Frieze L.A. Looks Good for Galleries, but Artists Give Mixed Reviews

The Los Angeles art fair raises questions about the effect gentrification is having on artists and collectors. The Paramount Studios backlot is a hot spot for art enthusiasts attending Frieze Los Angeles. (Jordan Riefe)

The Paramount Studios backlot is a hot spot for art enthusiasts attending Frieze Los Angeles. (Jordan Riefe)

As Frieze Los Angeles takes center stage at the Paramount Studios backlot this weekend, the arts community is of two minds about the arrival of one of the world’s most prestigious art fairs. “L.A. has great galleries, both established and young, and fantastic institutions. It has world-class art schools, [it’s] a place that artists choose to live and work. The only thing it doesn’t have is a major art fair, and we’re bringing it with Frieze,” Victoria Siddall, director of Frieze Fairs, told Truthdig.

But the recent past is littered with art fairs that launched in Southern California with great fanfare, only to sputter out. In the same location Frieze inhabits through Sunday, Paris Photo L.A. closed in 2016 after only three years. During the same period, FIAC (Foire International Art Contemporary) scrapped plans to launch an L.A.-based fair, pointing to a lack of interest and buyers. Indie fair Paramount Ranch also closed in 2016 after three years.

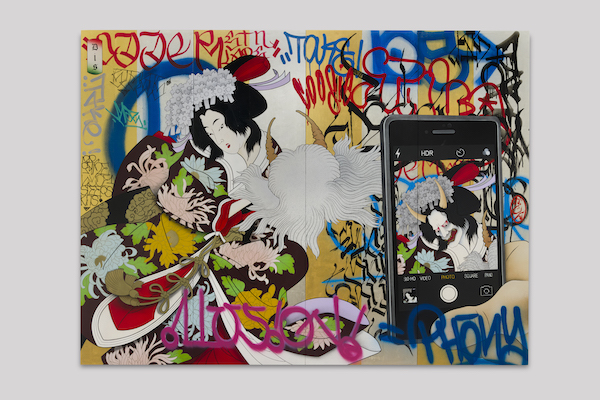

But Frieze L.A. might be charmed. During a biblical deluge Thursday morning, the show blithely carried on, with works going for substantial sums before the preview day was done. Hauser & Wirth sold Mike Kelley’s “Unisex Love Nest” installation for $1,800,000. Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Nets (B-A-Y)” fetched an asking price of $1.6 million. L.A. Louver sold three of five works by Gajin Fujita at $40,000, $45,000 and $250,000. And a 1967 work on paper by Alexander Calder went for $200,000.

“It’s about timing and about money,” said Kori Newkirk, whose “Signal,” a series of sculptures made from TV antennas occupies the New York street on the backlot, along with installations by such blue-chip names as Paul McCarthy, Barbara Kruger and Sarah Cain. “We’ve had so many flashes before. Maybe it will be a big flash at first, but then it becomes sustainable. Maybe this is the right time for this to happen, and maybe because the machine has gotten behind it in a way that something can happen. We’ll see.”

Some 70 exhibitors, including such big names as Gagosian, David Kordansky, David Zwirner, Blum & Poe and L.A. Louver Gallery, are presenting new and recent work by a who’s-who of living artists, including Doug Aitken, Fujita and Judy Chicago.

Legendary L.A. artist Billy-Al Bengston, who is not participating in Frieze, is unfazed by past failures and future prospects for a major fair in L.A. “I don’t even know what the fuck it is. If it’s a fair, that’s for judging horses and things like that,” he quipped. “That’s for the Hollywood celebrities. It’s an industry; you have agents who sell you and so forth. It’s an advanced whorehouse. My stilted feeling is it’s only for the cognoscenti anyway, or the well-informed. If you start selling to everyone, you’re pleading for public. What you should be pleading for is a higher aesthetic ground.”

While the art world has traditionally looked to New York and Western Europe for influences and trends, the 2011 landmark show, “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1940-1980,” featured works by Bengston, Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha and other members of the “cool school” artists who got their start with the city’s famed Ferus Gallery in the 1950s. The show put the art world on notice, highlighting the city’s singular midcentury contributions.

At Jeffrey Deitch’s booth at Frieze Los Angeles, Judy Chicago will be showing early works, from a time when she struggled to be one of the boys at the Ferus Gallery until she decided to focus on what made her different from the others and became a leading figure in feminist art, establishing the nation’s first feminist arts program at California State University, Fresno, in the ’70s. Her most famous piece, an installation called “The Dinner Party,” is a part of Brooklyn Museum’s permanent collection.

In recent months she’s been having a moment, with a career retrospective at ICA Miami in December and a retrospective of early works at Jeffrey Deitch’s space in Hollywood set for the fall.

“I’m very opposed to the way the art market has taken over the art world,” Chicago said by phone from her home in Belen, N.M. “I had the privilege of making art for five decades without thinking about the market. But now that I’m old—and it’s not possible to be old and poor in America—I’m thinking about the market. John Baldessari said that artists going to art fairs is like watching your parents have sex. It’s not a good thing to do.”

While artists benefit from fairs like Frieze Los Angeles, gallerists are the true beneficiaries. Los Angeles County Museum of Art President Michael Govan thinks many of them have opened an L.A. branch not because buyers are there, but because artists are, and it behooves them to have a presence. Yet a fully developed art market, such as the nation’s largest, in New York City, has done little to stem an exodus of artists seeking reasonable rents and enough space to do their work. In recent years, that city has seen billionaires push millionaires from Manhattan to Brooklyn, while the millionaires pushed the artists to the West Coast. And now the same thing appears to be happening in L.A.

“I don’t know if an art fair will necessarily change that,” Newkirk muses. “That would be great. But the real estate thing, yes, I see it around my studio, which is downtown. I see it around my house, which is downtown. I see it around everywhere, and I worry for myself and everybody else.”

Lifelong L.A. artist Doug Aitken just unveiled “Don’t Forget to Breathe,” a storefront installation in a Hollywood strip mall, timed to coincide with new works he’s showing at 303 Gallery’s booth at the fair. He’s famous for a mixed-media practice that includes “Electric Earth,” a multiscreen experimental short film about the last man on earth, and “Mirage,” a mirrored house in Southern California’s high desert, copies of which he has placed in Detroit and more recently, in Staad, nestled in the Swiss Alps.

“In many ways, the idea of an art market—it’s almost tertiary to the art itself that’s being made, which is really what matters,” Aitken says. “If there’s a market or not, I think the artists are going to continue to push limits and provoke. In some ways the idea of the market is superficial to the art itself.”

While it’s true that no amount of money can snuff out the creative impulse, “they can snuff out my ability to have a sustainable practice, because I can’t afford to work and live here,” Newkirk says, adding that he is considering leaving the area. “Las Vegas, Long Beach, anywhere. I have my next-to-be-gentrified neighborhood picked out. So, if there’s any speculators out there who want to support me in that. …”

Raised on L.A.’s East Side, Fujita spent his formative years tagging walls with such crews as KGB (Kidz Gone Bad) and KIIS (Kill to Succeed), but has since distinguished himself with large-scale works combining Japanese motifs with L.A. street style. He’s been around long enough to recall what the downtown Arts District used to look like, before real estate prices started to rise.

“When I was going there in the ’80s, it was nothing. It was piece of shit—Al’s Bar across the street and the American Hotel was fucking run down as hell,” Fujita recalled. “I rented a studio with my friend there in ’93, right above Al’s Bar, but it was dingy and grimy. But now—I was there recently. There’s restaurants and bars, and fucking Hauser & Wirth moved in there. Jeez, wow!”

Fujita is represented by gallerist Peter Goulds’ L.A. Louver in Venice, Calif., which also reps David Hockney. Goulds established the gallery in the 1970s. An eyewitness to market convolutions over nearly 50 years, he remains unfazed by hopes and expectations surrounding Frieze Los Angeles.

“These fairs are cyclical. There’s too many today, so they’ll inevitably fail, and will continue,” he observes. “The oldest art fair is barely in existence—that’s the Cologne Art Fair. No one even talks about it. Chicago was the most important fair in the ’80s, no one talks about it. Basel was moribund in the ’80s, now it’s the big deal. Well, it won’t always be.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.