Residential Racism

The author examines 'Sundown towns'—all-white communities that kept out minorities with laws, threats and violence—in the context of Trump era racism and #BlackLivesMatter. Touchstone

Touchstone

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

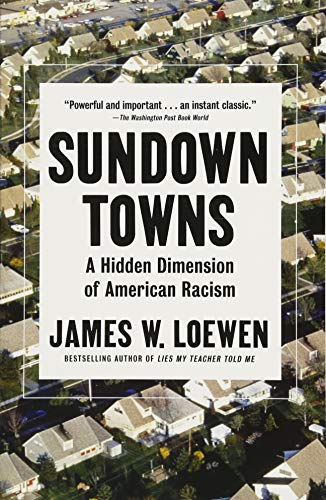

“Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism,” 2018 Edition

A book by James W. Loewen

Racism has despoiled our nation from its very inception. Slavery and Jim Crow have killed, maimed and degraded millions of human beings of African descent for centuries—a tragic legacy that continues, sometimes overtly, sometimes more subtly, into the early decades of the 21st century. Almost everyone knows the major features of this sorry history. Students who suffer through the distorted and inadequate history that this book’s author, James Loewen, chronicles in his magnificent “Lies My Teacher Told Me” usually learn at least something about American racism, even while they fail to learn many of its grimmer details.

In this 2018 edition of “Sundown Towns,” an update of his groundbreaking 2005 version, Loewen fills in some of the gaps of public ignorance. His findings are appalling. He reveals that racism in America has been even more pervasive, more systemic, more geographically widespread, and therefore more grotesque than most people—even many progressives and well-meaning anti-racists—could ever imagine. The narrative in this supremely important book is chilling. It is essential to fully comprehend that, despite the formal end of segregation and the advances of the modern civil rights movement, racism has pervaded the entire fabric of American life.

Click here to read long excerpts from “Sundown Towns” at Google Books.

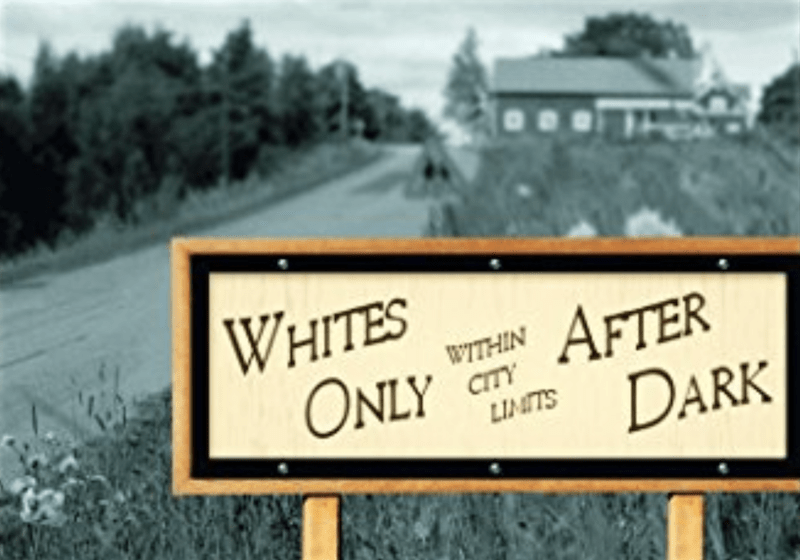

Loewen pulls no punches in the preface to his new edition: “[S]undown towns kept out African Americans. Some excluded other groups, such as Mexican Americans, Native Americans, or Asian Americans, Jews, even Catholics, and Mormons. These places get called ‘sundown towns’ because some, in past decades, placed signs at their city limits typically saying some version of ‘Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on You in [name of town].’”

Loewen’s new edition locates the history of sundown towns in the context of contemporary events, with the resurgence of racism in the Trump era and the resulting increase of overt white supremacist rhetoric and activity, but also with more energetic African-American resistance including the Black Lives Matter movement. In this edition, Loewen has augmented his earlier research. He concludes that sundown towns are declining, but despite some progress, residential exclusionary practices in the United States remain a fundamental feature of institutional racism.

Since Loewen began his initial work, he has maintained an active research interest in the topic, including a website and a database of all the sundown towns he has been able to document. This is a remarkable resource for scholars, activists and laypersons alike.

The present book documents the “second generation” sundown town phenomenon. In the author’s home state of Illinois, by his estimate, there are still 507 sundown towns—two-thirds of the towns in the state. The new section of this remarkable book documents the recent developments in these segregated residential communities throughout the U.S. Fortunately, sundown towns are declining, suggesting a slow but steady change in the attitudes of the dominant white population in America.

Still, workforces in former sundown towns even now reflect the residual racism of the earlier exclusionary residential policies: Police officers, teachers, trash collectors and other jobs remain all or predominantly white. The ideology of white supremacy lingers, sometimes strongly, even while a few people of color begin moving into these towns in the 21st century.

As Loewen notes, racial jokes and invective remain. Black children especially feel isolated in largely white educational settings, where the curriculum remains Eurocentric and little or no treatment of African-American history and culture is available. Even more troubling, patterns of law enforcement continue the long and dishonorable pattern of racism. “Driving and Walking While Black” remains common; African-Americans continue to be targeted for minor traffic and other infractions in these formerly sundown towns. The former sundown town of Ferguson, Missouri, became internationally notorious, culminating in the egregious murder of Michael Brown in 2014. Racial profiling is all too alive in these locales and remains a powerful source of dread among African-Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities.

The majority of “Sundown Towns” involves the hidden history of this disgraceful phenomenon. Loewen’s point is striking: Until he published the first edition of this book, there was almost no literature about all-white towns in the United States. Of the relatively few people who knew anything about sundown towns, most probably thought it was a Deep South phenomenon. It was not. This book documents hundreds of non-Southern towns that for decades excluded blacks from living within their limits. Many were well known, including towns where many famous American writers, entertainers, politicians and other celebrities lived and worked. Some were small, with as few as 500 residents, while others had well over 100,000.

The author asks many powerful questions in this volume, most notably why these towns have excluded blacks and other minority groups for so long, and why some still persist. We have made progress in certain areas of race relations in this country—in education, employment, some areas of politics and elsewhere. Although there has been some notable judicial backsliding in recent years, especially in voting rights and affirmative action, legal decisions have largely advanced civil rights since the mid-20th century. Legal segregation in schooling and elsewhere was ended with major Supreme Court and other rulings. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court in Shelley v. Kraemer explicitly ruled that restrictive racial covenants in housing could not be enforced. Fair housing laws are widespread throughout the nation. But informally, with the discriminatory practices of many real estate companies and agents, and perhaps developers like our current president, blacks have been excluded from all too many towns in the United States.

The deep-seated attitudes of white supremacy need to be faced directly. Millions of white Americans are willing to go on public transport with black passengers, eat in restaurants with black customers, send their children to school with black students, work with black colleagues, and do many other daily activities with black people. But they draw the line at having black neighbors; sometimes this is overt and sometimes it is unconscious, unacknowledged. In either case, it is profoundly racist and leads to the creation and perpetuation of sundown towns.

The substance of the 2005 edition of”Sundown Towns” provides cogent historical and sociological analyses of this hidden feature of American racism. Loewen shows, for example, how, in the era after Reconstruction, during the height of Jim Crow from 1890 to 1940, about 15,000 towns and suburbs went sundown. This was the “Nadir Period.” Still, 80 percent of all suburbs remained sundown well beyond that time frame.

Among the most brilliant—but appalling—parts of this book are Loewen’s accounts of the horrific acts of brutality that whites have committed against African-Americans and other “undesirables.” They reveal just how calculated white people have been to create and preserve their racially pure domains. The Ku Klux Klan, one of America’s oldest domestic terrorist organizations, has often perpetuated this violence. The Klan, as Loewen indicates, has found fertile recruiting grounds in sundown towns over the years, even at present. But most violence against blacks and other minorities have emerged without assistance from outsiders. When African-Americans finally managed to move into formerly all-white neighborhoods, residents themselves often resorted to threats, then actual violence.

“Sundown Towns” accounts a phenomenon that touched me personally and fundamentally informed the entire course of my life. Loewen examines the creation of the three white-only Levittowns in New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, begun in the early 1950s. Levitt & Sons, the largest postwar homebuilder in America, built 8 percent of postwar suburban housing—all sundown. The Levitt organization, headed by William Levitt, publicly and officially refused to sell to blacks. Levitt, himself a Jew, had earlier used restrictive covenants to ban Jews from developments he built. As he noted, “[i]t was strictly business.” Actually, it was strictly capitalism, a major incubator of racism.

My parents moved to Levittown, Pennsylvania, in the mid-1950s because housing there was affordable for a growing family. Unaware initially of its sundown status, my parents soon became aware of Levittown’s racism. They joined a few other families who met and conspired to help the first African-American family desegregate the town.

I was the oldest of four children and tagged along to the meetings before the first African-American family, Bill and Daisy Myers and their children, moved in on Aug. 17, 1957. They and their supporters, like my parents (and me), faced hostile racist mobs, death threats, vandalism and horrific harassment from neighbors. For weeks, these mobs gathered in front of the Myerses’ home, shouting racist epithets and making crude gestures. I witnessed the twisted face of bigotry at a young and impressionable age.

In September, we woke up to a large burning cross on our lawn. In December, I testified in a trial. The attorney general of Pennsylvania, Tom McBride, conducted the trial, though it was rare for the highest state legal official to serve as a trial attorney. I was 14 years old. McBride told me to only tell the truth, and not be afraid. I remember his compassion and consideration well. During the trial, I identified the head of the local “Betterment” committee, the organization that sought to rid Levittown of its first African-American residents. In open court, I testified that the Betterment Committee’s James Newell had called me a “nigger lover,” one of many hundreds of times that that repulsive appellation had been hurled at me during the Levittown crisis, and that on numerous nights, a motorcade, flying Confederate flags, would roar past our house.

The courageous Myers family weathered the racist storm and stayed, formally breaking the back of Levittown’s sundown status. I have written and taught about my experience as a young teenager for many decades. I have also given several oral histories about my experiences in Levittown. It catalyzed my life as a civil rights activist in the South, and in California and adjacent areas. It also fundamentally informed my work as a university teacher and as a writer and scholar. My early sundown experience made me a fervent anti-racist for life.

Loewen’s book features many of these real-life stories of sundown towns. Like all exemplary histories, it addresses the human realities that readers find especially engaging. These first-person accounts are crucial in understanding the horrific effects of sundown towns on all residents, white and black alike. The volume also contains a substantial photographic section. The pictures are difficult to view. They contain images of lynchings and egregious racist language, but they are necessary to come to grips with this nation’s horrific racist past.

“Sundown Towns” ends with a comprehensive three-point program for local institutions, students and citizens in general to alleviate the continuing problem of residential racial segregation. He titles the final chapter, “The Remedy.” I admire his resolve; it is an especially valuable addition to this outstanding book. Still, like the late Derrick Bell and a few others, and after a lifetime of civil rights activism and teaching, I have concluded that American racism is intractable. Anti-racist action, however, is always desirable.

James Loewen is a national treasure. His works have alerted thousands of readers to the multifaceted existence and dangers of racism and other problems in America. “Sundown Towns,” like all his books, reflects the finest progressive and critical tradition of American scholarship. I take enormous pleasure in recommending them to my students. Trained as a sociologist, Loewen is really both a sociologist and a historian, working in the magnificent tradition of C. Wright Mills and Howard Zinn. I can offer no finer recommendation for this book.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.