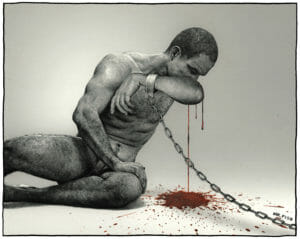

America Has Gulags in Its Own Backyard

In a groundbreaking series, journalist Shoshana Walter reveals the work camps operating all over the country under the guise of rehab centers. Find Rehab Centers / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Find Rehab Centers / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

Listen to Scheer and Walter discuss the sordid American work camps that pass for rehab centers and what regulators have failed to do—as well as what they could do in the future. You can also read a transcript of the interview below the media player and find past episodes of “Scheer Intelligence” here.

Introduction by Natasha Hakimi-Zapata

Robert Scheer: Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where I hasten to say the intelligence comes from my guests. In this case, Shoshana Walter, who’s at Reveal, the radio program of the Center for Investigative Reporting. And has, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for a great series that she did with Amy Julia Harris, “All Work. No Pay.” And it’s all about the misuse of rehab programs; we’ll get into the detail, but basically providing, if not slave labor, certainly the sort of labor denied by the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was aimed at indentured servitude and so forth. And so I want to start with this series that you did with Amy Julia Harris, who is, I gather, at the New York Times now.

Shoshana Walter: Yes.

RS: And what is terrific about it is it’s basically about good intentions gone awry, or the pretense of good intentions. In this case there’s been a movement, a good movement, to figure out an alternative to jails, to prisons. And rehab, and being serious about it. Part of it has been informed by some notion of Christian charity and religion and so forth. It’s been quite popular in the South as an alternative. And you know, it sounds good. But what your articles, this series that made you a Pulitzer Prize finalist–and the reporting was done during 2017 and somewhat into the year 2018–was basically about these judges just sending people off to a program for a year, under the penalty you’re going to be sent back to prison if you complain, or you don’t work through injury and other things. And really describing barbaric treatment of a workforce–now, we’re not talking about China, now; we get a lot of stuff about the labor force in China. We’re talking about here, Louisiana, Texas, and so forth. You’re talking about people producing items for Walmart. You’re talking about Tyson poultry, the biggest poultry in the country. You’re talking about Shell and Exxon oil companies. So, lay it out. What did you find, and you know, how did you get the story?

SW: Yeah. Well, the project began with my editor approaching me and my colleague to find an investigative story about state courts. And so what I really started doing is looking at drug courts and other types of diversion court programs that are increasingly popular now as alternatives to incarceration for drug defendants and low-level offenders. And looking at where courts were sending people for treatment, because there’s a huge treatment shortage, addiction treatment shortage in this country that’s well known. Most people who need addiction treatment can’t get it. And so that just led me to question, if there’s a treatment shortage, where are these defendants being sent? And what we found is that judges all over the country are oftentimes sending people who face very low-level charges and crimes to these long-term residential treatment programs that claim to provide rehabilitation, but in reality all they are are work camps for private companies and industries. So the first story that we did looked at a program called Christian Alcoholics and Addicts in Recovery. It’s in Jay, Oklahoma, which is a really, really rural part of Oklahoma, very close to the Missouri border. And this program was founded by a poultry industry executive who actually was having difficulty staffing her overnight shifts at this chicken plant with paid workers. So ultimately, she ended up creating her own program, and using that program to send participants to work at a series of chicken processing plants owned by Simmons Foods. And in these programs, the participants worked without pay more than 40 hours per week. They were gutting chickens, slaughtering chickens, packaging chicken parts, processing chicken meat for Walmart, KFC, Popeyes. Rachel Ray’s Nutrish pet food brand, which is an organic pet food brand that’s sold all over the country. PetSmart dog and cat food. And these participants were working without pay, for very long periods of time, in an industry that is rife with injuries, notorious for injuries. And many of them were getting very badly injured on the job.

RS: Oh, and you have some graphic accounts, ah–first of all, I mean, we should understand this is grueling work. And no wonder they were having trouble getting people to do it normally, particularly the late shifts and everything, you know.

SW: Yes.

RS: And it smells, and it’s dangerous, and tedious in every respect. And you describe scenes where someone was trying, had their glove caught in the conveyor belt, and someone tried to help them, and their hand gets mangled. And then it turns out the company doesn’t–because these are contract workers, the company doesn’t even have to provide medical or workers’ comp or any of the normal things. That’s the outfit that the judge has sent this person to.

SW: Right. That’s what makes it such a great deal for private companies. Because unlike regular employees, they don’t have to give these individuals days off or time off. They don’t have to give them holidays or sick days. They don’t have to pay overtime a lot of the time, or pay for workers’ comp insurance. These rehab programs are telling the companies, hey, we’ll take care of all of these things. We’ll make sure that you always have an employee, they’re never not going to show up, or not be on time. We’ll make sure they’re drug tested and sober. And so really, because so many of them are there under court order–they’re possibly facing years and years in prison if they don’t complete the program–they have to be there. And if they’re badly injured on the job, they end up having to stay, or face significant prison time for getting injured at work and not being able to complete the program.

RS: Yeah. So you have this disciplined workforce that can’t object to, in many cases–not all, but in most cases–what is it, not being paid.

SW: Right. In all the programs that we’ve written about so far, none of the participants are getting paid for their labor.

RS: OK, and to be clear about this, the company that has put up these workers, they provide barracks, they provide some very minimal training, they feed them. And yet if these workers complain about any aspect of it–the fact that all the money goes to the so-called rehab program–they’re going to be sent back to prison. That’s a heck of an incentive to keep your mouth shut.

SW: Exactly.

RS: And the judges–actually, what’s interesting that emerged in your articles is that the regulatory agencies and laws don’t really matter. The judges don’t really care. They don’t look into this. They think they’re doing, what, God’s work, or–you know, because sometimes there’s a big Christian aura over the whole thing, and required church attendance, required Bible study. And now go out and pluck chickens on an assembly line. And what was–I don’t want to jump to the end too quickly. But after reading all of your studies and listening to the Reveal programs–and one thing here at the Center for Investigative Reporting, and I know this because my–full disclosure, my wife Narda Zacchino, who used to be a big editor at the L.A. Times, does some work here–

SW: Yes.

RS: –you folks pride yourself on getting results, getting change, getting laws changed. Which is valid, and that’s why you win a lot of prizes. But in the case of this series that you did, despite being a Pulitzer finalist, despite–and you won the Sigma Delta Chi, the Society of Professional Journalists; you won a Knight Award, you know. And this is, by the way, for a 34-year-old; you’re in a long line of winning ever since, I guess, you got out of high school. The fact of the matter is, it doesn’t seem the laws got changed.

SW: Yeah, yeah.

RS: Or enforced, is more to the point.

SW: Right, right, right.

RS: So tell me about that. Because as recently as May of this year–this year–the health department in Louisiana spent all of two days with, I gather, two nurses who looked into this. And for two days they made some very minor adjustments, and basically said no, this is fine. This whole program where a judge sentences somebody, if you don’t want to go to prison you go here to this–and you end up working in the oil fields, or a chicken–I mean, these are rough jobs that you’re sent to.

SW: Yes, yes, yes. Yes.

RS: And so that must have been disappointing, that you–that they, what, whitewashed the whole thing?

SW: Well, rehab programs are regulated so differently from state to state. And each state has their own standards and requirements. And a common theme among all of these programs is that they tend to be unregulated. They’re not licensed, they don’t have medical staff or other aspects to their program that would typically have to fall under regulation in these states. On top of that, many of them are Christian-based or faith-based, and many Christian-based programs in the United States are eligible for licensing exemptions from state to state. They’re not required to be licensed, because they–

RS: Because they’re filing gospel?

SW: [Laughs]

RS: No, I mean, really. Is that thought to be a substitute for knowing how much you have to feed people, or medical care, or–?

SW: A lot of programs fall under those licensing exemptions. That was the case for Christian Alcoholics and Addicts in Recovery. There’s another program that we wrote about–

RS: That’s where the chicken-pluckers came from, yeah.

SW: Exactly, exactly. In North Carolina, there was a rehab founder named Jennifer Warren who founded a program called Recovery Connections Community. Prior to founding that program, she ran a different program that was licensed by the state. And she actually had her license to provide counseling revoked after she got into a sexual relationship with a client, was found to be misusing donations for personal gain, taking people’s food stamps and misusing the food stamps. So after getting kicked out of this other program, she founded a new one. When they started getting complaints about her program not following licensing requirements, a licensing investigator came out to visit, to do a site visit, and this investigator actually told Ms. Warren which–how to describe her program so that it fell outside of licensing requirements. And so as long as she described her program in a certain way, using certain language, she would not have to be licensed by the state, and therefore fall under no scrutiny for the things that she was doing with her program. And what we uncovered with that program is that she was sending people to work sometimes up to 80 hours per week at adult care homes, where they were taking care of elderly and disabled patients; they were changing diapers, bathing people, showering them, dispensing medications. A lot of participants in this rehab program ended up relapsing that way, because they had easy access to opioids that they were trying to recover from. And there were a lot of participants who also abused, sexually assaulted or abused, patients in these adult care homes. And again, they were not getting paid for any of this work. All of the pay was going to the Warrens, and they were using it for their own purposes.

RS: So let’s cut to the heart of this. Because really at the center is this word, regulation. And for a long time now, in the name of the free market, against government bureaucracy, any kind of regulation is being given a bad rap. It gets in the way of efficiency, and so whether it was–you know, Ralph Nader was the first one to challenge it, about the automobile industry: no, you can have regulations requiring seat belts, and safety codes and so forth; it actually does save lives. But generally there’s been a feeling, now, don’t get in the way of business, and don’t get in the way of good intentions. Now, there’s another assumption here. We generally have a consensus developing that our prison system, our incarceration system, is fundamentally flawed. It’s enormously expensive, it doesn’t rehabilitate people, and you got to do something. This became the quick fix. Let’s take prisoners, and what they need is a solid, you know, commitment to work and a good attitude. You know, kind of tough love. And if you’re on the assembly line plucking chickens, or out in some risky oil-rig job, you’re going to be rehabilitated. Right? And let’s not talk too much about requirements of education, or training, or skill set. And this became kind of the cop-out, right? So people sending what is basically an indentured, or slave, workforce into industry. And mind you, these are the industries that supply the chickens that you eat, and your fast food. They supply the petroleum that you’re pumping into your car. Right?

SW: Right.

RS: These are modern, high-tech, well-advertised industries with big PR staffs. And they actually give themselves awards, and other people, for their prison rehabilitation work.

SW: Yeah.

RS: And it’s basically–would you give me a summary of it? Is it basically a coercive cop-out?

SW: Well, one distinction I would make with these programs and prison labor is that a lot of people who end up getting sent to these programs by the court system have not been convicted of any crimes yet. Which is why a lot of legal experts are arguing that they are a violation of the 13th Amendment.

RS: Tell us about the 13th Amendment, because that is pretty basic to the U.S. Constitution–

SW: It’s true.

RS: –and we forget the Founders faced a situation in society where we had a lot of people who were held in the stockade or something, because oh, you violated the terms of your employment, or what have you. You know, comparable to the way we treat undocumented people now, and you know, even without a trial you’re guilty. So tell us about the 13th Amendment and how it applies to your series, because it keeps coming up.

SW: It does.

RS: Most of the lawyers that you talk to say, wait a minute, this is clearly a violation.

SW: Right, right. The 13th Amendment basically outlawed slavery in the United States. And it states that involuntary servitude is not OK, except essentially as a punishment upon conviction of a crime. And so when you have participants who are getting sent by courts to these programs, ostensibly for rehab and treatment for their addictions, what lawyers have told us is there’s an argument that that violates the 13th Amendment. Because not only sometimes are there no convictions in these cases yet, but a lot of the time, even if there are convictions, the courts are saying: this is not for punishment. This is to rehabilitate you. This is to provide treatment so that you can recover from your addictions and become a productive member of society.

RS: And the focus here, by the way, is on drug courts, where–you can make the argument these are actually victimless crimes, very often.

SW: Yes. A lot of people that I’ve talked to have been charged with marijuana possession. Or possession of pain pills, or you know, misdemeanor to felony drug offenses that increasingly are being treated by the courts as something that should not send someone to prison. But in many of these states, people are facing a lot of prison time if they don’t complete the drug court program, or they don’t complete this work-based rehab program.

RS: Yeah. And also in your article series–which, you know, “All Work. No Pay”–what was interesting is we not only have lost the notion of rehabilitation of prisoners, we’ve also lost the notion of mental healthcare. And you have some poignant stories in your series of people who really clearly needed serious mental health treatment.

SW: Yes, yes.

RS: And end up killing themselves, or having disastrous results. And there’s some–baked into this notion of tough love, which took over particularly in the South, that somehow, you know, the right stick, and combined with gospel, somehow will make you that decent person.

SW: Yes.

RS: And in fact, no, very often it makes you kill yourself. Or suffer medical injuries without proper care.

SW: Well, especially with addiction. A huge percentage of people who struggle with addiction have underlying mental health problems. So you know, with the recent story, the most recent program that we wrote about, about a program called the Cenikor Foundation. It’s been around for decades. It’s one of the longest-running and largest of these types of programs in the country. They actually claim to provide counseling in their program, but what we found is that participants were being forced to work so many hours that they really didn’t have time for counseling at all. And the program sold itself in that way, and attracted a lot of people with very serious mental health conditions. But they weren’t able to get the treatment that they needed when they were there. And this was the program that was sending people to work at Exxon, at Shell, also at Walmart. You know, they’re spending the vast majority of their time working at for-profit companies instead of getting the mental health treatment and the treatment for their addictions that they need.

RS: I think people should understand, there’s an assumption that somehow in our country we’re past these old problems of slave labor, forced labor and so forth. And between the situation of so many people who don’t have legal status–these are not people who’ve committed a crime, other than crossing the border somehow–they have no rights that are observed. So if they don’t go along, whatever their employment situation, boom, you’re out, and can be accused of a crime. But here we’re talking about people–we’re trying, there seems to be consensus, republicans, democrats–that we can’t go on incarcerating so many millions of people in this country, right? And unfortunately, some of them don’t want to do it only because it’s expensive, not just as a human rights–I shouldn’t say “just as,” not as a human rights thing. But the fact of the matter is, we’re up against maybe we don’t have non-primitive means that we’re willing to use. They require education, they require consideration, healthcare, right? And that rehabilitation may cost money. It may not be as simple as go stand on an assembly line and, you know, suck some blood out of a chicken as it goes past you. You know, and do this work, hard work, for long hours. Maybe something else is required, you know?

SW: Right.

RS: Treatment. Treatment, you know, and that takes money and effort.

SW: Yes, yes.

RS: So basically, what your series–that was the runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize; I want to stress, people who read this and judged it considered it one of the very best national stories in the country–unfortunately, I don’t think that story has changed much.

SW: Yeah. [Laughs]

RS: Well, let’s dwell on that a little bit. Because after all, as you said, you got into this to try to make things better. And I’m talking to you because I want to make things better. And is this some game we’re playing? I mean, so let’s just address that for a few minutes. Why don’t they have to respond? Why does it fall on deaf ears? Not always, but in this case.

SW: Yeah. I mean, I think what you just described is exactly right. There are a lot of people in this country who still don’t have health insurance. They still don’t have healthcare that might pay for mental health treatment, addiction treatment, counseling, methods that could actually address their addiction problems. And I think a lot of courts are ultimately relying on these programs, not even necessarily because they believe that they’ll work, but because they are low-cost or they’re free. You know, they’re not going to require courts or states to pay for them. And they are typically free or low-cost for participants, too. So if you’re someone struggling with addiction who doesn’t have financial resources, who doesn’t have healthcare or insurance, this is likely going to be your only option for rehab, is a program that requires you to do uncompensated work. And until that is addressed, this type of program is likely going to continue to exist, and courts are likely to continue to rely on them.

RS: And it’s going to continue to fail. One thing I haven’t mentioned, reading your stories, the statistics are depressing.

SW: Yeah.

RS: I mean, in one program they had an eight percent success record. What is that?

SW: Well, and eight percent, it just–that’s the rate that the program is stating that people graduate from the program.

RS: Graduate, right. Only eight percent actually get through and avoid returning to prison.

SW: They might not even avoid returning to prison. Because if you complete this program, there’s no guarantee that you’re not going to relapse, especially if you haven’t received what you needed out of the program. So even that is not necessarily an indication that the program works in terms of rehabilitation.

RS: So let’s wrap this up, in maybe too tight a little knot. But if you think of your own child–you’re listening to this, and you think, OK, your child or your nephew, or some friend, or yourself–you’ve probably gone, many people have gone to a school where they got a good education. They had a family structure that if they had psychological problems, they would get treatment. They probably had a healthcare plan or other resources to do it. In this case, looking at the people you describe in this story, most of them didn’t go to wonderful schools, and they didn’t have this family support. And you know, they were out there in an ever-tougher market for people who lack the right skills, and so forth.

SW: Right.

RS: So they are caught, or charged, with committing a crime. Some of these people didn’t even have a trial. And some judge, who thinks he’s doing the right thing, or she thinks she’s doing the right thing, says well, why do I just want to lock this person up? They’ll come out worse; I know the prison system. Why don’t we, with the grace of God and gospel–and there’s a little bit of Christian overlay, which is true of many of these programs–try to get this person a second chance by plucking chickens on an assembly line, right? For grueling, hard work, but it’s better than being in prison. A number of the people you quote in this series say, no, it wasn’t better. You know.

SW: Right. I mean, I think–I will say–

RS: And–so–just to put the finest point on it, this is kind of a hoax of we’re going to do it a better way, when actually you’re doing it in a way that’s doomed to failure. So the next turn of the screw will be, oh no, lock ‘em up. Stiffer sentences. We tried reform and it didn’t work. No, you didn’t try reform. You tried a charade of reform. That’s really what your series exposed.

SW: Yeah.

RS: And then the saddest thing–correct me if I’m wrong–despite your being a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and winning the Knight Award and the Society of Professional Journalists award, so your series was honored–sadly enough, they didn’t have to do anything about it, the people running these programs. They could blow you off.

SW: Yeah. I mean, you know, there have been some positive changes that have come out of the series. There’s a number of criminal and regulatory investigations that remain ongoing. There are, I believe 10, up close to 10 federal class-action lawsuits currently ongoing. Participants are suing these programs for back wages, and many of the complaints allege human trafficking, 13th Amendment violations, and violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act. So those are still ongoing. There were a number of courts that did stop sending people to these programs. And of course, many, many people who have stopped sending their loved ones to these programs. And I will say that there are people who will claim that they were helped by these programs. And I think that is true; I think there is a very small minority of people who do seem to find recovery in these programs. But it’s a very, very small minority. And I think in terms of courts sending people to these programs, because we don’t have a system of addiction care set up that helps objectively evaluate people who need treatment, to determine what might be the best treatment for them, it’s kind of a trial and error approach. And people who are going into programs voluntarily, they have the luxury of trial and error to an extent; if they have family resources and some form of stability, they can try many different approaches until they find something that works. But people in the criminal justice system don’t have that luxury. They’re often given one option or nothing at all, and oftentimes that option does not work for them. And I think that’s just going to continue to be the case, because still for the vast majority of people struggling with addiction, it’s prison, it’s incarceration of some kind. And for those who get another opportunity, it likely is not going to work for them.

RS: Yeah. But when I say doomed to failure–and I recommend people read this series–if you want to give people a shot at normal life when they’re plucking these chickens, pay ‘em. That would be one good thing, you start to get some cash income. Don’t just pay the people who’ve turned you over, you know, and then you got to go back to basically what is a form of prison, wait for the next day’s work. Give them some rewards, show them that work gives some advantage. So I think you’ve really described a system designed to fail. However, I like your optimism at the end. The series is called “All Work. No Pay.” And the reason I’m doing this podcast is not to increase cynicism. I feel optimistic; here we have a 34-year-old reporter who’s winning all these prizes and doing great work. And I think people have got to–this is a second chance. That’s why I do these podcasts. Try to get people, you know, to read it and act on it. You know, find out. And even–you know, it’s not just Louisiana or Florida. After all, these marijuana camps are in California, if you think you live in such an enlightened state, in the big, deep blue. You know, see what they’re doing with their prisons. What happens in New York State? In Illinois? So what I’m trying to do is get people to actually revisit this work. This is terrific journalism. We’ll post it and so forth, so people get the whole collection. “All Work. No Pay.” And I want to thank you for being here.

SW: Thank you so much for having me, Bob.

RS: And continue to follow the work of Shoshana Walter. I want to thank Mario Diaz and Kat Yore, our engineers at KCRW. Joshua Scheer is the producer of Scheer Intelligence. And here at CIR Reveal, we have Mwende Hinojosa. Is that right? You tell me.

SW: Hinojosa.

RS: Hinojosa, who’s been really patient with us. And I think we took a little extra time here, but I think it’s well worth it. These kind of stories should not just be for prizes. What you want to see is the prize in–if this was good enough for the Pulitzer committee, why haven’t you read this story or listened to the Reveal series based on it? How do they get Reveal, how do they get CIR, if they get motivated by this?

SW: Go to RevealNews.org, or you can tune into NPR, your local NPR station or find our podcast on iTunes or wherever you get your podcasts.

RS: Right. And you can do it even on the station that you’re listening to this on, on KCRW, which had that show, so to be applauded. Check it out. See you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.