Ultra-Deep Life Forms May Survive Climate Change, Even If We Don’t

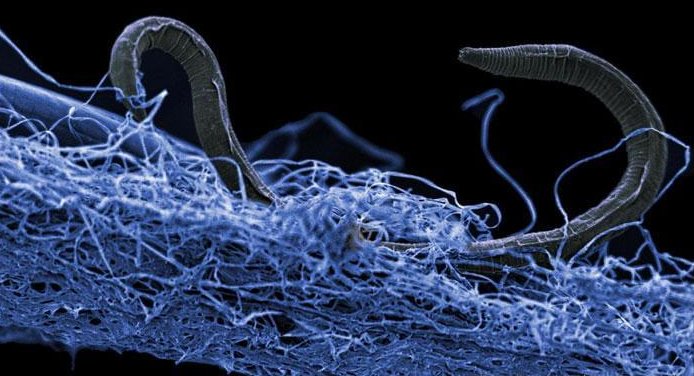

Even in the worst climate scenario, this huge and diverse community of living things may ensure that life as we now know it continues. This nematode lives far below the earth’s surface in South Africa. (Gaetan Borgonie / Extreme Life Isyensya, Belgium)

This nematode lives far below the earth’s surface in South Africa. (Gaetan Borgonie / Extreme Life Isyensya, Belgium)

Microbiologists have good news for those who fear that runaway global warming could disrupt human civilisation, trigger a sixth great extinction of animal and plant species or even start to wipe out most of life on Earth. Even in the worst case, ultra-deep life forms may ensure that is not the end of life as we now know it.

New research confirms that far below the continental surface, at depths of 5km or more, and 10kms below the highest ocean waves, there is a huge and diverse community of living things, seemingly isolated from any climatic disruption and oblivious to catastrophic drought or flood, global thermonuclear war or even asteroid impact.

This community of deep-dwelling single-celled creatures is enormous: bulky and crowded enough to outweigh the mass of the seven billion human beings on the planet by a factor of at least 245, and perhaps as much as 385 times. They have immensely slow life-cycles: they have even been called “zombie” microbes.

Altogether, the mass of archaea, bacteria and eukarya – the three main stems of the tree of life – to be found in the deep Earth adds up to at least 15 billion and possibly 23 billion tonnes.

Rock colonists

Carbon-based life forms that, 20 years ago, no one could be sure existed, are thought to have colonised porous rock and buried sediments in a separate biosphere space of 2 billion cubic kilometres: a volume far greater than the world’s oceans.

Researchers involved in a co-operative called the Deep Carbon Observatory revealed these astonishing figures at the American Geophysical Union’s autumn conference in Washington, D.C.

“Exploring the deep subsurface is akin to exploring the Amazon rainforest,” said Mitch Sogin of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole in Massachusetts, who chairs the Deep Life community of more than 300 scientists in 34 countries.

“There is life everywhere, and everywhere there’s an awe-inspiring abundance of unexpected and unusual organisms.”

“Scientists do not yet know all the ways in which deep subsurface life affects surface life and vice versa”

Estimates of carbon-based life are important in climate calculations: researchers are still trying to calculate with a degree of accuracy the seasonal traffic of carbon between living things, rocks, ocean and atmosphere.

But the same estimates are vital in simply understanding life’s complexity: earlier this year, US and Israeli researchers published a comprehensive assessment of the distribution of carbon between living things on the planet’s surface: trees, herbs, grasses, fungi, microbes, vertebrates and so on.

But all surface creatures breathe air, consume rainwater and absorb energy that comes primarily from the sun, via photosynthesis. It was only in the last years of the last century that researchers began to confirm a strange, unexpected but rich biosphere far below the surface: composed of microscopic creatures that gain their energy from the heat of the deep crustal rocks, live on nutrients from the chemistry of the planet’s minerals, and flourish in conditions of almost unimaginable temperature and pressure.

Researchers have found microbial communities in deep submarine coal mines off the coast of Japan, in slabs of submarine basalt, below oilfields, in the deepest hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the deepest oceans.

Just surviving

Microbes have been found surviving at temperatures of 121°C and at atmospheric pressures 400 times greater than those at sea level. And, like life on the surface, these creatures exhibit diversity: they may be as various or even more diverse than lifeforms that dwell in the sunlight and air.

“Ten years ago, we knew far less about the physiologies of the bacteria and microbes that dominate the subsurface biosphere. Today we know that in many places, they invest most of their energy in simply maintaining their existence and little into growth, which is a fascinating way to live,” said Karen Lloyd of the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

“Today, too, we know that subsurface life is common. Ten years ago, we had sampled only a few sites – the kinds of places we’d expect to find life. Now, thanks to ultra-deep sampling, we know we can find them pretty much everywhere.”

The discovery raises new questions about the nature of life, and how it may have begun. It suggests that even in the worst climate catastrophe precipitated by human exploitation of fossil carbon, life would continue.

Our neighbours?

It also suggests that Earthlings may not be alone, even in the solar system: if microbes can survive deep in planet Earth, then perhaps they cling on to life under the seemingly sterile surface of Mars, or Saturn’s moon Titan, or in the ice-sealed ocean of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

There are other questions. Is life on the surface a consequence of subterranean beginnings? Or is the traffic the other way – did the deep Earth biosphere evolve from surface creatures? If their primary energy source is not solar radiation, what is it that powers them? Hydrogen? Methane? Uranium?

“Our studies of deep biosphere microbes have produced much new knowledge, but also a realisation and far greater appreciation of how much we have yet to learn about subsurface life,” said Rick Colwell of Oregon State University.

“For example, scientists do not yet know all the ways in which deep subsurface life affects surface life and vice versa. And for now, we can only marvel at the nature of the metabolisms that allow life to survive under extremely impoverished and forbidding conditions for life in deep Earth.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.