Secrets of the ’60s Counterculture

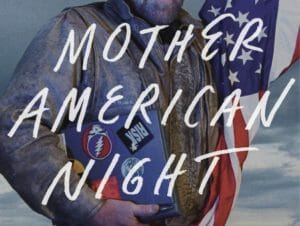

Tosh Berman, son of artist Wallace Berman, recounts his childhood surrounded by the revolutionary artists of the Beat movement. Dennis Hopper, a shaping force of the Beat generation, starred in "Easy Rider" (1969). (Columbia Pictures)

Dennis Hopper, a shaping force of the Beat generation, starred in "Easy Rider" (1969). (Columbia Pictures)

Listen to their discussion to learn more about Tosh Berman’s memoir, a book Scheer calls “a love letter to your family.”

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of “Scheer Intelligence,” where I hasten to say the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, Tosh Berman. And he’s written a book about his father, Wallace Berman, who was a very famous artist of the fifties and sixties, and here in Los Angeles. And a part of what we could loosely call the Beat movement—

Tosh Berman: Yes, Beat movement, uh-huh.

RS: The Beat Generation. And already, we’re off to an argument, because I personally think the Beats kind of, yeah, they were a little bit in Greenwich Village, but they basically—San Francisco, North Beach, that’s the Beats. And there was a hard political edge, not a consistent one, but a hard edge of rebellion, political rebellion, which I don’t think we found in la-la land.

TB: La-la land, meaning Los Angeles. OK. [Laughs]

RS: Yeah, Los Angeles. And let’s just set the scene. You were raised, you were born in 1954. This was when L.A. was the magnet for America. You know, people had come out of the military; the economy was booming. I remember it, I was the kid in the Bronx, you know, and people would get a car, pack it up, put everything on the roof, and they’d head out to L.A. I remember somebody you and I just talked about before, we called him Peanuts Cohen, Herbie Cohen—the Cohen family, Donald Cohen and Muddy Cohen, they were legendary in our neighborhood. And they were like the first to put all their stuff in a car and go to L.A. That’s—you know, you don’t see snow there, you don’t get slush in your shoes.

TB: Oh no, no snow, no slush.

RS: Yeah, no slush—

TB: Paradise, every day.

RS: —and you pick oranges off the trees. And that, you were born there, and you were born to an early rebel. And in your book, you’re at great pains to say your father, Wallace Berman—and the book does very much center on trying to get this man straight, even though you dedicate it to your mother, and you love your mother. But clearly, you have great admiration for this man, who was quite close to you, and you want us to understand him. So why don’t we just start there? What was so all-fired important about the art scene, the Beat scene in L.A., that you want to capture in this book? Which is called Tosh. And everybody knew you by that name, and all these incredibly successful, famous people—Dennis Hopper and Allen Ginsberg, Andy Warhol, Lenny Bruce, Robert Duncan the poet, Michael McClure. You were the kid running around there—

TB: I was a kid running among, I was running around among these, quote unquote, giants of culture of that time.

RS: Yeah. So what do we need to know about that Beat culture of the fifties and sixties?

TB: Well actually, you know, it’s interesting. When you look back, it’s a very set thing, the movement, like the Beat movement or the Beat Generation. But the fact is, through my eyes as a child especially, it was really just a collection of misfits of sorts. All artists, or poets and writers, who somehow did not fit into, at the time, the mainstream America at the time. They do end up in big cities, which is like New York or San Francisco and Los Angeles, as well as, you know, as Paris. Paris, France. It’s a mixture of, like, different, you know, separate individuals. Like, you could think of the Beat movement as the big three. You could think it was Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs—

RS: And I’d put Lawrence Ferlinghetti in there. And in your book, what I found, some of the loveliest, most touching points—full confession, I worked at the bookstore after I got thrown out of graduate school in Berkeley for about three years. And you really have a wonderful description of City Lights Books, which by the way is the publisher.

TB: It is my publisher. City Lights was the first bookstore I’d ever been to in my life as a child. It was my very first bookstore. So the fact that I’m published by City Lights now is this amazing circle; I mean it’s just incredibly awesome. [Laughs] I can’t think of a better word. But when I first went to City Lights, it was my first discovery of a retail store that sold something I was interested in. Because we had a lot of books at home, and my father was really good friends with Robert Duncan and Jess, his partner. And Robert’s house was full of books, Robert and Jess’s house. So this was the first time we went to a public space that was full of books; I’d never really been to a library at that point. But it was my first introduction of a bookstore as a culture, like a sort of a social place for a culture. The only thing I didn’t like about City Lights, and it was a really major thing at the time, is it didn’t have any comic books. But nevertheless, I loved the object of books; I loved how books feel; I loved the physical aspect of books. And City Lights just conveyed that sort of love of literature, and the love of the culture, and the love of the object of a book. It’s very much of a physical thing with me, as well as a textual, reading thing, as well.

RS: And for the people who haven’t been there, it’s been a big tourist destination. And you know, now, these legendary people that you hung around with, Ginsberg and Kerouac and so forth, they have streets named after them right around—

TB: Mm-hmm. I believe the alleyway right between the bar there and the—

RS: Vesuvio’s, what do you mean “the bar”? [Laughter] And Vesuvio’s, the bar, had a—still to this day, I checked out a few days ago, had this statement: “We are itching to get away from Portland, Oregon.”

TB: [Laughs] Which, oddly enough, I went to Portland the next day. [Laughs]

RS: Well, you know, Portland is actually a great town now. But what that conveyed was the rebellion against the stultifying atmosphere of the fifties, the Ozzie and Harriet view of life. You know, get the Westinghouse refrigerator, get the Nash Oldsmobile, you know, car, and you’ll have happiness. And here was a group of misfits, as you described them.

TB: Misfits.

RS: And I just want to ask you one question about, for my money, the most important of those misfits, Allen Ginsberg. And in your book, you have pictures of yourself as a kid with Allen Ginsberg. And it’s interesting, in Allen Ginsberg’s most famous poem, he begins: “America I am putting my queer shoulder to the wheel.” And people don’t realize, you know, where being gay in California, as in much of the country, was a crime until quite late. So when Allen Ginsberg wrote that in a poem, everybody knows people were arrested at City Lights for selling Howl, because it had what was called obscene language. But the use of the word “queer” then, which now is an accepted movement in human movements throughout the world—did you know that being gay was an issue?

TB: Not at all. My first gay person I ever met was Robert Duncan and Jess. And I knew as a child they were a couple, but it was before I—you know, I didn’t know anything about sexuality or sexual anything. Just, you know, I was like eight years old. But I did know they were a couple; that I did know. I didn’t know they were homosexual, gay, queer—those terms had no meaning to me at that age and time. But I definitely knew they were a couple, I knew they were like a married couple.

RS: Well, I was going to ask you about that, because that word, not “queer” but “fag,” had a lot of meaning for you when you were in high school.

TB: Yes.

RS: And you had three gym teachers—

TB: Three gym teachers.

RS: That’s an incredible trajectory. There you are, Topanga Canyon, for people who don’t know it, is kind of the idyllic Wild West of bohemians, in a way.

TB: Yeah, at the height of the sixties, especially.

RS: Yeah, and you’re with these people who were, some of them, very famous actors, writers, and so forth. Yet when you go to high school—so what year would that be?

TB: Uh, like 1968, 1969.

RS: In 1968, when we’ve had the sixties, we’ve had sexual liberation, we’ve had the Women’s Movement, we’ve had all of these things—

TB: Except for public schools, that didn’t happen.

RS: —but we didn’t have gay liberation. Stonewall comes three years, or two, three years later. And so what happened to you in junior high school? Son of a famous painter—

TB: Well, they didn’t care how famous or who he was. They basically saw me as a weirdo from Topanga Canyon. This was in Woodland Hills in the San Fernando Valley. And these three gym teachers, one was old and nice; one was kind of flirtatious to the girl students; and the third one was a total psychotic person, in my opinion. And unfortunately, I landed in the psychotic person’s class. And he hated me. Like, he hated me like when you wake up it’s the sunshine—it’s that clear that he hated me so much. And he would always make me do extra push-ups, or run extra laps, because I was never strong or never sports-oriented. I’m definitely not a P.E. or sports person whatsoever, and he resented me for that. And if I was, like, slow—you know, if I did something wrong, like something physically wrong, he would hold the whole class up ‘til I’d do it better. Like, he wanted me to climb a rope—I have a severe case of vertigo. There’s no way I’m going to climb a rope.

RS: Yeah, you don’t like to go up staircases.

TB: I don’t like staircases either.

RS: That’s in your book. But I want people to understand this moment. Because it helps explain a lot of what the Beats—and then the sixties, hippies and others—were rebelling against. That stifling conformity, and stupidity, really.

TB: Well, yes. It’s interesting, this is like ’68, ’69, sort of the height of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young; sort of even after the hippies. But yet in high schools and junior high schools, it was still a very conforming culture. And basically, you could not really have really long hair ’til very, like, probably 1970s.

RS: This is not in the Deep South; this is in L.A.

TB: No, this is the San Fernando Valley, this is Woodland Hills. And I remember, ah, one day they called me into their office, the P.E. office, they shared an office space. Why they have an office, I don’t know, I mean, they’re always outside. But they had an office space, and I knew it was a bad sign, I knew this was not good. I was there alone with three guys, three men. And basically, they just keep calling me fag this, fag that. And I’m going—at that time, I don’t even know what a fag is, really; I know it’s not a good terminology for somebody. But it was very, um—it was like, I felt like I was in the Twilight Zone. I didn’t believe I was there hearing this. Because obviously, I was in a closed room with these guys, and I felt, this is not really—one, it’s not safe, and one, it’s a little weird—it’s weird. And then they marched me to the shower, made me take all my clothes off, and as they watched me, they—I had to wash myself, I had to take a shower. I got out of the shower, and they said you didn’t get your hair wet, you have to wash your hair as well. My hair was kind of long-ish. So I said, OK. So I went there, washed my hair, and meanwhile they’re—you know, they’re verbally abusing me. Mostly the word “fag” I heard over and over again. And they never touched me; I mean, they never physically touched me or hit me of any sort. But the anger of them was something that was really off-putting, of course. But I could not figure out why they were so angry at me, and why they were doing this to me. So afterward, I think I told my parents what happened, but they didn’t do anything. Because, one, they don’t want to be involved in the school system or dealing with, you know, this issue, really, at the time. And also, it’s me against them. It was not worth it to them, it was not worth it to me to actually fight this or even—I wasn’t angry. I was just totally perturbed. And it didn’t, like, it didn’t emotionally upset me, really. But it was just a really strange incident to go through, it was just really odd.

RS: Well, but Tosh—[Laughs]

TB: Yes, Tosh.

RS: Tosh, the name of this book about the son of Wallace Berman. But think about it. Because we think we—you know, when was America great, you know? Donald Trump’s bull. Well, America was never great, any more than France was ever great, or Russia, or any other place. They always had oppression and contradictions. And it’s really interesting to think, you were in a fast-moving circle of successful people. They were rebels, but they knew well-placed, wealthy, powerful people as well.

TB: Well, yes and no. I mean, my father was a total outsider even in the art world. You know, he is a person who was kicked out of his high school, Fairfax High School, for gambling. He loved to gamble for fun and games. And then he was kicked out of high—

RS: For people who don’t know this, Fairfax is also a big public high school—

TB: In Los Angeles, yes. And people like Herb Alpert and Phil Spector [Laughs] came from Fairfax High School.

RS: Phil Spector, who’s described as kind of a maniac in your book.

TB: Yes. Yes, I met him numerous times.

RS: A big record producer, and so forth.

TB: Yeah, in my opinion, a great artist and a total lunatic, and—

RS: Did he really have a bodyguard walk behind him and say that he’ll beat you up if I just say the word?

TB: Yeah, and after my father died, he—my father had an exhibit at a gallery, and he was there at the exhibit, at the opening. And he was with a bodyguard, this big guy. And he was going up to total strangers—just going up to them while they were talking—and saying, he’d just go, excuse me, but if I wish, I could have the guy behind me just beat you up.

RS: You know, we’re going to run out of time if we don’t move this. But let me just—what wisdom did you get from being at the center of an L.A. art world that has produced very famous people, right? Ah—

TB: They were not famous at the time, though, and it was not really a money issue or a power issue at that time. It was more art for art’s sake. All these people are—

RS: Was that true of Andy Warhol also?

TB: Oh, absolutely, in my opinion, yes.

RS: Tell me about Andy Warhol, because he emerges later as a very successful hustler as well as artist.

TB: I think he was a great artist, but he was a hustler as well. And they go hand-in-hand sometimes. I think, you know, Warhol came to Los Angeles to make a movie, Tarzan and Jane Regained. … Sort of. It was an early Warhol feature. And my dad was in it, he played the white headhunter, and Taylor Mead played Tarzan. And since I was the only boy there, I played Boy, Tarzan’s son in the movie.

RS: You were in a number of movies, right?

TB: I’ve been in, like, underground cinema. And you know, I had a chance to be in Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, but I turned it down. Which, I made the movie better for that reason, I think I contributed greatly to Easy Rider and its success by not being in it. But you know, but at this time, everybody was struggling at the time. It wasn’t like, nobody actually made it; everybody was just maybe about to make it, or they’re going back and forth about to make it. And my father was very much in the art world, but he was not really part of it, as well. You know, he worked differently from other artists.

RS: Describe his achievements, his artwork, for people who might not know his name.

TB: My father is considered the father of California assemblage art, which is using collage sculpture. I don’t think that’s the right definition, but he’s known [for] that. And then he started making collages, photo collages, using the Verifax copy machine, which is a wet-process copy machine that was used in offices during the sixties. And he altered the chemicals; in a way he made his own dark room. So it became like his campus, his dark room, and making photos, but doing collages. And the key singular image that my father is famous for is a hand, a singular hand holding a transistor radio, like a Sony radio, and there’s images inside the radio. And he has made individual pieces that way, and he also made pieces that were sort of grid-like. And the grid-like pieces, for some, is very similar to Andy Warhol’s early, early work. And they didn’t influence each other; there’s, you know, it’s just, those things were in the air at that time.

RS: But he had his successes. He made record album covers—

TB: Well, that’s—he made, as a teenager he made a drawing that became the cover of an album called Be-bop Jazz, and that was the first album, or first ’78 that Charlie Parker appeared on. It was a compilation, and Charlie Parker first appeared on that record. And my dad made, did the cover for it.

RS: Yeah. In fact, he flirted with success. He decided at a certain point, he’d had a bad experience with a commercial gallery, and he said I’m not going to do this anymore.

TB: Right, he did.

RS: And so one thing we have to give credit to this group of people is they were battling over not selling out over integrity.

TB: My father never compromised. He did always what he wanted to do in his art. Never, ever, ever, ever compromised.

RS: And that was in the air. And it stayed there through the sixties, don’t sell out, and so forth. Our students—we’re recording this at the University of Southern California, and if I mention that to my students in class tonight, the general response will be “easy for you guys to have said that.”

TB: Right.

RS: There was a lot of opportunity then, the economy was booming.

TB: Well, the economy was booming for people who were in the system. But if you were outside the system, it was very chancy. I mean, I was not raised as a wealthy—

RS: I know, but just as a little footnote, when I came to Berkeley in 1959, I rented the cottage in the back of a place that Allen Ginsberg had been living in. My rent was fifty bucks a month. Now, even given the appreciation of the dollar, the fact is you could live a bohemian life. You lived on a boat in—

TB: A houseboat, yeah.

RS: You lived up in Topanga Canyon—you couldn’t live in Topanga Canyon now.

TB: No. And basically, in those—there were cabins, it was a cabin in Topanga Canyon.

RS: Yeah. You know, and there was room—room for this kind of alternative lifestyle. Now you’d have to be living in a cardboard condominium on Spring Street in the rain, you know, as a homeless person. So I’m not putting down their spirit, but I think there was a strong spirit, that you could be independent and still have a good life.

TB: They had no choice. My father had no choice except to be independent. There was no question that he could compromise to the mainstream culture of that time. He just could not do that.

RS: So tell me what you’ve learned about the art world, and then I have to take a break. Because some of these people went on to be very wealthy, and very successful. And they speak admiringly of you; they knew you as a young man.

TB: Yeah. Wealth—you know, wealth is, to me, is—to me doesn’t mean successful. Wealth means they have money, and that’s it. And they lose money. So wealth doesn’t mean anything to me, personally. Basically, the art world at that time was very cottage-like, was very small-town like. Like, Ferus Gallery, which was my dad’s first gallery and last gallery, was a very prominent gallery in Los Angeles. It was a gallery that had Andy Warhol’s very, very first solo show in Los Angeles. But also, he didn’t have a solo show in New York ‘til he came to Los Angeles. And it had people like Ed Ruscha, Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, and then I think even Rauschenberg from New York had shows. You know, in the sixties, late fifties and in the sixties. So it was a very much—everybody knew each other, and it was very much of a small-town community, really. There was art school, but there was no, like, art school theory; there was no, like, studying under and artist and follow that artist’s blueprint of being successful, or being successful, or getting a gallery. It was more of like a Wild West town; it was more like you’re on your own, but you had friends who would help you. And you, in turn, would help them as well.

RS: Yeah. And your book, the book is Tosh, City Lights Books. And it’s wonderful to read. First of all, you know, I’ve got three sons; I wish they would write a book about me someday like this. [Laughter] No, it’s a love letter. It’s a love letter to your family, to your mother and father. And to the people around them. And they deserve it, I think. As somebody who passed through their world, I think it’s an accurate and extremely well-written book, by the way.

TB: Oh, thank you.

RS: [omission for station break] I’m back with Tosh Berman, the author of Tosh, a terrific book centered around his father, who was a very famous Los Angeles artist. But really, about a time that you want to know about, because it’s when art mattered, when it wasn’t done for billionaires, when it wasn’t dependent upon kissing the tuchus of people who own big galleries or sit on big art boards. These guys, they were the Wild West, as writers, as graphic artists.

TB: Truly were.

RS: And so I want to ask you about one painting in particular that’s in your book, Tosh: “Fuck Nationalism.”

TB: Yes! That’s my dad’s politics in a nutshell. It’s basically a drawing done on a negative, like sort of a Verifax collage, early Verifax collage, where he had handwritten “Fuck Nationalism.” That was my dad’s politics, really. He didn’t really, he was not really concerned about—if he was alive now, he’d probably be more likely to be a social libertarian than anything else.

RS: That’s your dad’s politics. But tell us what that drawing was all about.

TB: I think it’s basically about his life in the fifties and the sixties. He did not like institutions, he didn’t like cops, he didn’t like authority, he didn’t like the justice system, he didn’t like the government, he didn’t like any government. He didn’t like nations, he didn’t like orders. He never joined a political party. I don’t believe he ever voted. But he did give money—or not money, but he donated artwork to raise money for people who were resisting the draft during the Vietnam War. So he did participate in actions against the Vietnam War, and certain other social causes of that time. But he never actually marched in a demonstration or held a banner or participate in the political process at all.

RS: But let me, the reason that caught my eye in your book—the book is Tosh, a memory of Wallace Berman and the whole wild crowd of, let’s call it Los Angeles Beats—that was drawn in what year?

TB: I believe like 1959 or 1960—1960, probably.

RS: And a couple of years later, not very many years later, Paul Krassner of The Realist magazine came out with a red, white, and blue poster with stars on it. And it said “Fuck Communism.”

TB: Ah.

RS: And the great thing was, you know, people were arrested at City Lights Books for using that word. Yet the very people that harassed you, and made you take the shower, probably thought hey, that’s a good sentiment! I’m not going to throw a kid out of school for that!

TB: Yes. No way.

RS: And the money made from that poster—I love telling this story, so let me tell it for the umpteenth time—was money that paid for my ticket to go to Vietnam to write about the war in ’64 and ’65.

TB: Oh! Oh.

RS: Paul Krassner, because he made so much money from selling that poster. But I didn’t realize until I picked up your book that the idea might have come from your father.

TB: That’s the great thing about the sixties. You know, again, it is a small cottage. The political world, the radicals of the time, and the artists. You know, it’s just a small world. So things like that were easily picked up. My father, for instance, read the Village Voice when it was a great paper, from the first page to the very last, including all the ads—everything. He read all the so-called, quote unquote, underground political press, as well as like the Los Angeles Free Press, and all the alternative papers of that time.

RS: So I want to ask you, ah, about Ginsberg, Allen Ginsberg. I once wrote an essay in a little magazine called Root and Branch, saying “Poet is priest.” And it was a celebration of Ginsberg as a free spirit, as an anarchist thinker. And it was, my criticism was of the left, that leftists will become bureaucrats and strangle thought, but Ginsberg has got hold of a very powerful idea. So tell me, was I wrong to be this high on Ginsberg? You knew him through the eyes of, what, an eight-year-old?

TB: Eight-year-old. Allen seems to be the one—well, first of all, even as a child, he was extremely famous. People recognized him on the street. I remember going to London, we were in London in the Summer of Love, June 1967. And I remember, like, we were in an Indian restaurant, as a child, like 12, 13, we were in an Indian restaurant and there were these two women wearing traditional Indian clothing. And they were speaking their own language, but once in a while you heard the words “Allen Ginsberg” coming out of their mouths. And Allen, to me, was incredible at public relations, as well as being a great poet. He was the one who took the responsibility of trying to convey a political message or a social message—more than say, like, Jack Kerouac, who was not really that political—

RS: To a degree, he was. He was actually, would probably be a Trump supporter now. He was the angry white male.

TB: Yeah, and I’m not surprised, I see that in On the Road. See, the thing about the Beat Generation is not everybody’s the same. They’re all, like, totally different from William Burroughs; Burroughs is totally different from Ginsberg. You know, these are individual writers that were—they met, they became friends. But even politically, I would not say they agree on, you know, on the same policies.

RS: No, and for instance I have interviewed, I’m very close to Ferlinghetti, who’s now celebrating his hundredth birthday. And he was a guy who was politicized as a commander in the Navy of an anti-sub boat, and he saw the horrors of war, he went to Nagasaki and witnessed the effect of the dropping of the bomb. And always was a very committed, after that, pacifist. And took his political views seriously, which I do think Ginsberg did as well.

TB: He did. But somebody like, obviously, William S. Burroughs has the sort of more darker side of the Beat thing. And then Kerouac is sort of like a conservative soul, and a very much—that’s who he is. You know, he’s not a radical, he’s not left-wing. He’s a classic American author who somehow became part of the Beat movement, or the head honcho of the Beat Generation.

RS: Well, because he had anger that some Trump supporters have. Let’s bring it to the present. Kerouac’s sitting there in Long Island, I forget where, West Islip or someplace, and he thinks the country’s going to hell in a handbasket for very different reasons than Allen Ginsberg thinks.

TB: Yeah, didn’t like commies. [Laughs]

RS: No! And he probably didn’t like most people who lived in New York City for one reason or another.

TB: I don’t know about that. But he didn’t like commies; he didn’t, he was for the war, I believe, in Vietnam. Or at least, I think his mind was for the military. He was probably for the soldier. I don’t think he thought that deeply about the war, or the issues of the Viet Cong versus the U.S. I think he was basically like, you got to support our troops, right? You got to support the troops, no matter what. And I think he took things on that very surface level, because he’s a guy who dealt with symbols. You know, get in the car, go cross country—you know, that’s such an American thing. You know, get on the highway and just go west, or go—gee, I want to have a cup of coffee, let’s just go across the country for a cup of coffee, type of thing.

RS: So finally, because we’re going to have to wrap this up, let’s talk about the end, with the big message of this book. I think it’s a very valuable book. Because it tells you about the possibilities of free thought, creativity, independence of spirit, within an otherwise conforming, materialistic, capitalist society. These people knew the game was rigged; they knew there were powerful interests, powerful forces. As you say, with Kerouac, he was coming from a more right-wing critique; Ginsberg’s coming from a more left-wing, progressive. But they all knew that America, as it was constructed, was a place of possibility, yes, and they were going to seize those possibilities—but it was far from, forget about being a perfect world, it was far from being a very interesting world. It was boring in many ways. It was overrun by advertising, by consumerism. And they were crafting—in fact, this one scene, I forget who’s buying you a hamburger, doesn’t want to buy you a hamburger—

TB: Michael McClure. He wouldn’t allow me to have a hamburger. He was in a French restaurant that was very elegant, very French, and I just wanted a hamburger.

RS: But the damn thing was, these guys cared about French writers, you know?

TB: [Laughs] Yes, he did. And my father idolized and loved French surrealism and the Dadas, and 19th century Charles Baudelaire, Rimbaud; my dad, that was like my dad’s food. He loved it.

RS: Right, and then you had Kenneth Rexroth celebrating Chinese culture, and others celebrating Indian culture, like Kerouac. So it wasn’t just white Europe that fascinated them. So here you have this, dare I say, band of merry pranksters; they’re in L.A.; and you didn’t like my using la-la land, but—

TB: Los Angeles, please. [Laughs]

RS: Yeah, but this was the old, you know, L.A. You know, L.A. that—in the mind of people outside the country; we know there were a lot of people living here who weren’t like that. And it was the center of imagining America as a consumerist, boring, you know, wealthy society. And you had these rebels here, and that’s what Tosh is about. If you want to read about people who gave the finger to that world of Hollywood, and actually did it within Hollywood, knew a lot of the players, influenced mass culture—

TB: There’s people who are like bridges, and Dennis Hopper was a good bridge between old studio Hollywood, and new Hollywood of course, but also the art world, the avant-garde art world. Hopper was a really unique person, that he was somebody in both worlds comfortably. He was very comfortable in the art world, the avant-garde world, but he was also comfortable in the old Hollywood studio system, which was dying out at that time. So he became one of the inventors of the new Hollywood, due to Easy Rider, and then with the same producer who did Easy Rider, also did Five Easy Pieces, and so on and so on. You know, Jack Nicholson came out of all that.

RS: Yeah, and Warren Beatty.

TB: Warren Beatty. And—but the original money of all that came from the fab four, the Monkees. The Monkees made the money [so] that Easy Rider could make the movie. And because Bob Rafelson, who produced the Monkees TV show, when the Monkees became successful they put the money into their own production company, gave money for Easy Rider, and then Five Easy Pieces, and so forth.

RS: So one last story to wrap this up. Tell us how Bob Dylan met the Beatles.

TB: [Laughs] Well, I wasn’t there, I wasn’t in a suitcase. But Al Aronowitz is a noted journalist now, or well-known. But at the time, my dad met him in the late fifties. And Al Aronowitz was working for, like, a mainstream New York publication.

RS: The New York Post.

TB: New York Post. And he was interviewing all the Beat personalities, including Kerouac, Ginsberg, and so on. And he did an interview with my father, which my dad never does an interview, but somehow he just was weak that moment, and he agreed to do the interview. After the interview was over, and after he left, my dad decided, I don’t want to be interviewed by him. So he located him in his motel, hotel, whatever, barged into his space, took his reel-to-reel tapes and destroyed all of them, including the Jack Kerouac and the Ginsberg interviews of the late fifties. Strangely enough, you’d think Al Aronowitz would be really pissed off at my dad, and they’d be lifetime enemies, but they became very close friends afterwards. So Al Aronowitz is the first guy who introduced Bob Dylan—he brought Bob Dylan to meet the Beatles in the Beatles’ hotel, and introduced marijuana—pot—from Dylan’s and Al Aronowitz’s world to the Fab Four. The Fab Four were not innocent; they were drinkers, and also I think did amphetamines, you know, they were taking pills to keep active and keep going at that time.

RS: So let’s leave it at that. The book is Tosh, published by City Lights Books. And it’s a terrific read. That’s it for this edition of Scheer Intelligence. Our engineers at KCRW are Kat Yore and Mario Diaz. Joshua Scheer and Isabel Carreon produced the show. And Sebastian Grubaugh here at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism held it all together.

TB: I just want to thank everybody. Thank you so much. I really—I don’t want to leave, but I can see I have to go. But thank you so much. [Laughs]

RS: Yeah, well, you’ve left a book, and we can all enjoy it together. Take care.

TB: OK, great. Thank you so much.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.