington Post–ah, here’s $250 million, I’ll buy your paper, maybe I’ll have some fun with it–besides I’ll make it, in a few months, I’ll make it back. And then the question is, can you have a free press? You now, as I say, work at the L.A. Times; you have a pharmaceutical billionaire who, people are happy that he saved the paper from bankruptcy. But take us on this trajectory of your book, from the wall poster and the penny press and the town crier, to the age of the billionaire publisher.

PM: The original publishers in this country, before the revolution, had to print under imprimatur of the crown, of the British crown. And if you wrote something the crown didn’t like, then you were in trouble. Look at John Peter Zenger; what he printed about the royal governor was the truth, but truth in English law was not a defense in libel. And so we established that as an American standard, truth as a defense in libel. And then because of the revolution, during the revolution you had newspapers taking the side of the new America, of the revolutionaries, helping to spread the word and create interest and support for the idea of independence. And then after the revolution, you had butting heads with John Adams and publishers of papers–he threw Ben Franklin’s grandson in jail because of the Alien and Sedition Acts. So the freedom of the press also required you to put your butt on the line and to put something at risk, to put something at stake–in some cases, your freedom. Thomas Jefferson changed all that when he became president. But you saw people who became newspaper publishers, who owned newspapers in this growing country, not because they were paragons of journalism, they were interested in the spread of information. They used the newspaper to further their real estate interests, to further their political careers, and journalism was kind of a side life. Sure, go ahead and cover the city council. Yeah, why not write about the police department in the meantime. But that wasn’t the thrust and force of what they were doing in journalism, what they were owning newspapers for.

RS: Yeah. But the saving grace, again, is that to the degree that you had a free market, and you didn’t require an enormous capital investment, and you could anticipate making money–a lot of people could start newspapers, OK, or small publications, or be pamphleteers. Now, we’re in a world where media concentration has gotten to the point that most of your smaller papers are collapsing, they’re no longer print, and so forth. I think there’s a bright spot to this in the internet; we can disagree about that, maybe, and we’ll get to that. But the fact is, you know, if you think about the L.A. Times that you went to work for, there were a lot of–there were other papers in town. And you know, if the L.A. Times didn’t deliver a good product, a believable product–after all, I went to work there for 29 years in one way or another. The only reason they hired me is everyone thought this paper had been a tool of the Nixon administration and was ultra-conservative, they wanted–

PM: As it was.

RS: –yeah, and they wanted to “fix the Nix” a little bit, and they hired a few characters like myself, and they gave us quite a bit of freedom. But that was to suit a market that was relatively open and free. When you have your billionaire class coming in, they’re not subject to market pressure; they can lose lots of money; you know, so what. But they also can have a newspaper that probably isn’t inclined to talk about income concentration, power concentration, and so forth. And that’s the concern. At least with a free, relatively free open market, people could come along with a rival product. I want to suggest to you that, yes, the book is right to worry about what do we get in the place of print. And people should have it, they should have it on their coffee table, this book from Angel City Press–let’s get that out of the way. I think Don’t Stop the Presses by Patt Morrison, write it down, with a foreword by Dean Baquet–Truth, Justice, and the American Newspaper–I’d like people to buy this book. It’s a very important reminder of the vitality, openness, of the press. So let’s put that away, I’m endorsing–

PM: Thank you, Bob.

RS: That’s, right, OK, I’m endorsing the book. Now, however, I want to discuss some of the serious issues raised in this book. The most important is, were the good old days really better than the current? And as the editor of something called Truthdig.com, and I’ve done a lot on the internet, I dispute that notion. I think, yes, the internet has a lot of problems, a lot of–and if they do away with net neutrality, and they destroy it, we’ll be in trouble. But I think we’re getting a lot of really terrific journalism on the internet. We can’t pay people what they need to be paid; the profession is in trouble, the occupation is in trouble. But you can’t deny that whether it’s coming from individual citizens, or whether it’s coming from professors or so forth, there’s a lot of good information out there.

PM: I think you’re right, and I think the good old days weren’t nearly as good as we like to think. They were profitable old days, when there was a monopoly on advertising where you had department stores and you had local newspapers competing for that advertising, and writing the stories about what was going on in the small towns. And in the midsized towns, and in the cities like Los Angeles as well. But newspapers had tremendous blind spots about what they covered, partly because if you had a staff of middle class white men, those were the stories you saw reflected. And the idea of unheard voices and unseen faces that would have brought into the newspaper stories that reflected the community–you had papers that were devoted to things like this. Wasn’t in PM in New York–

RS: Yes.

PM: –that was a labor paper, that did a fantastic job. Afternoon papers like the Herald Examiner used to be more pro-labor and pro-working man, because that was the audience for those papers, before TV news came along. And so the blind spots in the newsroom are being filled in today by websites like Truthdig, by special interest websites. Like The Root, I think, does a wonderful job of covering African-American issues in a way that they have not been covered in mainstream newspapers in virtually all of American history. The pitfall of the internet is that when you think of Thomas Friedman saying the world is flat, I look at the internet and say the internet is flat. Meaning there’s no topography to really help you see what’s a reliable, reported, sound website like Truthdig–that really knows its sources, that copyedits its information–and some guy who uses the name of a newspaper to make it seem like “my publication, the Tribune, is the reliable truth,” and just spews out hate stuff or nonsense or conspiracy theories. So those are pitfalls that the newspaper itself, with some of the curating that it’s had historically–and like Truthdig does now–that helped to remedy that. It didn’t broaden its view, but it did a better job of what it actually put in, into the newspaper, of saying we’ve checked this out, we’ve looked into this, and this is what we find.

RS: Yeah. Well, one reason to check it out is you can be sued for defaming people, libeling people, and so forth. If you have a successful internet product, you’re also going to worry about being sued. So what we’re really talking about are the fly-by-night, hit, appear from nowhere, who owns them, transparency, and it’s certainly a valid concern. But I happen to teach at the University of Southern California, and I’m very inspired by our students and their relation to the internet in one important respect. If I can, or anybody can, get their interest in a subject–yes, they’ve been poorly prepared; they don’t know about the Korean War. High school, despite–we have very high SATs [Laughs], very well prepared students–they don’t know about the Korean War, they don’t know the United States leveled Korea during the Korean War, destroyed every single structure in what was then North Korea. They don’t know that, you know. But, if somebody raises that with them, they can say wait a minute, is this professor giving me fake news? You know what? When I leave class, or even while I’m in class, I can check out original documents. I can get alternative sources. I can do what a kid couldn’t do in the old days, maybe if they went to the 42nd Street library in New York. But now–

PM: Rather than the 42nd parallel, or 43rd parallel. [Laughs]

RS: OK, but now somebody can actually get original documents. They can say, hey, this professor’s full of it. Or, you know, Bill O’Reilly’s full of it, or what have you. George Soros is full–I mean–

PM: And in a way, publish, with their own websites.

RS: Yeah, but also, facts do matter. And this is where I think the internet gets a bad rap. My concern is not the noise on the internet; my concern is people who are now saying the internet is so flawed we need to regulate it. We need to attack net neutrality, we–you know, the traditional newspapers that are struggling–and by the way, I think the L.A. Times, the New York Times are doing a relatively good job under difficult circumstances. But the fact of the matter is, they’re using this internet-bashing as a way of justifying their own existence and legitimacy. And that’s just not fair. The fact of the matter is, there was a lot of distortion in the old days. First, we didn’t know–when I was growing up in New York City, and I’m an old guy now, I’m 82, no one ever wrote in the New York Times about it being segregated in baseball, or basketball, or the whole South. You know, which was, by the way, the head of the Democratic Party was based in the South. And even more recently, I remember writing for the L.A. Times; I went back to the Bronx when the Bronx was burning, was destroyed, and has never really recovered, the borough that I grew up in. And if you relied on the New York Times, you didn’t know it.

PM: To take an example in the book, I reproduce an LAPD badge, an official badge for the LAPD, that was given to police reporters, cops–reporters who covered cops routinely. And instead of saying sergeant or lieutenant, it said “reporter.” They carried badges! Up until the point, around the Watts Riots, when what the newspapers were writing diverged from the official party line, from the cops. And the cops would say, I don’t think we’re going to let you have those badges anymore. That’s the kind of churn and lesson-learning that newspapers took the hard way–and that the internet has an advantage of doing in a much faster fashion, and hearing from a multitude of voices. That crowd that is allowed to take part now, thanks to the internet, can make reporting more honest, more diverse, and more reflective of what’s actually going on.

RS: Yes. And the terrific thing about Don’t Stop the Presses, Patt Morrison, is it’s a tribute to the reporters. [Laughs] OK, they’re the people who held these newspapers accountable; some of them quit their jobs. For instance, let’s take categories of people, women, to begin with. When you went to work for the L.A. Times, and I don’t want to [pigeonhole] you, but can you give me the year?

PM: Well, this was when I was 19 years old. Narda Zacchino was already at the newspaper–

RS: My wife-to-be.

PM: Your wife-to-be. A woman named Dorothy Townsend had argued her way over from the so-called soft side, the features section of the newspaper, to work in the hard news section. Because as someone pointed out, they had no trouble women going out at midnight covering society stories, but couldn’t possibly go out at midnight to cover murders. And so there were very few role models, very few women, certainly not people of color, who brought a reflection of the city, a diversity of ideas, a diversity of judgment, to the reporting. And that’s one of the reasons that newspapers were so static in a way, and why they didn’t do what publisher Otis Chandler said he wanted, “mass and class”–wasn’t reaching the masses, it was hieratic. Only now are we seeing a more demotic turn; as newspapers are disappearing, what’s rushing in to fill the void is those voices we didn’t hear from before.

RS: Yeah, and the big challenge did come from–well, for instance, the National Press Club had women in the balcony, I forget the person who wrote the book–

PM: Nan Robertson.

RS: Nan Robertson, Girls in the Balcony. Here at the Jonathan Club and the California Club, they didn’t let women in. So I think it was Celeste Durant was a reporter, black woman reporter at the L.A. Times, was the first one when someone was announcing for governor, I think it was Evelle Younger, said the L.A. Times will not cover this if I have to go in the back door. And so you’ve been a witness to this, and people need to know this history. Because it’s now sort of dismissed, yeah, affirmative action; yeah, you know, identity politics–no. The fact of the matter is, when you went to work at the L.A. Times, women were systematically discriminated against. And people of color very much so. So you know, your book reminds us of that. But let listeners in on this.

PM: Well, the idea that women could actually do the job of reporting was a new one in the seventies and eighties. We saw lawsuits against organizations like the New York Times because women were not being given the opportunities that they should have in the newsroom. And the readers suffered for this; the readers weren’t getting as much as they should. The same thing happened with people of color. You had terrific black-owned newspapers. I mean, there was a newspaper called The Planet that opened in Richmond, Virginia–the seat of the Confederacy–within a few years of the end of the Civil War, entirely staffed by African Americans. The Chicago Defender had tremendous influence among African Americans across the country, wrote about the Double V movement in World War II, victory against fascism, victory against racism. And yet these newspapers and people who worked for them were investigated because they were considered disloyal; they weren’t fully American, in the war effort or afterwards during the civil rights effort.

RS: Yeah, I want to bring up–well, let’s talk about race a bit here. And as a real blind spot, when the L.A. Lakers, when the Lakers came to L.A. from Minneapolis, as was typically the case you still had segregation in basketball–everybody knows about baseball–and you could only have two black players on the team, was the code and so forth. The L.A. Times didn’t write about it. Much later, they started writing about it.

PM: It was considered a matter of course, because there was nobody on the staff to say, wait–this is wrong, let’s analyze this.

RS: Right. And you know, your career, which we haven’t really gone into, but what you exemplify is boldness. [Laughs] You weren’t going to take it from anyone. And whether you did it on radio with your terrific interviews, or your terrific reporting, you stand out as also having a sensibility that we might find more in a woman than in a man. I mean, the whole argument always–Jack Nelson, who was the bureau chief of the L.A. Times in Washington said well, we would like to hire more women and minorities, but we’re going for the best person for the job. And I remember when, a legendary thing, somebody said well maybe the best person is not somebody in your social set, you know. Or maybe they have to be encouraged to come along. And there was a whole range of stories, including segregation in sports, that white sports writers, white male sports writers, would ignore. And then I think the most famous incident was the Watts Riots, when they couldn’t find a single black reporter at the L.A. Times–they didn’t even know where Watts was, this big riot happening in L.A.

PM: In fact there was a former Times reporter named Paul Weeks who covered civil rights issues, a white guy who had warned that this sort of thing was boiling. But you’re right, they ended up getting some guy from the advertising department and deputizing him as a reporter and sending him out, you know, where he would get picked up by the cops and write about what he overheard the cops saying about black people during the riots. But afterwards, he was given no support, no training, and of course he failed out, he flunked out. Because he didn’t fit the bill and the education and the checkmark kind of resume that white reporters had. And you saw this happen over and over again, tragically, in many newspapers. Black newspapers did a wonderful job of covering the black community, but that wall was virtually impermeable for decades.

RS: Yeah, America was an invisible segregated society, as opposed to South Africa were very much in the news after the war. Our army in World War II was segregated; every key aspect of our life was segregated. And this newspaper history of print ignored it, whether it was in the north or the south, with some brave exceptions that you write about in your book.

PM: Well, there was a woman named Ethel Payne, who was the queen of black journalism. She worked for the Chicago Defender; she covered black Americans in Vietnam. She was also on the White House coverage, she was a White House, official White House reporter. And her questions to President Eisenhower were so pointed and uncomfortable when it came to race, that supposedly the White House staff tried to find ways to get her credentials decertified, to get her credentials yanked, because she made him so uncomfortable. And remember President Kennedy at a press conference was asked by a woman reporter about equal pay, and he kind of made a joke out of the whole thing. This is how people of color and women were often treated, even when they were in the big game, in the mainstream game.

RS: Oh, when Helen Thomas was a leading White House correspondent, Gerald Ford, you know–I mean, she broke into the Gridiron Club, got a membership, which was key to networking and everything. And he made a joke of it at the press–in the middle of a serious question she was asking, I believe about the economy. So anyway, I want to say Don’t Stop the Presses does not whitewash the history. But what it does capture is the vitality, the energy; these were ink-stained wretches, these were people basically who went into journalism not for the money. You know, certainly didn’t go into print, and then once TV came in, that’s where the big money was. They did it out of love, obligation, perversity, or what have you. [omission for station break] We’re back with Patt Morrison. The book is Don’t Stop the Presses, Angel City Press, Truth, Justice, and the American Newspaper. OK, this is a good point on which to wrap it up, because people should understand the big takeaway here is not finding culprits, maybe these billionaires will be good and maybe they’ll be bad, or so forth, and we can cross–there’ve always been contradictions. After all, Franklin Roosevelt came from a wealthy family, and he was really for my money still, with all the contradictions, a very good president for working people. You know, and the country’s always been built on contradictions. But the thing that held the line for newspaper integrity, which comes across loud and clear in Don’t Stop the Presses, was competition. Competition–the capital investment was never that big in the old days that some upstart couldn’t do it, OK. You celebrate George Seldes, for instance, a legendary–you don’t celebrate, by the way, a few people I miss here–I.F. Stone and Murray Kempton, but you know, you’re not an East Coast person originally. But you do celebrate George Seldes, and he was a really terrific journalist who ended up being axed by different places because he dared challenge, you know, conventional reporting on foreign affairs and so forth. He then started a little publication called In Fact, which my garment-worker parents used to actually subscribe to in the Bronx.

PM: And newspaper reporters who couldn’t get their own newspapers to print their stories sent them to Seldes. So he would publish them.

RS: Right. And there were other models; I.F. Stone did the same thing, and so forth. So the free market was free enough that with very small capitalization–I think I.F. Stone did it in his home with his wife being the publisher, and he was the editor–when he got pushed out of the New York Post, I guess it was, or the Compass. Ah–you could do it, OK. And the market had its own regulation. The reason you had 20, or 25 newspapers in New York is they could find a market, OK. The problem right now is the market, as you point out in Don’t Stop the Presses, the model, the business model is broken. I would argue it’s not going to come back, it’s not going to come back–why? Because newspapers had a lock on advertising, on a certain kind of advertising, and that got broken, OK. And now the targeted advertising on the internet can pick up the readers of the L.A. Times without actually placing an ad in the L.A. Times–or in Truthdig, for that matter. So you don’t have that model, and that’s really a downer, because I would argue these billionaires at critical points are not going to want to have their ox gored. They’re going to be–wait a minute, enough of that, you know. And then the question is, where do you get the alternative? And I, and maybe it’s a positive point on which to end, what I like about your book Don’t Stop the Presses is you’re not a Luddite. You’re not defending the old. You’re acknowledging that there’s room on this internet to do what you really love to do. Because what we have in common, Patt–I’ll be presumptuous here, but I think what we have in common is we’ll do it whether they pay us or they don’t. You know.

PM: And they’ve taken advantage of that over centuries. [Laughs]

RS: OK. Yeah. But we’ll do it. We’ll try to get the word out, and we’ll try to, you know, speak truth to power or comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable, another great quote about the media. And you will find ink-stained wretches to do that, OK. And I do think the internet provides the space. And I think the legend newspapers are in danger of celebrating their virtue to excess. And I want to end this on one controversial note–controversial because I don’t find anybody in my circle of friends–I went to dinner last night with a bunch of people, who agrees with me? But I think we’re in danger of what I would call Trumpwashing. That we have a grotesque president, a boor, and so forth. And as a result, it gives everyone a get virtue card. [Laughs] You know, somehow, oh, if you subscribe to the New York Times, wow! Then we’re going to defeat Trump, and so forth. I have two objections to that. One, I don’t think Trump is the most effective liar we’ve had in the White House. I think he’s very effective at being boorish and crude, and we have much more opposition now in the media. I don’t want to belabor this point, but you know, my goodness, nobody ever really challenged Harry Truman on destroying hundreds of thousands of basically schoolchildren and citizens in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. No one effectively challenged Kennedy on the Bay of Pigs. You could go right down the list. The Vietnam War, the–you know, even most recently, the New York Times celebrated the invasion of Iraq, which has turned out to be one of the big disasters in our country. So I think, you know, there’s a tendency now to avoid media criticism and celebrate legend media, you know, because of Trump being so bad. And I think this is a trap, myself. And in the process, they’re actually smearing a really broad internet kind of open journalism, which I actually think is saving us. And I’m not talking about my own publication. I’m talking about that, you know, whether on the right or the left, people can get the word out.

PM: I think you’re right that there’s a lot of circulation, a lot of readership, a lot of money behind the anti-Trump audience out there. And that’s going to go away eventually; it’s going to morph into something else. The question, then, is how do these news sources, online or print, continue that support and continue that kind of consistent reporting? That’s where the loss of small-town newspapers is devastating. Because I write about in the book, one guy who won the Pulitzer a couple years ago was writing about big pharma in West Virginia, why two million doses of opioids were coming into a town of fewer than 500 people in two years’ time. What was that doing there? That’s the hard reporting that isn’t Washington, New York access, that isn’t the Trump White House, that we need to keep going. And the problem facing that–as you know, Bob, with Truthdig–people need to see that they have to pay for this kind of information. Fifty years ago, it landed on your doorstep; today, it lands on your computer screen. Somebody has to spend his or her week going out and finding out that information to make sure you get it. We should be the public’s intelligence service, but it costs money to get that. So I see that as as big an obstacle as anything else, including the disappearance of physical print, is getting people to realize that this is important. And when people say, how can I help print, or how can I help news–subscribe to the newspaper in the town where you grew up. The newspaper that covers the state capitol in the state where you grew up. That’s where a lot of the really hard work, the heavy digging, is going on. And that’s what needs the support, and that’s what’ll help to carry us through all of this long after the Trump administration ends, no matter when that is.

RS: Well, that’s a good note on which to end. And I think the saving spirit here is one of, people want to get the truth. [Laughs] You know, it’s attributed to Mark Twain and about 25 other people, a lie gets halfway around the world before the truth puts his pants on. But the fact of the matter is, you know, people do want to get it. And you know, it’s a little scary now; we have more PR students than journalism students in a lot of our major universities. You know, the cost of the profession, of sending people, covering war, covering things, is–the money’s not there, that’s a real problem. On the other hand, we have journalists in other countries writing, and you can read them on the internet; you can even translate from languages you don’t know. So really, what we need is a habit of suspicion, of inquiry, of critical thinking–and then we’re not in such bad shape. I want to thank Patt Morrison for doing this interview, but more important, for writing this book. Don’t Stop the Presses–it’s actually a beautiful book with terrific photographs. And I’m not demeaning it by saying it’s a great coffee table book, if you still have a coffee table. Truth, Justice, and the American Newspaper–Patt Morrison, with a foreword by Dean Baquet, who we know from the L.A. Times, who’s now at the New York Times. So this is a book that you want to have; if this was the Christmas season, I would say it’s a must buy, but check it out, Angel City Press, based here in L.A. And that’s it for this edition of Scheer Intelligence. Our engineers at KCRW are Kat Yore and Mario Diaz. Our producers are Josh Scheer and Isabel Carreon. And we had an able assist today from Marketplace, the studios here in downtown L.A. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.